Ten Days to Kamikaze is a series that explores the decision-making process and implementation of Japan’s use of suicidal crash dives during World War II. It provides an in-depth review of the critical ten-day period and examines the background leading up to those decisions. On Y-Day, as Japanese surface forces close in on Leyte, the Japanese Army’s 2nd Flying Division and Navy’s 2nd Air Fleet mount maximum efforts with conventional attacks. Their success or failure will weigh on the decision of how extensively crash tactics will be use.

If you are just joining the series, you can read previous posts here:

Ten Days to Kamikaze – Part II

Ten Days to Kamikaze – Part III

Ten Days to Kamikaze – Part IV

Ten Days to Kamikaze – Part VI

Now on to Part VII!

October 24 – Full scale attack

This was Y-Day last day before the decisive battle (X-Day) of Sho-1. The Japanese surface units used the day for the final approach through close-in seas and straits of the Philippines. Along two axes forces containing battleships, cruisers and destroyers planned to debouche north and south of Leyte just after midnight. Their intent for the 25th was to sink or drive away any opposing warships and then destroy shipping in Leyte Gulf leaving the Americans ashore without support or sustenance. The original plan was to destroy the landing force before ground troops could get a foothold ashore. It was too late for that, but the possibility remained of leaving the American troops isolated and under- or unsupplied just as Japanese ground forces had been at Guadalcanal. Cruiser Myoko launched a seaplane that reconnoitered the Leyte anchorage just after dawn to give surface forces a complete picture of American dispositions. The intruder was not intercepted or detected by radar.

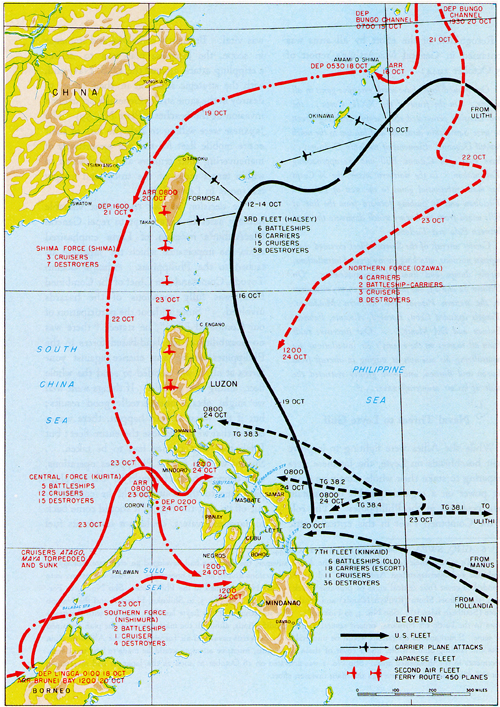

Movements leading to the decisive battle.

Admiral Ozawa’s force was not successful in its decoy mission on the 24th although it was sighted and would be on the following day. A group of American carriers was located east of Manila (TG 38.3) and two other groups farther south off the central Philippines. Halsey’s carriers sent successive strike waves amounting to over 250 aircraft against the advancing Japanese ships. The ineffectiveness of Japanese ASW operations the previous day was mirrored by failed air cover. The Japanese sent some fighters to protect their surface forces, but they were driven away by ‘friendly’ AA fire. The ships’ floatplanes could do little against the attackers.Throughout the day the Japanese surface forces basically had no air cover. Carrier planes sank modern battleship Musashi, heavy cruiser Chokai, and a destroyer. Another heavy cruiser was heavily damaged and turned back. Other ships were damaged to a lesser extent. The attackers suffered the loss of thirty planes due to combat or operational causes.

The escort carrier air groups did not take part in attacks on the Japanese fleet but beefed up combat air patrols to thirty-six fighters with sixteen additional fighters on ten-minute standby. They had 310 fighters and 188 TBMs on board. Most strike missions were cancelled but fighter sweeps and one strike of forty-four aircraft were sent against Japanese airfields in the Visayas in the middle of the day. Several planes were claimed destroyed on the ground. The commander of the 19th FR Maj. Rokuro Seto was killed during this bombing attack on Negros Island.

Kamikaze operations were a bust. The concentration of three units on Mindanao appeared to be misguided. One of two search planes sent out from Davao failed to return. No targets were sighted, and the Zeros remained on the ground. Later Shikishima and Yamato units reportedly went out on missions that returned without having found targets to attack. This left it up to the conventional attack forces of the army and navy to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Lt. (j.g.) Kenneth Hipp scored his only air victories against Army attack aircraft.

For the 4th Air Army Tominaga stated his expectation was for his pilots to sink or disable a hundred ships in the first two days of all out attacks. This was wildly and unreasonably optimistic. In earlier attacks single planes and small formations had used terrain and environmental conditions to execute attacks with reasonable losses and with overstated but believable results. Attacks by bombers carrying heavier bombs should enhance results. However, mass attacks approaching at altitude would sacrifice the avoidance of radar early warning that had limited losses in earlier attacks. If Tominaga believed his exhortation or something close to it was within the realm of possibility it might partially explain why he had taken no action to organize army special attack units.

Tominaga’s message may well have been heard and taken to heart. Attacking Japanese bomber pilots attacked with courage and determination during the day. The first wave of attackers was heavy with bombers. The relatively thin fighter escort failed to match the bombers in determination; neither was tactical skill prominently displayed. The first interception of the day did not occur over Leyte Gulf but far to the west between Negros and Cebu Islands.

The 2nd Flying Division Attacks

Eight Type 99 assault bombers of the 65th FR led by regimental commander Capt. Kitamura took off from Bacolod, picked up a fighter escort over Fabrica and headed for Leyte Gulf. At 0730 twenty-five miles east of Fabrica the formation encountered a search/attack group from U.S.S. Franklin consisting of eight Hellcats and six Helldivers. The Americans reported their opponents as twelve Vals and five Oscars. Cdr. Wilson Coleman of VF-13 led his division of Hellcats against the Japanese formation while the rest of the planes stood by to carry out their assigned mission. Combat took place in and out of clouds. Coleman claimed two Vals and his wingman Ens. Frederick Griffin claimed a third; two others were claimed as probables. The American attack group reformed to continue its mission. The Americans reported that the Japanese fighters were a non-factor neither effectively intervening as escorts nor attacking the planes of the strike group. The delay caused by the combat possibly contributed to their failure to find any Japanese ships and return to Franklin without attacking. A second similarly constituted strike group from Franklin sank a destroyer in a reinforcement convoy and reported the position of one of the Japanese attack forces.

Meanwhile Kitamura and his wingman Cpl. Itaba escaped the Hellcats, joined up and continued to Leyte Gulf. There they reported attacking a destroyer. Each claimed hits that started a fire. One wing of Itaba’s Sonia was badly damaged by anti-aircraft fire and Kitamura’s plane received slight damage. They returned to the unit’s main base at Lipa on Luzon. Their bombs were near misses on destroyer U.S.S. Leutze; one within ten yards the other fifty yards. The ship suffered minor damage and eleven crewmen wounded most only slightly. Leutze reported hits with AA fire and claimed one Val probably destroyed with a portion of its wing shot away. The “fire” the Japanese pilots reported might have been smoke and flashes from Leutze’s five-inch, 40mm and 20mm AA fire. Later in separate incidents Leutze and other ships fired on two other “Vals” over the anchorage. There were no reports of damage associated with their incursions.

The first mission from Luzon was an early morning fighter sweep by Type 4 fighters of the 51st and 52nd FRs flying from Del Carmen. They reached Leyte encountered no air opposition, strafed U.S. ground positions and withdrew to Saravia. Sixteen Type 4 fighters of the 16th FB were assigned to escort the Type 99 light bombers of the 3rd FR. They failed to rendezvous with their charges and flew on to Leyte, later alleging the bombers were late arriving at the rendezvous. They apparently arrived over Leyte in somewhat disorganized fashion and likely were among the fighters Americans identified as Zekes, Oscars or just as single engine fighters in various combats. Six pilots of the 1st FR were lost. Meanwhile separate formations of twin-engine light and heavy bombers made their way south from Luzon. A double strength CAP of thirty-six fighters was aloft, and they were soon joined by additional fighters totaling around fifty.

The first bombers to approach Leyte that morning were probably from Lt. Col. Shuichi Kimura’s 3rd FR. The unit was equipped with the Type 99 light bomber model IIB (Ki 48) an aircraft of modest capabilities, but much used by the Japanese Army Air Force in China, Burma and the Pacific. The unit had a nominal strength of thirty-six bombers (twenty-seven initial equipment and nine reserve). It transferred from Okinawa to the Philippines after the Leyte landings with twenty-nine aircraft. While at Okinawa the unit trained in skip bombing. On this day each aircraft carried a single 250kg bomb for that purpose. During skip bombing training an aircraft and its crew had been lost. Given what was to unfold during the day and more particularly on the following day it is ironic that crews nicknamed skip bombing training Tai-Atari Enshu (suicide maneuvers). According to a survivor twenty-four bombers took off for the mission. They flew in a V or arrowhead formation of three squadrons (chutai): the 1st chutai with nine flew in a V of three plane V’s; the 2nd chutai likewise but with one V-element missing an aircraft, and the 3rd chutai in a single V formation of seven aircraft.

Sorting out what happened between two Japanese bomber formations, various Japanese fighters and numerous separate formations of intercepting American fighters, given aircraft misidentifications and clearly erroneous reports of time of interception, results in only partial clarity of events. The action may have begun with four Wildcats of VC-27 sighting four fighters identified as Oscars a few thousand feet above them. Upon reaching their altitude the Oscars (possibly Type 4 Franks) avoided combat and outran the Wildcats. The Wildcats, however, sighted Japanese twin-engine bombers that they identified in their combat report as Frances. Lt. (j.g.) Frank Leighty along with his wingman initiated an attack that sent a bomber crashing into the ground on Leyte, the only combat report to specifically mention a crash on the ground. Flying in the 2nd chutai of the 3rd FR formation was a bomber flown by Sgt. Fujio Yasuma. The first fighter pass flamed its left wing tank. A second pass hit Yasuma in the head. The Lily fell in an uncontrolled dive and smashed into the ground. The front half of the aircraft crumpled in flaming wreckage. The crew except for the flight engineer/gunner was killed. The survivor Cpl. Seikichiro Enomoto was thrown from the aircraft and though suffering burns, survived to tell the story of the first part of 3rd FR’s mission as a prisoner of war. Leighty claimed two additional bombers and the rest of his flight added three others. Flights from several squadrons assailed the Japanese bombers that held formation and steepened their glide from 9,000 feet toward the ships. Bomber after bomber fell in flames. Little return fire was noted but one Wildcat was hit and crashed on Tacloban airfield.

Another Wildcat Pilot Lt. Kenneth Hippe of VC-3 in his first and only air combat sighted twenty-one Lilys and noted their V of V formation. After shooting down one bomber in an overhead gunnery run he followed the formation as it picked up speed in its glide toward the ships. He fired on bombers from a tail position and claimed four additional Lilys. His three VC-3 flight companions claimed another seven. Other squadrons also engaged. Total claims were for twenty Lilys. If all the Frances claims were Lilys total claims totaled twenty-six. Japanese data indicates twenty failed to return, two force landed (crashed) badly damaged and two returned badly damaged also likely write-offs. Not all of those failing to return were wholly the result of fighter action. A few bombers got into the zone of ships’ AA fire and fighters broke off the action; their fate is described below.

Fighters were directed to another formation approaching from the northwest which headed down San Juanico Strait between Samar and Leyte. This formation consisted of successive flights of four bombers in rough line abreast. By one count there were thirty-two bombers identified as Sallys. Most of these must have been from the 14th FR that arrived in the Philippines with twenty-five Type 97 heavy bombers two days earlier. The successive four plane flights were separated such that intercepting fighters could attack between enemy flights. The few Japanese fighters that attempted to cover these bombers were largely ineffective. Lt. Cdr. Harold Funk, commander of VF-26, was the leading light in this interception claiming four Sallys and a fighter in his FM-2 Wildcat. In another mission later in the day he claimed a sixth victim. The squadrons involved claimed a total of eighteen Sallys.

As the Lilys came into sight of the Liberty ships and landing craft close ashore east of Leyte observers in the LST group saw about fifteen bombers. Four were seen shot down by fighters and four were believed to have fallen to AA fire. One bomber crashed close to the bow of Liberty ship David Dudley Field. Another clipped the Field’s No. 7 gun tub lost a wing and crashed nearby. LCI-65 took a bomber under fire that hit the ship’s stern as it crashed. Fires broke out and though damage was relatively severe casualties were light. LCI-1065 was not so lucky; a bomber crashed aboard. The ship was engulfed in flames and quickly sank with crew casualties. The Liberty ship Augustus F. Thomas was alongside 1,400-ton ocean going tug U.S.S. Sonoma transferring supplies when a Japanese bomber, identified as a Betty in some reports, approached. The bomber struck the Sonoma, its bomb apparently penetrated Thomas’ hull and it crashed between the two ships. Thomas with 548 personnel, 3,000 tons of ammunition and 1,000 tons of gasoline aboard was disabled with a flooded engine room. The ships suffered about 200 casualties. Sonoma which had a distinguished record participating in SWPA amphibious operations was beached but subsequently sank. Thomas remained afloat and after various vicissitudes was beached. She ultimately survived. Transport U.S.S. Fremont was reportedly hit with a single shell, but seven crewmen were injured.

What role the Japanese heavy bombers played in the damage to shipping is unclear. Some of their bombs apparently fell on shore. Shore based AA reported a dozen bombers attacked in four raids during the day with four claimed shot down and others damaged or probably destroyed. The Red alert for this series of raids was sounded before 0800 and attacks commenced by 0820. Most Japanese planes had cleared the area by 0900 and the “White” all clear was sent at 0930. The U.S. fighters claimed over forty victories and lost three of their number. The 2nd Flying Division post-strike message says eighty planes took part in this first phase of the first day of the “all out” attack.

The second phase attack resulted in a Red alert at 1113 and all clear at 1341. This and the third phase later in the day were apparently heavily weighted in fighters and fighter-bombers. However, the Type 99 assault bombers of the 6th FB were back. Two were escorted by three fighters. A quartet of VC-80 Wildcats sighted three fighters about 1130 and chased them across Leyte eventually claiming two Oscars destroyed. Meanwhile the assault bombers attacked. W.O. Masao Ida of the 66th FR reported he scored a hit on a 6,000 ton ship with the one 100kg bomb his plane carried at 1143. He later had a run in with Grumman fighters but escaped by diving to low level and using cloud cover. American reports verify Japanese aircraft, estimated at up to forty in number, in the area with AA and fighter action. Ten Zekes were reported in what the American fighter controller designated as Raid No. 1 of this phase. However, no damage is ascribed to attacks in this phase. The 2nd Flying Division report stated thirty-eight planes were involved.

It was after 1700 hours when the third phase attack resulted in a Red alert, but U.S. reports verify few combats and no damage. The initial claim was for a Zeke, later a couple claims for Vals and finally a claim for an Irving. These identifications were for navy aircraft that were not involved! The Japanese reported twenty-nine planes in this phase. The 2nd Flying Division sent out a message summarizing the day’s action which stated 147 planes attacked and 47 were lost. Damage claimed was one cruiser and one landing craft sunk; five transports set ablaze; and two cruisers damaged. The message made no note that most damage was inflicted by crash dives. American aerial claims for sixty-six aircraft destroyed where only modestly exaggerated by World War II mass combat standards. Another twenty or so claims were for probable victories. However, as noted above not all Japanese losses were the result of fighter action. American fighter claims may have been about 60% accurate.

Despite its losses during the day, including losses to planes transiting from Formosa to the Philippines, 2nd FD ended the day with more planes operational than at the start of the day. By the following morning 180 planes were available. In assessing the contributions of the 2nd FD it should be noted that the air groups of the escort carriers played no role in harassing or inflicting damage on the advancing Japanese surface forces. They played only a minor role in attacking Japanese air bases from which additional attacks could be launched on the morrow. Had it not been for the massive American superiority in aircraft of Halsey’s force (and their failure to find and attack Ozawa’s decoy force) the day might have been quite different.

Combat for the day was not finished at Leyte Gulf. Although the Japanese navy dedicated most of its efforts against Task Group 38.3 during the day, Halsey’s carriers farther south caused the most damage to Japanese surface forces. A Japanese navy mission approached Leyte Gulf as the sun faded into darkness; it was probably seeking carriers operating east of San Bernardino Strait. Four bombers came out of the darkness to drop torpedoes. In addition to close calls one hit the fleet oiler U.S.S. Ashtabula opening a 24×34-foot hole on her port side. Despite the gaping hole and distortion to bulkheads there were no casualties and no damage to vital mechanical systems. She took on a 12-degree list but continued to navigate. She stayed in the combat area a couple days until finally withdrawing for an extended period of repairs. Many months later she returned to service and had a long post-war career. The only reported damage ashore also came after dark. Bombs set an ammunition dump ablaze.

Japanese army attacks on the Leyte Gulf shipping inflicted some damage. Attacks were costly and not particularly significant in terms of the vast array of potential ship targets. The 2nd FD was prepared to renew the attack the next day and in the days to come. Incremental damage could be inflicted on the ships providing troops and supplies to the invading Leyte ground forces. For the Japanese navy, the situation was different. The 24th was Y-day, the day before the decisive naval engagements that would be the culmination of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The line of communications and vital source of supply in Japan’s southern “resource area” was at stake. This was a battle that might be the last before the home islands came under direct attack.

Attack On Task Force 38

Admiral Fukudome made the fateful decision to marshal his air power resources in attacks on the American carriers rather than provide fighter cover for the various Japanese surface forces approaching Leyte Gulf. Having done so he began the search for carriers early, beginning late on the 23rd. It was fifteen minutes before midnight when American radar picked up a bogey. The intruder a Type 2 large flying boat (Emily) of Air Group 901 was equipped with radar. This was recorded as Raid No. 1 and by 0029 it was within 26 miles of Task Group 38.3. Light cruiser U.S.S. Birmingham was directed to jam its radar. However, a sighting report had already been sent and by 0050 was received and decoded at Fukudome’s headquarters. The intruder later faded from radar and was eventually picked up by radar from TG 38.2 to the south. The Emily was shot down by night fighters from Independence at 0229. An hour or so later Independence night fighters claimed a Mavis flying boat. By about 0530 TG 38.3 was tracking four separate bogies.

At 0611 TG 38.3 launched CAP fighters from light carriers Langley and Princeton. Within barely half an hour they were in action. They claimed their first kill of the day – identified as a Nick. Air Group 141 operated reconnaissance planes/night fighters (including the twin-engine Gekko or Irving) but not the somewhat similar army Type 2 two-seat (Nick) fighters. Of three Irvings sent out as part of the early morning search only one returned to base. In the next half hour CAP fighters claimed another Nick, a floatplane, and a Frances (likely a Ginga of K406). The number of “raids” showing up on radar typically just a single aircraft reached ten over the next hour or so. Meanwhile TG 38.3 launched a fighter sweep to the Manila area and search/strike missions to the Sibuyan Sea, Manila Bay and other suspected locations of Japanese surface forces.

Prior to arriving in the Philippines Sixth Base Air Force was organized into tactical formations for operations there. The night and early morning reconnaissance missions encountered by TG 38.3 reflected that organizational plan. Twin-engine bombers on patrol and seaplanes on anti-sub missions were also operating according to the pre-set organization. The fighter and attack elements anticipated in the organizational plan had been much reduced in number due to operational losses and American attacks. New Shiden interceptors which may have been intended primarily for air defense were pressed into service as escort fighters.

Suisei dive bombers ready to take-off.

Ace David MacCampbell in his Hellcat.

Radar operators noted that Japanese formations seemed to be wandering aimlessly and milling around. The Japanese attack was frustrated by low clouds and squalls that protected the carriers. Weather protected the ships for the most part of an hour before squalls dispersed and clouds formed in layers at various altitudes. Three divisions of Hellcats from Langley and Princeton stalked the Japanese intruders as forty-two other Hellcats rose from carrier decks to join them. The Japanese formations that the Hellcats engaged included a fighter sweep of twenty-six Zeros and the main attack formation of bombers, Zeros and Shidens.

Princeton Hellcats engaged in a series of dog fights that resulted in claims for 36 victories. Ensign Thomas Conroy claimed six victories and four other pilots claimed five kills each. One Princeton Hellcat failed to return; four Hellcats were badly shot up with one pilot wounded. Lt. (j.g.) John Montapert of Langley’s CAP had already shot down a Kate in an earlier interception when his division engaged Japanese fighters the majority of which were identified as Zekes but with others identified as Tonys and a Tojo (none of these two types were present). He claimed three Zekes. In addition to the CAP flight’s six victories VF-44 upped its score by another twenty kills later in the day. According to Montapert’s combat report: “Tony and Tojo will not readily explode, burning a short time after being hit and the fire going out.” Despite various pilot reports, the TG 38.3 action report makes no mention of claims for Tonys, Tojos or Hamps. These were apparently the basis for reporting victory claims for 28 “unidentified” aircraft. Presumably intelligence officers knew what they weren’t but not what they were.

A partial explanation for Montapert’s observation may be that his division encountered unfamiliar Shidens which were well protected with armor and self-sealing fuel tanks. Despite their protective features eleven of 21 Shidens of Air Group 341 failed to return from the mission; some probably due to operational causes. Additionally, Zekes that were encountered had various levels of fuel tank protection. The original version of the Zero 52 in production from August to December 1943 had no fuel tank protection. Zeros coming off the Mitsubishi production line in late 1943 and early 1944 had an automatic CO2 system to protect the wing tanks. Nakajima Zeros 52’s produced from early 1944 also had a similar CO2 system. Unlike American CO2 systems this did not purge the tank interior to prevent fire but sent CO2 over the external surfaces of the tank when the heat of fire initiated the system. This is like spraying firefighting foam on to a fire. Under optimal conditions this would extinguish a fire. Zeros coming off the production line after June 1944 had an automatic CO2 system protecting the fuselage fuel tank as well as the wing tanks. Evidence suggests use of the unprotected tank in front of the pilot had been discontinued.

The Langley and Princeton Hellcats were soon joined by reinforcements from their own carriers (twelve each) as well as from Lexington (11) and Essex (7). Hellcats engaged the fighter sweep Zeros of Air Group 221 which lost eleven fighters including Lt. Cdr. Minoru Kobayashi hikotai leader of S317. The Zeros claimed six certain victories and one uncertain. The main formation of fifty Zeros from various units lost at least nine while claiming eleven sure victories. Hellcats of various squadrons clashed with the main attack formation. The formation broke up under attack. VF-19 from Lexington got among the bombers and claimed seven of nine Vals they encountered as well as three Jills, two Zekes and an aircraft identified as a Nick.

Due to one pilot failing to take off and communications problems the two Essex Hellcat divisions numbered seven fighters instead of eight and were in flights of two and five. As the Essex Hellcats made contact the Japanese formation reversed course resulting in some Japanese planes stringing out and straggling. Commander McCampbell ordered the five plane flight to attack the stragglers while he and Lt. (j.g.) Roy W. Rushing climbed for altitude to work over the Japanese from top down. According to McCampbell’s combat report:

The attack by the two components of my flight commenced almost simultaneously, which action caused the “Hawks” and “Fish” [dive bombers and torpedo planes] to dive down through the overcast…After we had made 3 or 4 passes, the “Rats” [fighters] having lost sight of their escort, commenced to orbit in a large orderly and well formed “Luffberry” , during which my wingman and I were unable to find an opening in order to attack…we decided to maintain our altitude advantage and await their departure, as a result of which there was bound to be confusion and “easy pickings” amongst the stragglers. There were: During the next hour or so we followed the formation of weaving fighters, taking advantage of every opportunity to knock down those who: (1) attempted to climb up to our altitude, (2) scissored outside of support from others, (3) straggled, and (4) became too eager and came up to us singly. In all we made 18 to 20 passes, being very careful not to expose ourselves and to conserve ammunition by withholding our fire until within very close range…After half an hour a third pilot Lt. (j.g.) Black joined us we were able to attack larger formations and on 1 or 2 passes I remember we flamed three at a time…Zekes predominated with a few Oscars and Hamps. Most of these fighters carried what appeared to be a 550-lb. bomb either on the right stub wing or under the belly. The E/A remained in one large loosely formed group (excepting the flamers) as they proceeded toward Manila…My claim of 9 planes includes only those seen by my wingman and myself to flame or explode.

Accounts with additional detail note that McCampbell carried out a couple head on passes against Japanese fighters while they were in the Lufbery. Neither was successful and McCampbell’s fighter took hits. Thereafter he decided on the “easy pickings” approach. Using dive, fire and climb tactics McCampbell could note damage in the form of flames and explosions. None of the victims of McCampbell’s victory claims bailed out nor was “seen to crash” the basis of his claims. There are no details that “explosions” resulted in aircraft structures critical to flight coming off the aircraft attacked. In addition to fifteen victories McCampbell and Rushing claimed several other aircraft as probably destroyed or damaged. McCampbell’s victories included five Zekes, two Oscars, and two Hamps (no Oscars or Hamps were involved). McCampbell’s tactics were intelligent: easy pickings and limited exposure to enemy counterattack. However, the tactics were not conducive to extended or detailed observation of the fate of the victims of attack. The misidentification of his victims further illustrates what he thought he saw and what occurred were not necessarily the same. We cannot know how many, if any, of his claims were valid in the sense that an enemy aircraft was destroyed. From his description quoted above however, it is not evident that any of his victories met the official standards for kill verification that had been promulgated many months earlier.

The seven Essex Hellcats claimed a total of 25 victories including some bombers. Rushing achieved ace-in–a-day status by claiming six. Like many of the other CAP Hellcats they chased the Japanese most of the way back to Luzon. Reaching Luzon did not necessarily mean safety for Japanese aircraft. It appears some of the Japanese aircraft returning from the mission fell victim to aircraft from other task groups homeward bound from strike missions. The aggressive pursuit of retreating Japanese aircraft while rich in victory claims also had less positive consequences.

With most CAP fighters having flown many miles from the task group several Japanese strike aircraft lurked in the vicinity of the carriers using cloud cover to avoid interception while seeking breaks in the clouds to find targets. A follow up wave of ten unescorted Suisei dive bombers approached without being intercepted. More than an hour after the mass Japanese formations were intercepted a single Suisei dove through thin layers of cloud to place a 250kg on Princeton’s flight deck. A single 250kg hit could cause significant damage but would not normally sink a CVL. This bomb penetrated the flight deck, penetrated the hanger deck, and exploded beneath it. On the hanger deck six torpedo armed, fully fueled TBM’s were enveloped in flames. They had been sent to the hanger deck to clear the flight deck for returning CAP fighters several of which had landed. Catastrophe after catastrophe befell Princeton. Stored torpedoes exploded. Fires ravaged the ship. In addition to the damage suffered by Princeton light, cruiser Birmingham was damaged and suffered hundreds of crew casualties trying to aid Princeton. Three assisting destroyers were also damaged by debris from explosions on Princeton. Many hours later burned out and adrift she was sunk by torpedoes from a U.S. destroyer.

U.S.S. Princeton devastated by a 250 kg bomb from a Suisei dive bomber.

[1] One hundred-fifty-eight is the figure given by Bates Vol. IV (Part I, note 1) based on captured documents available to his research team. The figure given in Japanese Monograph No. 84 (Part I, note 1) is 189, 126 fighters and 63 attack aircraft.

[2] Total claims by TG 38.3 fighters including those against Ozawa’s carrier plane attacks were 162.

[3] Compare footnote 2, Part II, regarding the Leyte landing, MacArthur to Halsey “your mission to cover this operation is essential and paramount.”