This article constitutes a preliminary effort to relate the victory claims of Chief Petty Officer Takao Okumura on 14 September 1943 to Allied activities and actual losses. Okumura’s ten victories in a single day are believed to constitute the highest one day claim of any Japanese navy fighter pilot during the war. For this feat Okumura was awarded a citation and was to have been presented with an inscribed ceremonial sword by Vice-Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, commander of the Southeast Area Fleet (naval theater commander). Okumura was killed in combat before actually being presented with the sword.

Okumura’s Career

Takao Okumura was born February 27, 1920 in Fukui Prefecture located in the west central part of Japan’s main island of Honshu. Fukui Prefecture had a small population. Before its industrial development agriculture and fishing were its economic mainstays. Educational and career opportunities for its youth were limited. At the age of fifteen Okumura joined the navy. Within a few years he gained a coveted spot in the naval aviation training course for enlisted men. He graduated in 1938. After operational training he was sent to China in 1940 as a fighter pilot flying the Type 96 carrier fighter (A5M).

In October 1940 Okumura was part of a detachment of the 14th Air Group flying the new Type Zero carrier fighter (A6M2) from Hanoi, French Indo-China. On October 7, 1940 Okumura flew one of seven Zeros escorting bombers raiding the Chinese base at Kunming. Kunming was a training base but also home to a number of Chinese fighters. His group claimed fourteen air victories and four aircraft destroyed on the ground. Two pilots each claimed four victories. Okumura had an outstanding debut in combat being one of the pilots claiming four victories. He also had a witness on the ground that was to become famous. Claire L. Chennault, subsequently commander of the American Volunteer Group or Flying Tigers, caught his first glimpse of a Zero (he considered it superior to earlier Japanese fighters) during this action.

The Zero fighter claimed many victims over China. Most of the Chinese fighters that survived avoided combat and Okumura did not repeat his success later in China or early in the Pacific war. Excitement returned soon after he joined the fighter unit of the small aircraft carrier Ryujo in July 1942. On August 24, 1942 Ryujo was sunk in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Okumura’s fighter was damaged in combat and he force landed on Guadalcanal. After his rescue he joined the Tainan Air Group and flew many missions over Guadalcanal September-November 1942 during which he was credited with fourteen victories. In one of his early combats with the Tainan Air Group on September 13, 1942 almost exactly a year before his ten-victory day Okumura claimed a triple victory against F4F Wildcats but most likely got no more than two. On October 2nd he claimed a double victory against SBD dive bombers. Though damaged neither Dauntless was actually the immediate victim of his guns but both were later finished off by other Japanese pilots. It should be noted that while Okumura was officially credited with his victories in China most Japanese fighter units did not have official victory lists for individual pilots. Generally experienced Japanese pilots were not required to report that they had seen their victim actually crash. Their judgment that they had inflicted sufficient damage to down their target was usually accepted as sufficient to report a victory for the unit. Sometimes claims were recorded as uncertain or merely damaged. Victories can sometimes be deduced for individuals from unit records but an official ace list or comprehensive individual victory list does not exist for Japanese pilots.

Okumura returned to Japan with Tainan (renamed 251) Air Group late in 1942. The unit had been decimated and was slowly rebuilt. In May 1943 when Air Group 251 deployed to Rabaul Okumura was transferred to Air Group 201 which was also rebuilding and in need of experienced pilots as much as Air Group 251. In July 1943 after the invasion of New Georgia in the Solomon Islands, Air Group 201, equipped with Zero model 21s and 22s, was also transferred to the area with most experienced pilots island-hopping south and the remainder of the air group transported to Truk via aircraft carrier and then flying to Rabaul. Okumura was soon in combat, usually flying from Bougainville Island, and scored additional victories.

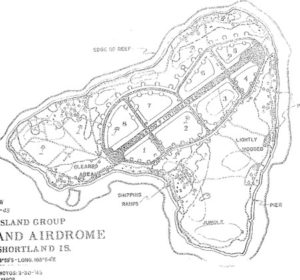

In September 1943 Okumura was still with Naval Air Group 201. At that time it was part (along with fighter Air Group 204 and light bomber Air Group 582) of the 26th Air Flotilla. Following a recent reorganization the headquarters, 26th Air Flotilla, had come under the command of Rear Admiral Munetaka Sakamaki just relieved as commander, 2nd Carrier Division whose fighter units were integrated with the land-based units at Buin. In mid-September Allied photo reconnaissance usually sighted about sixty Japanese fighters in standby positions on Buin airfield although at times the fighters were dispersed between Buin, Buka, and Ballale, or temporarily shifted to Rabaul.

The Raids and Okumura’s Claims

There were six Allied raids directed against Buin and Ballale on 14 September 1943. The first raid was before dawn and the twelve B-25s involved struck other targets or aborted due to weather. The other five are described below. Events as recorded by Teijiro Shiratori a navy press corps reporter are shown in italics and are primarily direct quotes with minor paraphrasing and some added notations shown in brackets. Shiratori’s reporting is followed by a summary of events from Allied reports.

No. 1 – It was 6:30 a.m. [8:30 Allied time] when we received a report enemy planes were winging toward our base. Our fighters [20 from Air Group 201 and 23 from 204] took off immediately and after reconnoitering for about 35 minutes [7:05/9:05] at last located the enemy squadron. The weather was clear with fluffy white clouds dotting the sky. The enemy formation was composed of 11 Consolidated B-24’s and about 30 fighters. A fierce battle ensued. Petty Officer Okumura shot down one Vought-Sikorsky while seven fighters were accounted for by his comrades. Then our planes closed in on a large-type foe plane Petty Officer Okumura scored the first hit which was followed by the others until finally the enemy plane plunged to its doom in a ball of fire and smoke.

At 0900 ten B-24s covered by F4U’s dropped 120-pound fragmentation clusters from 22,000 feet. Clouds obscured results. Thirty Zekes and two Tonys (“Zeke”, American codename for a Zero; “Tony”, American codename for an Army Type 3 fighter, none were present) reportedly attacked the B-24s but most of the repeated attacks were not closely pressed with the exception of attacks on one B-24 that was hit and left the formation. B-24s claimed two Japanese fighters. Seventeen F4Us encountered 20 to 24 Zekes and then another eight at 25 to 28,000 feet. Claims were for 4 Zekes and a Tony. No F4U’s were lost but five were shot up and “out of commission indefinitely.” One B-24 (#730) received numerous 20mm and 7.7mm hits and was badly shot up with a crewman wounded during a ten minute battle. A twenty millimeter hit knocked out the oil cooler in No. 1 engine; the bomber descended from 23,000 to 9,000 feet before recovering and returning to base.

No. 2 – As soon as the lookout espied enemy craft, several of our planes took off…The enemy was quick to make his getaway and the 12 Consolidateds and 30 fighters disappeared…

At 1031 twelve B-24s escorted by 23 F4Us dropped fragmentation clusters from 21,000 feet. Hits were observed along the SW side of the runway. Fourteen fighters had just taken off and six were in the process as the American force approached the field. Japanese were much too late to intercept.

No. 3 – It was some 40 minutes later [after Raid 2] when our men…were about to land when they were ordered to stay in the air. Just then maintaining an altitude of 6,000 meters 40 Bells and Grummans became visible flying toward the Japanese planes. In the ensuing combat that lasted for 30 minutes 22 enemy planes were destroyed of which Okumura accounted for two Bells and a Grumman…Due to lack of fuel some Japanese planes landed at XX base [Ballale] while Okumura and one other returned to Buin.

At 1202 ten B-24s dropped fragmentation clusters from 21,500 feet (P-40 report says there were nine B-24s). They were escorted by eight U.S. P-40s (seven model F’s and one M) and sixteen RNZAF Kittyhawks. Three of 12 Zekes attacked B-24s. Six to eight Zekes made individual attacks on the high cover P-40 flight at 24,000 feet. Kittyhawks observed the combat but were not engaged. Four P-40s returned with an aborting flight leader. Two P-40s failed to return. One shot up P-40 crash landed at Segi and slid into the water (loss listed as “combat operational”; not publically admitted as a combat loss). The pilot was not recovered. The other P-40 returned badly shot up. No Bell P-39’s were involved.

No. 4 – Shiratori does not mention Raid No. 4.

At 1305 nine PB4Ys dropped fragmentation clusters from 23,000 feet on Ballale. They were escorted by ten F4Us three of which strafed the strip and shot up two Zekes and a Betty. There was no interception.

No. 5 – Directly upon landing [after Raid 3] the planes were attended by the ground crew… [Okumura’s plane was refueled and armed but he took off before his oxygen was replenished]. The sky seemed black with enemy planes which numbered 50 bombers and 60 fighters…Nothing daunted our hardy fliers went straight into the enemy formation shooting down one after another until 20 were destroyed during the 30 minute battle. Petty Officer Okumura shot down one bomber and four Grummans thus adding another 10 to his already amazing record of 44 enemy craft…[but Air Group 201 lost two Zeros and Air Group 204 lost four while a total of nine aircraft were destroyed on the ground during the day].

At 1313 24 TBFs and 34 SBDs dropped 2000-pound and 1000-pound bombs on the Ballale runway scoring several hits. Escort was provided by 40 F6Fs and 15 P-39s. The F6Fs of VF-33 followed bombers in their dives and were engaged at low altitudes. VF-38 and VF-40 had brief engagements and only claimed probables. The P-39s had no contact. VF-33 claimed eight Zekes. Two of their F6Fs were listed as “combat operational losses”. One F6F ditched off shore at Munda and the other crash landed on the strip at Munda both were badly shot up and their pilots were wounded. One F6F from VF-38 received a few 7.7mm hits. Their pilots reported seeing several Zeros attack the TBFs. Other reports say only two Japanese fighters made passes at the bombers reportedly without causing damage. Four TBFs were damaged; victims of AA according to US reports.

Brief analysis of the claims

Okumura’s Raid No. 1 claims of a Vought-Sikorsky or F4U Corsair and a shared B-24 while not fully substantiated might well be considered valid. Okumura claimed one of a total of eight F4U’s claimed by the Japanese. Five were badly shot up and out of commission “indefinitely” probably as write-offs. Japanese attacks on the Corsairs apparently scattered their formation because the B-24’s reported no Corsairs were in the area when they came under attack. One B-24 was shot out of formation and descended precipitously and was last seen by the Japanese trailing fire and smoke. The ultimate fate of this aircraft (probably B-24D No. 41-23730) after it returned to base has not been determined but it seems quite possible that it too was a write-off. As mentioned earlier in most Japanese navy air unit’s it was not necessary for an experienced pilot to see an aircraft crash to claim it as a victory. The judgment of an experienced pilot that sufficient damage had been inflicted to destroy the victim was sufficient. Okumura may well have “destroyed” a Corsair and a B-24 even if he did not shoot them down in the combat area.

Okumura’s Raid No. 3 claims are less susceptible to substantiation than his Raid No. 1 claims. Since the Japanese claimed twenty-two victories (apparently twenty were for fighters) and only three American fighters were lost, the chances that one pilot actually got all three hardly seems likely. The best that can be said for certain is that Okumura may have contributed to the demise of three fighters that were among twenty also claimed by several other Japanese pilots. The misidentification of P-40’s as ‘Bells’ (P-39’s) is unremarkable but Okumura’s claim for a Grumman in this combat is less understandable. Perhaps he should be given partial credit for three victories.

Okumura’s Raid No. 5 claims constitute a mixed bag. Only two F6F’s were lost and so his claim for four cannot be credited. He may have been responsible for the loss of those two or contributed to their loss. The bomber claim is harder to parse. The Japanese claimed eleven bombers. Though not entirely clear apparently five were credited to fighters and the others to ground batteries. An Americans intelligence summary asserts that four damaged TBF’s were hit by ground fire. Thus, while Okumura was probably one of the Japanese fighters attacking the bombers he did not shoot down a bomber in this raid and based on the American reports he may not have even inflicted any damage. Okumura may have downed two Hellcats.

Instead of ten victories Okumura may have been involved in shooting down or damaging beyond repair seven American planes. The Japanese acknowledged the B-24 as a shared victory but it seems highly likely that most of Okumura’s other victories were actually the result of joint action with other pilots or at least the victim was claimed by multiple Japanese pilots. Depending on one’s point of view he might be credited with anywhere from two to seven victories instead of ten.

In other famous multiple kill events of World War II Edward “Butch” O’Hare received the Medal of Honor for downing five Japanese bombers in a single mission in February 1942. Actually he shot down three and damaged two others. Neel Kearby received the Medal of Honor for shooting down seven Japanese aircraft in a single mission in October 1943. Only two of his claims can be verified. The German ace Hans-Joachim Marseille was credited with shooting down seventeen British aircraft during multiple missions on September 1, 1942 over North Africa. Under careful scrutiny all seventeen cannot be verified but it does appear he accomplished the remarkable feat of shooting down about a dozen enemy planes in a single day. Whether Okumura’s ten-victory day should be equated with these and other similar events is for the reader to decide. While the extent of Okumura’s success is clouded by the confusion of multiple large scale raids and general over claiming of victories by the Japanese pilots involved there is no doubt he engaged in all the actions in which he claimed victories and that there were American losses in all those actions. This is in strong contrast to the most famous Japanese multiple claim event Sgt. Anabuki’s claim of three B-24’s and two P-38’s shot down in one mission in October 1943. The author’s research has shown that Anabuki’s claims were a complete hoax [Error Oft Repeated – The Anabuki Hoax].

Okumura’s Demise

In late 1943 the Solomon Islands were the primary zone of Japanese naval air action in the Southeast Area while the Japanese army took responsibility for New Guinea. This was not a strict division, however, and the navy sometimes operated over New Guinea especially against naval targets. Such was the case on September 22, 1943 when the Americans and Australians carried out an amphibious landing near Finschhaven, New Guinea. Daylight torpedo attacks using Type 1 land attack bombers had proved to be extremely hazardous and costly for the Japanese for more than a year and were rarely used. When enemy fighters were present fighter escort had to be provided at low level. The daylight attack on September 22 was the last such attack in the area. Not only were such attacks hazardous for the bombers which had to face close range heavy anti-aircraft fire from ships but both the bombers and their fighter escort frequently ran into heavy enemy fighter interception which under the circumstances inevitably enjoyed an altitude advantage. A recent similar attack (June 30, 1943) had resulted in disastrous losses both to attacking bombers and their escorting fighters.

In attempting to describe Okumura’s final mission it should be recognized at the outset that the actual details of his demise cannot be ascertained. The Japanese merely recorded that he failed to return from the mission. The Americans, of course, did not even know he was involved. However, an outline of the action and some data that may point to Okumura can be related.

Only a moderately sized affair by standards of the day the landing of an Australian Brigade at Finschhaven loomed large in Japanese eyes. Earlier in September Salamaua and Lae had fallen to the Allies. These were the main defense points that kept Japan’s “Bismarck’s Barrier” the line from the northern Solomons, across New Britain, to the Huon Gulf, from being breached. The fall of Lae and Salamaua had been bad enough but at Finschhaven the Allies arrived at the “barrier” itself on Vitiaz Straight from which place they could invade western New Britain or push westward along New Guinea’s north coast or both.

Bad weather limited the response of the Japanese army air force to a few early morning attack and reconnaissance sorties. To confront the invasion force of warships, transports and landing craft the Japanese navy at Rabaul mounted an attack force of just eight land attack bombers armed with torpedoes and thirty-five escorting fighters. Most of the fighters were from Rabaul-based Air Group 253 but some were from units usually based at Buin. The bomber force was most probably limited in number by the availability of fighters to provide escort. The bombers of Air Group 751 based at Kavieng on New Ireland made rendezvous with the fighters over Rabaul and proceeded to the target. Near the target a dozen fighters stayed close to the bombers as they descended to low level for torpedo attack some stayed right with the bombers as they penetrated a broken layer of low clouds. The other fighters covered them from an altitude of about 5,000 feet or higher. Lt. Shiro Kawai led twelve Zeros from Air Group 201 with Chief Petty Officer Okumura leading one of his sections.

Approaching the target in spotty weather the bombers were confronted with massed anti-aircraft from ships that had been alerted by radar early warning. The bombers pressed their attacks with great daring through this maelstrom but failed to score a single hit. The Americans could account for seven torpedoes which in one case passed under a ship without exploding and others that came close or exploded in the wakes of ships. Several dozen American fighters P-38s, P-40s and P-47s assailed the Japanese force. The ships claimed seven bombers while American fighters claimed eleven. In the end six bombers were shot down, one force landed at Cape Gloucester, and one damaged bomber landed at Rabaul. American fighters claimed twenty-one Zeros (Zekes and Haps) with additional claims for “Oscars”. Three P-38’s went down but the Japanese lost eight fighters with two others damaged. One Zero that failed to return carried Okumura to his death.

The circumstances of Okumura’s loss cannot be known for sure but some American observers saw two or three Zeros low over the ships. At least one of these was apparently flown by a skilled Japanese pilot exploiting the Zero’s strong points. Capt. Charles Adair a fleet staff officer aboard destroyer Conyngham observed “a Japanese fighter, apparently part of their cover, which at 1000 feet cut across in front of our formation chased by a P-38 that was gaining on him and about to open fire. The Japanese pilot kicked hard right rudder and zipped off…The P-38 couldn’t turn that fast and the plane practically disappeared over the horizon!” Possibly that Zero left the fight or possibly once free of its pursuer it re-engaged and was observed a second time. The action report of Destroyer Division Five stated: “One of the highlights of the affair occurred after the end of the destroyer action. All hands were engrossed in watching two P-38’s trying to catch a ZEKE below the clouds. The ZEKE was highly maneuverable, skillfully handled, and evaded the P-38’s time after time much to the amusement of the spectators. The P-38’s finally got him some distance out.” This could be Takeo Okumura’s epitaph.

Okumura was recommended for a two-grade posthumous promotion but in the end was promoted to Warrant Officer, the one-grade promotion normally awarded to personnel dying honorably in combat. The ceremonial sword that Okumura never received was inscribed Buko Batsugun, For Conspicuous Military Valo.