Ten Days to Kamikaze is a series that explores the decision-making process and implementation of Japan’s use of suicidal crash dives during World War II. It provides an in-depth review of the critical ten-day period and examines the background leading up to those decisions. The series will be presented in several parts, starting with Part 1, and subsequent parts will be released on a weekly basis. It concludes with a summary of the justifications for these extreme actions and considers the potential outcomes if the war had not ended when it did.

If you are just joining the series, you can read previous posts here:

Now on to Part II – The Kamikaze Idea!

“What’s past is prologue,” saith the Bard. The critical ten days reviewed in this study did not exist in a vacuum. Rather, a variety of thoughts and events coalesced to set the stage which the actions and decisions that occurred in October 1944 brought to a head. Background and context do not mean that events as they happened were inevitable or predict what the subsequent reaction to those events would be.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica (1943 ed.), Japan’s national suicide rate (21.0 per 100,000 population) in the mid-1930s was just about in the middle of the highest and lowest rates of the twenty-eight countries for which data was presented, about the same as for France. Late in the war, the U.S. military surveyed “Self-immolation as a Factor in Japanese Military Psychology” [1]. The conclusions reached in the study may not have been entirely accurate, but numerous examples of self-sacrifice being extolled in interrogation reports and captured military documents of both a private and official nature were recorded. Juxtaposed with general population suicide data, the study suggests a different attitude or ethos in the military. The basic concept of valuing loyalty and honor above life is, however, an ancient one exemplified by the Bushido code of the warrior Samurai. The study could not necessarily assess the strength of contrary but unarticulated views.

An early example of varying views arose in the Japanese Navy. All the midget submarines and their crews launched against Pearl Harbor at the outset of the war were lost. The crewmen were considered heroes (other than one who was captured). In early 1942, Commander Rikihei Inoguchi was in the navy personnel office. When asked to supply some exceptional officers for a special mission, he asked what the mission was. He was told Admiral Yamamoto, C-in-C Combined Fleet, had the idea of sending midget submarines against Sydney and Diego Suarez harbors. Inoguchi opined that sending the midgets against Pearl Harbor might have been justified in such a profound and risky operation. However, sending midget submarines into shallow, constricted harbors was virtual suicide. According to Inoguchi’s recollection, he said, “No matter how great and worthy Admiral Yamamoto is, if he resorts to suicide tactics, historians will condemn him a hundred years hence. [2]” Inoguchi’s attitude was to change. Midget submarine operations were later mentioned in the official explanation or defense of the commencement of suicide tactics.

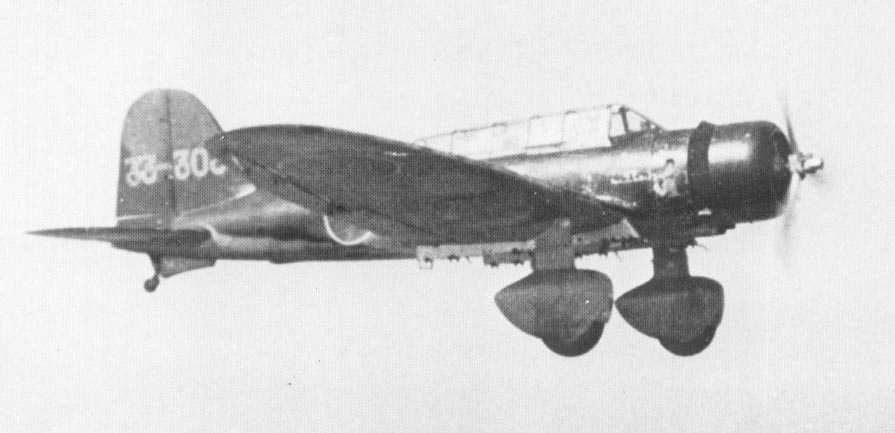

The term jibaku was often used in official reports describing aircraft losses (in the Japanese English language press, it was typically translated as “self-exploded” or “crashed into an enemy objective”). Jibaku implies intentional self-destruction aimed at causing damage to others; it was generally understood this occurred only when the pilot or aircraft had been disabled. In May 1943, when Sgt. Tadao Oda of the 11th Flying Regiment (Hikosentai) collided with a B-17 over New Guinea resulting in the destruction of both the Flying Fortress and his Type 1 fighter, the action was lionized in the Japanese press as the first example of a ramming attack. Oda was posthumously promoted two ranks. Lt. Jiro Yokozaki reputedly crashed into a bomber attacking northern Japan in September 1943 [3]. The act was portrayed as intentional and characterized as heroic in news headlines. These reports, both in press and radio, were monitored in the U.S. where apparently they were considered mere rhetoric and not anything about which to be concerned. Clearly, an intentional act took place on June 23, 1943, when a navy Type 97 model 2 (B5M1) attack bomber of Air Group 932 flown by Lt.(j.g.) Yuji Kino confronted a formation of B-24s over the Netherlands East Indies. The fixed landing gear torpedo bomber had no forward firing armament and no mission to intercept bombers while on patrol. The collision resulted in the crash of both the attack bomber (identified by the Americans as a Nate fighter) and the B-24 with both crews lost. Though not as widely hailed as some of the other events noted above, Kino’s action was officially recognized by Admiral Koga, Commander of the Combined Fleet [4].

A Type 97 model III carrier attack plane (B5M1) of the 33rd Air Group (later Air Group 932) the type flown by Lt. (j.g.) Kino in June 1943.

On May 27, 1944, Maj. Katsushige Takada responded to news of an American landing operation at Biak Island by leading four Type 2 two-seat fighters of his 5th Hikosentai in an attack. This was carried out without bombs using only the fixed cannon of the fighters. All four fighters were shot down. Takuda’s aircraft was damaged by anti-aircraft fire, and he attempted to crash into the destroyer U.S.S. Sampson. He narrowly missed the destroyer and crashed close to the SC-699. Part of his aircraft penetrated the hull and, along with resulting fires, seriously damaged the ship and inflicted crew casualties. Takuda and his fellow airmen were cited in a proclamation from Gen. Terauchi, the Japanese Army air commander in the region. His exploit, which was characterized as a “suicide attack” in one official communication, was made known to the Emperor [5].

Published almost exactly a year before the initiation of Kamikaze attacks, a Nippon Times article not only extolled the virtue of self-sacrifice by Japanese pilots but contrasted it with the feckless behavior of American pilots:

“It is an honor to die in the cause of the country,” is the basic spirit of all Japanese soldiers…The fact that American airmen attempt to save themselves when their planes are shot down, by means of parachutes, is eloquent testimony of the “self-first” attitude of American fighters. A Japanese pilot would never submit to the dishonor of being taken prisoner but prefers to resort to self-blasting. [6]”

The term Kamikaze is used so indiscriminately today and even in literature dating from the World War II era that it is worth noting that the term was not used in considering the possible adoption of suicidal ramming or crash tactics. The term, susceptible to two different pronunciations of the Japanese ideograph, was not even applied to officially ordered suicide attacks until several days after the first attacks and even then was not noticed by the participants most affected, suicide pilots. It originally referred to an organization, not a tactic. The term was publicized in an Imperial General Headquarters communique, inaccurately rendered as Kamikaze in English transliteration, thereafter entering common and generic usage.

The Japanese army studied crash tactics against aircraft beginning in 1943. One publication pointed to the destruction American and British heavy bombers were raining on German cities. Mention was made of the development of the B-29, implying Japanese cities might be similarly attacked. A captured document, “Reference on Ramming Tactics Against Bombers” (August 1943) [7], contained a “Mid-air Ramming Chart” which recorded the results of aircraft collisions (mainly Type 97 fighters) illustrating the vector and impact point of the collision and whether the pilot had survived. A translated pamphlet issued in February 1944 was titled “Views of the Use of Crash Tactics in Aerial Protection of Vital Defense Regions – No. 2” [8]. Although the possibility of the attacking pilot surviving was contemplated, the document stated, “A lofty spirit of self-sacrifice for the good of the country should be inculcated within the force, which should be designated by such a title as will emphasize the honorable and glorious nature of such a function.” Coincidence or otherwise, honorific names were subsequently adopted for Navy suicide units.

Along with discussions on improving existing weapons and tactics, informal discussions on the subject of organizing special attack units took place in the Army section of Imperial General Headquarters as early as May 1944 [9]. These discussions took substance in August 1944 with regard to crash tactics against ships with an order to modify a handful of the Army’s latest twin-engine bombers (Type 4 heavy bomber, Hiryu) with special equipment, a reduced crew, and two 800kg bombs. The small number of bombers modified suggests this was intended for a future undefined special or extreme threat. As noted above, the likelihood of B-29s being used to attack Japanese cities and the possible use of ramming tactics was the subject of a pamphlet issued months before the first B-29 attack on a target in Japan. Interestingly, despite the early contemplation of ramming tactics against heavy bombers, such tactics, while not unknown, were carried out on only a modest scale.

In August 1944 the Japanese Army Air Force authorized the conversion of a few Type 4 heavy bombers (Ki 67) to a special suicide attack configuration.

The Japanese were not the only pilots to engage in aerial ramming tactics. There are several examples of Soviet pilots that resorted to ramming on their own initiative to bring down German aircraft (Taran tactic) in the early days of the war over Russia with a mixed record of survival [10]. In April 1945, poorly trained German pilots were sent in mass on a mission to ram American bombers (Sonderkommando Elbe) [11]. Remarkably, in response to the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Air National Guard pilots flying F-16s lacking missiles and armed with only training ammunition for their guns resolved prior to take-off to engage in ramming tactics to prevent an attack on vital targets in the District of Columbia [12].

Thinking about crash tactics aimed at ships as well as heavy bombers had been going on in the Japanese navy at about the same time that the army was considering such tactics. By 1944, the navy had its own fighter crashes into bomber stories, including two instances in which the pilot survived. The contemplation of special weapons that employed suicide tactics was mooted as early as March 1944. After the defeat of Japan’s carrier fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, proposals to adopt ramming tactics headed toward Combined Fleet headquarters from multiple vectors. One was the proposal of Ensign So-ichi Ota of the Yokosuka Air Technical Arsenal to develop a piloted rocket-propelled flying bomb that could be launched from a land attack bomber (Ohka or Baka bomb). Work on the project began that summer. V-Adm. Onishi, head of aeronautic developments at the munitions ministry, would have been aware of this. Other technical projects involving suicide or near-suicidal tactics were the Kaiten piloted torpedo and Shinyou high-speed motorboat.

The Japanese Navy developed a prototype rocket propelled suicide attacker. Production of the Ohka was authorized in late 1944.

One of the carriers that survived the Battle of the Philippine Sea was Chiyoda. Her captain, Eichiro Jo, wrote a report recommending adoption of crash tactics (Jo volunteered to lead the effort) on a limited basis. Jo’s Carrier Division commander, R-Adm. Obayashi, apparently concurred, and the recommendation reached V-Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa, who forwarded it to Combined Fleet headquarters in July. The recommendation was referred to air operations officer Capt. Mitsuo Fuchida, and no action was taken. V-Adm. Onishi was aware of Jo’s recommendation and did not concur at the time. Jo’s views on the subject had developed much earlier observing combat operations in the vicinity of Rabaul. In August, Fuchida received a letter from an old colleague commanding Air Group 341 at Katori airbase. Capt. Motaharu Okamura had shared his initial ideas on ram attacks with V-Adm. Fukudome as early as June. His letter to Fuchida contained a recommendation much like Jo’s but implied a grander scale. Admiral Toyoda was made aware of both recommendations but took no express action to approve or disapprove the concept [14]. After a test flight in October, the rocket bomb project proceeded to initial production, and Okamura was assigned to guide the project to potential operational use. V-Adm. Kimpei Teraoka, Okamura’s commanding officer, in August 1944 about to leave for the Philippines to assume command of the 1st Air Fleet, most likely heard of these developments. In October 1944, Capt. Inoguchi was an operations and plans officer with the 1st Air Fleet. Inoguchi, who became an advocate of suicide tactics, stated in his postwar interrogation by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey that he was not aware of discussions of crash tactics at Imperial General Headquarters, and the idea arose independently in the Philippines. This suggests that whatever awareness Onishi might have had of the various discussions recounted above, he did not invoke them in support of initiating a policy of crash tactics.

U.S. carrier raids on the Philippines in September showed the relative ineffectiveness of conventional tactics, especially considering Japan’s numerical inferiority. In those raids as well as other operations in the Pacific, U.S. carrier task forces were able to hit targets with virtual impunity for their ships and modest losses among attacking aircraft. Senior leaders knew hopes for Japanese victory were dimming. If there was to be an outcome other than a humiliating surrender, a new approach was needed. Crash tactics might well be what was needed. As U.S. invasion forces were on their way to the Philippines in the second week of October 1944, crash tactics had been a matter of discussion for months, but there was no policy regarding such tactics emanating from either Tokyo or Manila. The average combat pilot was not privy to discussions at high levels of command but would have been aware of the glorification of crash tactics in the press.

[1] Allied Translator and Interpreter Service (ATIS) Research Report No. 76. About the same time as Britannica’s suicide data was collected Will Durant’s The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage was published (Simon & Shuster, 1935) containing a discussion of Bushido and seppuku including the example of honor suicide among sailors of the Japanese navy (avoiding capture) in the war with Russia in the early 20th Century (p. 848).

[2] Inoguchi et al, The Divine Wind, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press (1958), p. 63.

[3] Nippon Times (Oct. 31, 1943) featured the action with three cartoon-like illustrations under the heading Stranger Than Fiction, the final caption read: “Failing to bring the enemy leader down after repeatedly firing into him Lieut. Yokozaki deliberately dashes his plane into him and crashes into the sea after the enemy bomber.”

[4] Citation, To the Carrier Attack Plane of the 932nd Air Group, commanded by Reserve Lt (jg) KINO, Naval Gazette # 4583 (6 January 1944), C-C TRANS & INT # 26.

[5] Exploits of Takada Fighter Unit Brought to Attention of Throne, Nippon Times, July 26, 1944.

[6] American Pilots Unskilled, Fighting Morale Inferior, Nippon Times, Oct. 22, 1943.

[7] Allied Translator and Interpreter Service (ATIS) Bulletin No. 1432, item 1.

[8] Advanced ATIS (ADVATIS) Translation No. 86

[9] U.S. Army, Reports of General MacArthur, vol. II – Part II (1966), p.563.

[10] Hardesty & Grinberg, Red Phoenix Rising, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press (2012), pp.31-32.

[11] Bowman, Clash of Eagles, Barnsley, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Books (2006), p. 232.

[12] The pilots were Lt. Col. Marc Sasseville and 1Lt. Heather Penney, 113th Fighter Wing, D.C. National Guard. Lt. Gen. Sasseville is currently (2023) Vice Chief of the National Guard Bureau.

[13] More than 600 Ohkas were produced but less than 100 were used operationally and they were credited with a single destroyer sunk and several ships seriously damaged. Like army heavy bombers they were a small fraction of the Kamikaze effort.

[14] According to Prange, God’s Samurai, Washington: Brassey’s Inc., (1990) p. 129, Fuchida took Toyoda’s lack of express disapproval as a “less than enthusiastic…approval”. Fuchida shared the ideas presented by Okamura and Jo with senior colleagues who expressed agreement with them. Despite Fuchida’s impression, no express policy or order regarding crash tactics resulted from discussions at Combined Fleet headquarters.