Ten Days to Kamikaze is a series that explores the decision-making process and implementation of Japan’s use of suicidal crash dives during World War II. It provides an in-depth review of the critical ten-day period and examines the background leading up to those decisions. In the midst of escalating tensions and growing doubts surrounding Tokyo’s claims of decimating American aircraft carriers, a startling revelation strikes senior Japanese leaders on October 16-18: the Americans persist as an indomitable force.

If you are just joining the series, you can read previous posts here:

Ten Days to Kamikaze – Part II

Ten Days to Kamikaze – Part III

Now on to Part IV!

October 16. Monday the sixteenth saw the final Japanese attacks on ships escorting cruisers Canberra and Houston which Japanese aerial torpedoes had crippled off Formosa. No damage was inflicted but several Japanese planes were lost. There were no other important combat operations. The task forces of Halsey’s Third Fleet were fueling and moving to new operational areas. Lead elements of the U.S. Seventh Fleet were approaching the Philippines to position themselves for preliminary landings scheduled for the following day. Many ships found themselves transiting an inter-tropical depression, the outer edges of a typhoon. This made the passage extremely uncomfortable for troops and crew aboard ship. Despite difficult conditions the escort carrier force refueled. The storm also shielded the ships from possible discovery by the Japanese. One small vessel a motor minesweeper (YMS-70) sank, and other ships suffered minor storm damage. The nearest ships approached within 150 miles east of Mindanao during the day. The same weather system inundated Japanese facilities south of Luzon rendering some airfields temporarily unusable.

Task Group 38.4 received replacement aircraft and air crews from CVE Sitkoh Bay during the day. In addition to seventeen pilots and fourteen crewmen the carriers brought aboard eighteen fighters and four Avengers to partially replace recent losses. Each carrier received one torpedo plane. Eight of the F6F-3 Hellcats went to the flagship “Big Ben” Franklin.

For the next few days carrier aircraft hit targets on Luzon and farther south in the Visayas. U.S. Far East Air Force fighters and bombers were covering Mindanao as well as targets in Borneo and the Netherlands East Indies. P-38s strafing ground targets on Mindanao came across a twin-engine bomber identified as a Sally on Cagayan airfield and left it in flames.

C-in-C Combined Fleet Admiral Toyoda felt it prudent to move with his advanced headquarters from Shinchiku in the north of Formosa to Takao so he could be in direct contact with commander Sixth Base Air Force. This allowed him to keep his surface forces fully apprised of aerial search information without potential communications delay or disruption. It also allowed him to better coordinate air and surface operations that seemed to be in the offing. For the previous few days V-Adm. Onishi had been with Combined Fleet headquarters at Shinchiku and traveled with Admiral Toyoda to Takao. Onishi’s appointment as commander 1st Air Fleet had been announced October second. Having been most recently assigned to the Munitions Ministry he may have wanted time to fully acquaint himself with the operational situation before assuming his new command.

During the day an interesting accumulation of data was presented to Japanese naval leaders at Takao. Messages from search planes reported sightings of several American aircraft carriers which seemed undamaged. Late in the day Toyoda was apprised of two announcements emanating from Imperial General Headquarters. One was a composite report of damage inflicted upon attacking American carrier groups from Formosa over the last few days. It claimed as sunk eleven carriers, two battleships, three cruisers and a destroyer with other ships of various types, including six carriers, damaged. The second report related to Japanese attacks from Luzon the previous day. It claimed one carrier sunk, three carriers damaged and one battleship or cruiser damaged. Based on sighting reports Toyoda must have concluded that the Tokyo communiques were essentially positive ‘spin’ or propaganda that gave full credence to combat reports of dubious reliability and even enhanced them. He no doubt realized he continued to face strong American forces that had suffered only limited damage. Onishi at Takao was an interested observer absorbing information, assessing, and considering how it impacted the command he was about to assume.

Japanese claims of ships sunk resulted in a tongue in cheek Navy Department press release from Hawaii two days later:

Admiral C. W. Nimitz, U. S. Navy, Commander in Chief, U. S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, has received from Admiral W. F. Halsey, Jr., U. S. Navy, Commander, Third Fleet, the comforting assurance that he is now retiring toward the enemy following the salvage of all the Third Fleet ships recently reported sunk by Radio Tokyo.

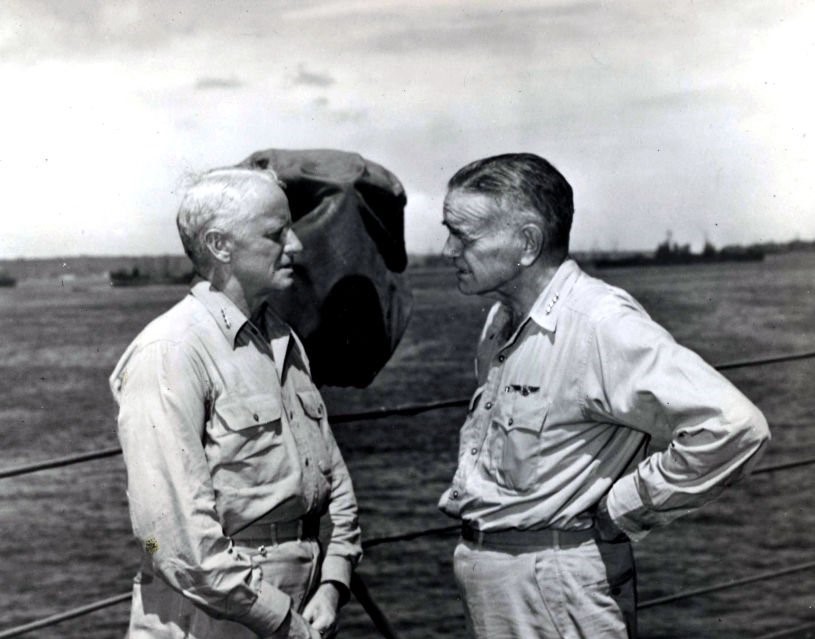

Admirals Nimitz and Halsey

Halsey was in fact considering the possibility of a fleet action against Japan’s Mobile Force, the last of its carriers and their reduced air groups. As tensions grew that force had yet to sortie from Japan. In the meantime, Halsey’s carriers had less exciting but important work to do in the Philippines. Also headed toward the Philippines aboard ship was General Douglas MacArthur.

October 17. In the predawn hours the first elements of the invasion fleet approached Leyte Gulf. Assault troops, primarily Army Rangers landed on Suluan and Dinagat Islands. Due to adverse conditions the planned landing on Homonhom I. was postponed to the following day. Minesweeping teams were on hand, but weather limited their operations. Japanese naval lookouts got out a radio report before 0730. They also destroyed secret documents including sought after charts of minefields before American commandos could secure them. Japanese opposition on land and sea was weak.

The escort carriers of the Seventh Fleet backtracked in stormy conditions and did not get into action during the day. Only the carriers of Admiral Davison’s TG 38.4 were active against the Philippines. They started before dawn with four F6F-5(N) night fighters heckling Legaspi airfield in southern Luzon. Next came a fighter sweep over the Clark airfields by twenty Hellcats. This flushed an “aggressive” response by an estimated forty fighters. In the resulting combat American claims for nine Tonys, six Oscars and five Zekes. This was followed by a strike by sixteen Hellcats, nineteen Helldivers, and fifteen Avengers. Nine air kills were claimed, and thirty to forty planes were assessed probably destroyed or damaged on the ground. Four planes, two pilots and two crewmen were lost. Japanese air and ground losses including both destroyed and damaged amounted to twenty aircraft. Shortly thereafter a similar strike against Legaspi met no aerial opposition. Installations on the ground were hit. While these strikes were taking place CAP Hellcats claimed two twin-engine aircraft some miles from the task group in early and midmorning. These may have been the Ginga (Frances) from Clark, one of four, and the Type 1 land attack bomber (Betty) lost on search missions during the day.

Allied land based aircraft were picking up the tempo of their attacks. Four dozen B-24s struck barracks and airfields at Davao. They followed up with a similar attack three days later. The range of search missions (up to 1,000 miles for PB4Ys) was being increased as well as the reach of attack missions.

Within an hour of the alert from Leyte Gulf V-Adm. Teraoka ordered Cebu base to launch attacks against the landings with such strength as was available. It seems likely weather conditions kept this from happening. Presumably, 2nd FD sent similar orders to its assault and search aircraft in position to execute them. The midmorning sighting of a single-engine aircraft by the minesweeping group was probably an army short range reconnaissance plane.

Shortly after midday a navy reconnaissance plane was sighted by the minesweeper group. Its 1230 sighting message reported a battleship, two cruisers, and eight destroyers. A thirteen plane attack group launched a couple hours later turned back due to weather but still lost five land attack bombers apparently to operational causes. Among those lost was Lt. Cdr. Yoshinobu Kushimoto flight leader of K704.

The events of the day resulted in a Japanese Navy declaration of Operation Sho-1 as fully operative effective the following day. The Philippines would be the site of the decisive battle not just for air operations but for the fate of the Empire. Japanese defensive operations had inflicted little damage and offensive air operations during the day had been completely ineffective.

Main units of the Japanese fleet concentrated near Singapore and in the Home Islands were mobilized. An Allied force built around British fleet aircraft carriers HMS Indomitable and HMS Victorious struck Car Nicobar on the western tip of Sumatra as a diversionary effort to support the Leyte landings. A follow up strike came two days later.

Having learned that his key naval forces would not be able to sortie for the Philippines for a few days C-in-C Combined Fleet Toyoda returned to Shinchiku from Takao on his way to his headquarters in Japan. The delay in X-Day, when a decisive naval battle was expected to take place, meant Japanese warships would be too late to break up the actual landings. The transports involved in the initial landings would be able to unload and leave the area before they could be destroyed. It did leave the possibility that the ground forces that were landed could be cut off from supplies and left to die on the vine or withdraw. Two years earlier American naval victories in the Guadalcanal campaign had done that to the Japanese.

During the day Admiral Onishi proceeded to Manila from Takao by air.

Philippines map

October 18. This proved to be a pivotal day. Combat operations heated up and critical decisions were made. In the invasion zone progress on minesweeping and under water reconnaissance/demolition took place. Bombardment of Japanese positions on Leyte began. Homonhon Island (where Magellan first landed in Asia during his ship’s world circling voyage) in the middle of the entrance to Leyte Gulf was occupied.

Undoubtedly orders for routine morning searches to be conducted had gone out from Manila the previous evening. Search planes did sortie from Luzon to scour the sea to the east. While weather over Luzon was generally good, to the east three of Halsey’s carrier groups had partial cover provided by less favorable conditions. Conditions which did not, however, preclude them from launching fighter sweeps and attack missions. To the south the first escort carriers of Task Group 77.4 arrived east of Leyte. The previous day’s bad weather had abated and morning flying conditions over the small carriers were good. Residual stormy weather to the west gradually cleared making targets available on Leyte but hindered early morning operations from Japanese airfields on Cebu and Negros. Previous damage inflicted by SWPA land based aircraft was the apparent reason no Japanese searches were flown from Mindanao.

Admiral Onishi who was imminently to assume command of the 1st Air Fleet broached the question of the adoption of crash tactics with Admiral Teraoka. The air fleet staff was brought into the discussion. The conversations may have been delayed by ongoing operations. By 0800 Teraoka and Onishi were aware that American carrier planes were attacking targets in the Manila area. They soon learned that planes from another carrier force were attacking Aparri and Laoag in northern Luzon and that airfields of the Clark complex had been hit. Farther south air attacks on the Tacloban area of Leyte and Cebu were reported. If it had not been obvious previously, these events made evident that claims of the destruction of American carriers announced by Imperial General Headquarters were wishful thinking at best.

Halsey’s carrier air groups flew over 550 offensive sorties. Task Group 38.2 flying against targets in northern Luzon met no aerial opposition but claimed twenty-one aircraft on the ground and shot down one floatplane as it was taking off. Considerable damage was inflicted on shipping. Task Group 38.1 mounted successive fighters sweeps of thirty and twenty Hellcats against Clark as well as two strike missions. An estimated thirty-five Japanese fighters opposed each sweep. Thirty were claimed destroyed with two Hellcats lost. The strike missions encountered no aerial opposition. A Task Group 38.4 fighter sweep by two dozen Hellcats against Nichols and Nielsen airfields near Manila was diverted to Clark due to poor weather over Manila. Of an estimated thirty intercepting Japanese fighters eighteen were claimed destroyed. Subsequent strike missions in the Manila area hit the airfields and harbor, reporting aircraft destroyed on the ground, as well as damage to shipping.

The American carriers were not attacked. Radar picked up few bogeys during the day. There was a couple brushes with search planes. One land attack bomber of K704 was lost on a search mission out of Clark. One Ginga suffered medium damage. The navy’s base air force apparently sent a strike force of several planes after the carriers, but none made contact.

Task Group 77.4 mounted 144 offensive sorties for the day. Among other damage they claimed two air kills and fourteen aircraft on the ground. The Japanese navy sent six fighters and dive bombers against ships in Leyte Gulf. They reported hits on a destroyer. Details of possible army missions are not available. Only minelayer U.S.S. Preble (converted from a WW1 destroyer) recorded an attack. Two aircraft identified as Vals dropped four bombs which caused no damage. For the reasons mentioned previously the identification of the aircraft as Vals is dubious.

For the day the total of aircraft destroyed or damaged in the air or on the ground claimed by U.S. carrier based aircraft was well over one hundred. Air combat victories are often overstated and some of the ground claims may have been derelicts or dummies. However, there is little doubt both Fifth Base Air Force and 4th Air Army suffered serious losses during the day. The army lost sixteen operational aircraft including several Type 4 fighters in addition to unserviceable planes. The Navy also suffered several losses.

A stark reality faced Japanese leaders at their respective headquarters in Manila. Operation Sho-1 had been initiated and its X-day set for 25 October, with Y-day involving maximum air support set for 24 October. Air support for the forthcoming naval action was critical. While this affected both navy and army air efforts, the navy had primary responsibility. The Americans had massive aviation support. What did the Japanese have? Especially, what did they have that could be brought to bear in less than a week? The Americans’ air power advantage needed to be seriously diminished if not neutralized by the twenty-fourth.

As darkness fell over Manila General Tominaga and Admiral Teraoka in their respective headquarters surveyed their resources. For the army operational strength was 25 fighters, 10 attack bombers, 4 reconnaissance planes, and 30 heavy bombers; sixty-nine operational aircraft out of 115 on hand. While army bombers could certainly be directed to attack missions significant numbers of them were engaged in transport operations of various kinds. For the navy operational numbers were: 15 carrier fighters, 2 carrier reconnaissance/dive bombers, 3 land attack bombers, 2 Ginga land bombers, and eleven Tenzan (Jill) carrier attack bombers, eight of the latter had just arrived during the day. Total operational strength was only thirty-three. Barely two weeks earlier the 1st Air Fleet had 134 operational out of over 180 available combat aircraft. As the first full day Sho-1 beckoned there were barely a hundred Japanese combat aircraft ready for operations under the key navy and army commands and not all of these were in place to execute operations. Work to put additional aircraft into serviceable condition was in progress.

During the day discussion of Onishi’s proposal to adopt crash tactics was being considered with utmost seriousness. Admiral Teraoka recorded some of the opinions expressed during staff discussions about crash tactics during the day.[1] The main points were that (1) it would be dangerous for the surface fleet to engage in the decisive battle unless the enemy’s carrier based air power could be destroyed or seriously damaged; (2) time to accomplish this was short; (3) conventional tactics are ineffective; and (4) available airplanes are few in number. The discussions went on to address the best way to obtain volunteers for such attacks with fighter pilots who had been training in bombing attacks seen as the most likely candidates. How best to approach them was discussed. Moreover, it was suggested if suicide attacks were initiated by fighter pilots other units would follow their example. If the navy became committed to such attacks the army would probably follow suit. Thus, while there was an immediate situation to address, it was mooted that once suicide attacks were initiated they might not be confined to one unit or one battle.[2]

After staff discussions and the exchange of opinions it was decided suicide tactics were “the only possible salvation for the nation.” Additionally, it was decided to allow Onishi, soon to assume air fleet command, to organize the units at his discretion. There is no indication that Teraoka or Onishi thought they were exceeding their authority by reaching such a decision. It will be recalled that up until two days previously Onishi had been in Admiral Toyoda’s presence for several days. There is no available evidence whether a discussion of crash tactics with C-in-C Combined Fleet took place, but Onishi was apparently confident that the decision would not be second guessed.

[1] Pertinent quotations from Teraoka’s diary appear in Bates Vol. II (note 1, Part I), The Divine Wind (note 2, Part II) and The Kamikaze Attack Corps chapter in David Evans, ed., The Japanese Navy in World War II 2nd edition, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press (1986).

[2] A co-author of The Divine Wind, Cdr. Nakajima, who was not present asserts that he believed Onishi intended the suicide attacks to be limited to the few units organized in 201 Kokutai. However, the number of units, pilots and planes involved was expanded even before the first successful crash-dive attack.