The Japanese air raid on Calcutta, India on December 5, 1943, while perhaps not of immense importance compared to many other events of World War Two, provides interesting perspective on the forces and tactics of the combatants in southeast Asia during the war. In the first half of 1942 the Japanese drove British and Chinese forces out of Britain’s colonial possession Burma (current Myanmar) to the borders of India. During Burma’s rainy or Monsoon season (mid-May through October) air operations were curtailed. Until the closing months of 1942 neither side was able to press vigorous ground operations. Air operations to interfere with the enemy’s lines of communication and attack strong points were conducted by both sides. The Allies (R.A.F. Air Headquarters India and U.S. 10th Air Force) intensified their attacks on Rangoon (Yangon), Burma’s most important port and supply center. In December 1942 with British forces having initiated an offensive from southeastern India toward Akyab (Sittwe) on the coast of Burma the Japanese decided to reciprocate with attacks on Calcutta (Kolkata).

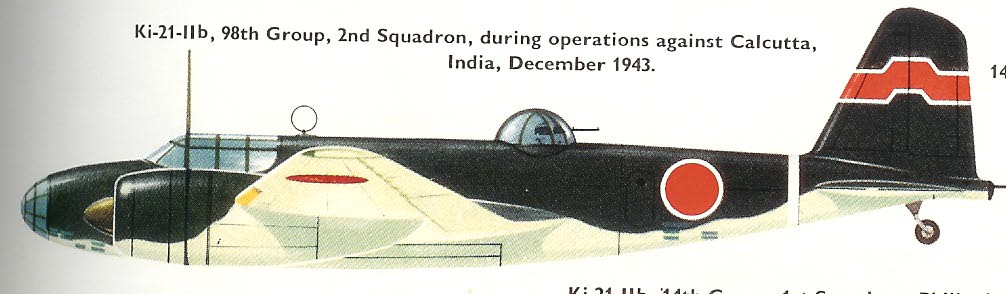

Prologue. On 19 December 1942, Type 97 heavy bombers (Allied codename Sally) from the 14th and 98th Hikosentais (Flying Regiments, FR) transferred from their rear bases in Thailand and Malaya to forward airfields in Burma. The “heavy bombers” were twin-engine aircraft considered medium bombers by the Allies. The twenty or so bombers were dispersed among four different airfields. The first of a series of raids took place late on the 20th. Nine bombers were reported to have dropped 35 bombs. Bombs fell in the Calcutta dock area, at Dum Dum airport and Alipore. There was no interception due to fog and haze. Early on the 22nd an attack by three bombers took place resulting in few casualties and little damage. The attempt at interception was unsuccessful. During the third raid on the night of 22/23 December when three bombers of 14th FR attacked, six Hurricane II’s of R.A.F. 17 Squadron took off to intercept. Two bombers were claimed damaged. One bomber landed at Akyab with an engine shot out and the other crash landed in a paddy field when the gasoline drained out of its damaged fuel tank. In the first three raids it was estimated that twenty-five people had been killed with injured numbering less than a hundred. Damage was generally reported as minor although it included a burst water main, damage to commercial buildings and disruption of some services. On Christmas Eve night fourteen Hurricanes were up to intercept two waves of nine attacking bombers. Three bombers were damaged and one of these was credited as a victory to Wing Commander J.A. O’Neill of 17 Squadron. Accounts differ as to how the raids affected the populace. One news publication assessed civilian morale as excellent. Other reports told of crowded rail stations and a mass exodus of civilians. Newsreel films show both crowds of curious citizens casually surveying bomb damaged buildings as well as large numbers of people moving across a bridge carrying their belongings on their backs or fleeing in horse carts. Service disruptions included uncollected garbage rotting in the streets. Street vendors through which much of the population obtained food temporarily disappeared. Food was an issue in Calcutta since its staple was rice and its main source of rice had been cut off with the Japanese occupation of Burma. An early morning raid on 28 December was not intercepted and reportedly inflicted slight damage and few casualties.

After a hiatus of more than two weeks the raids resumed. Late on the 15th of January three Type 97 bombers of 98th FR were shot down by a Beaufighter of newly arrived No. 176 Squadron flown by Flight Sergeant Arthur Pring. Pring was credited with three previous victories in the Mediterranean theater. Pring was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal and his exploits highlighted in the press along with photographs of the wreckage of one of his victims. On 19-20 January another pilot from 176 Squadron, Flying Officer Charles Crombie R.A.A.F. intercepted four Japanese bombers flying in diamond formation. In an extended action he claimed two as kills and another as a probable victory. His Beaufighter was badly shot up by Japanese gunners, but he and his radar operator escaped by parachute before the flaming aircraft exploded. He had attacked Type 99 light bombers (Lily) of the 8th FR of which one was shot down. Two others returned to base after having engaged in violent maneuvers to avoid Crombie’s attacks. Crombie was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. After these calamities the Japanese suspended attacks on Calcutta.

The December-January engagements confirmed the strength of Calcutta’s aerial defenses. Early warning radar, radar controlled interceptions, and night fighters proved their worth defending a critical target. They also provided important if less positive lessons for the Japanese. They grew in their understanding that the lack of radar in their defense system was a problem that needed to be corrected. They found their bombers’ exhaust flame dampeners were inadequate and needed improvement. Their concern about their bombers susceptibility to fire was heightened. All these concerns were addressed but it took many months to find solutions or partial solutions.

Calcutta: The Target

The introduction to an “Economic Estimate of Calcutta and Environs” in January 1942 provided this assessment:

Calcutta is the premier city of India. It was the original center of British control of India, and today is the commercial, financial, and cultural metropolis. The chief coal, iron, and steel works of India are less than 200 miles away and are directed from Calcutta; while the principal government ordnance factories are just outside the suburbs. Although second to Bombay as a port, Calcutta is the country’s largest railway center. The population of Calcutta is 2,100,000, outnumbering Bombay by some 600,000.

As the war went on Calcutta’s importance grew. Its port and rail network supplemented by motor roads and pipelines supported operations by British XV Corps on the Arakan front and IV Corps centered on Imphal covering the Chindwin River front. It was critical to the buildup of the Chinese Army in India and the aerial supply route from India to China. Calcutta was a transit point for shipping going to the smaller port of Chittagong close to the border with Burma. The many R.A.F. airfields in eastern India were primarily supplied through Calcutta as was the U.S. 10th Air Force.

As 1943 wore on it became evident to the Japanese that the British were likely to renew their offensive in the Arakan where the Allied offensive before the rainy season had been partially rebuffed. Offensive operations elsewhere could not be ruled out. The creation of a new unified command in India, South East Asia Command, on 16 November 1943 reinforced the Japanese conviction that an Allied offensive or offensives were in the offing. The Japanese had offensive plans of their. One was an offensive into India directed at Imphal. This would not only disrupt any plans for an Allied attack on that front but disrupt lines of communications to Allied forces in the Hukawng Valley and bases from which supplies were flown to China. Closer to Calcutta the Japanese planned an attack in Assam both as a spoiling attack and diversion from their main effort farther north.

The Allies had conducted intermittent attacks against Rangoon throughout the rainy season. They intended to increase the tempo of those attacks. This would include R.A.F. bombers attacking at night while U.S. bombers escorted by fighters would carry out daytime attacks. The Japanese began planning an escorted daylight attack of their own – against Calcutta.

An attack on Calcutta seemed feasible because the Japanese army air strength in the area was stronger than it ever had been (or would be again) in late 1943. Moreover, the Japanese naval air force located in Sumatra agreed to join in an attack. Though the combined Japanese air strength was far less than the numbers of Allied aircraft it was strong enough to mount a credible attack. A key issue was having enough fighters to provide safety to the bombers they escorted. The navy’s potential contribution included a balanced force of fighters and bombers.

Attackers and Defenders

Allies. The Allies carried out tactical missions and supply dropping operations along the front lines and into central Burma. For the coming strategic attacks on Rangoon R.A.F. Liberators and Wellingtons would bomb at night while 10th Air Force B-24s and B-25s would bomb by day. They would be escorted by P-38s and newly arrived P-51As. The aerial defense of Calcutta was in the hands of R.A.F. fighters supplemented by British AA guns and a balloon squadron.

Under the recently established R.A.F. Air Command South East Asia, Calcutta’s fighter Defenses consisted of:

221 Fighter Group (Calcutta) – 79 (Hurricane IIc), 136 (Spitfire Vc), 176 (Beaufighter VIf and Hurricane IIc), and 607 (Spitfire Vc) Squadrons.

224 Fighter Group (Chittagong) – 28 (Hurricane IIb) Squadron detachment.

165 Wing (Ramu) – 258 (Hurricane IIc) Squadron.

166 Wing (Chittagong) – 67 (Hurricane IIc), 261 (Hurricane IIc), and 615 (Spitfire Vc) Squadrons.

185 Wing (Feni) – 11 (Hurricane IIc), 60 (Hurricane IIc) and 146 (Hurricane IIc) Squadrons.

Although photo reconnaissance versions of the Spitfire (Marks IV and XI) had long been operational with 681 Squadron, fighter versions of the Spitfire first became operational in early November. Their presence made Japanese reconnaissance over Calcutta more difficult. In November they shot down three Type 100 headquarters reconnaissance planes (Dinah). In October Hurricanes failed to intercept Dinahs despite several attempts. Of the squadrons listed above most participated in the December 5th interception scrambling over one hundred aircraft.

The Spitfire V was active in operations from Britain but was being replaced by the improved Spitfire IX. The Spitfire V first saw overseas service at Malta in 1942 and over Australia beginning in early 1943. The Vc version was armed with two 20mm cannon and four .303 machine guns. It was credited with a maximum speed of 365 m.p.h., had a good climb rate and outperformed German fighters in level turning ability. The Hurricane II was about 30 m.p.h. slower but like the Spitfire was faster than Japanese fighters in a dive. The Hurricane IIc was armed with four 20mm cannon. Both Spitfires and Hurricanes had basic fuel tank protection and pilot armor. The Beaufighter VIf was equipped with radar and operated primarily as a night fighter but was also used in daytime operations. Most pilots in the R.A.F. squadrons were experienced and familiar with conditions along the India-Burma frontier.

Calcutta area airfields along with others farther north were home to strategic bombers of Eastern Air Command. These bombers and newly arrived long range fighters of the 459th Fighter Squadron (P-38’s) and P-51A’s of 530th Fighter Squadron to escort them had the potential to wear down in combat fighters defending Rangoon. These were mainly the same air assets the Japanese were planning to use for the Calcutta attack. If they were weakened the Japanese planning would be nullified. No attack would take place without a strong fighter escort.

Japanese. In November 1943 the Japanese army air strength in Burma was organized in two Flying Brigades (Hikodan), the 4th and 7th under the 5th Flying Division (Hikoshidan). Directly under the division was a reconnaissance unit flying Type 100 headquarters reconnaissance planes (81st FR) and a twin-engine fighter unit (21st FR), both with a dozen or fewer aircraft. The 4th Flying Brigade (FB) consisted of two light bomber units (8th and 34th FR) and two fighter units (33rd and 50th FR) both equipped with Type 1 model II fighters (Oscar). These units carried out attacks prior to the Calcutta raid against Allied airfields from Chittagong to Silchar and Imphal. In addition to their inherent utility Japanese planners hoped these operations would divert British attention and possibly resources from Calcutta. The 7th FB consisted of two heavy bomber units (12th and 98th FR) equipped with Type 97 model II heavy bombers and two fighter units (64th and 204th FR) equipped with Type 1 Model II fighters. Each of the fighter regiments also included a few Type 2 model II fighters (Tojo) specializing in interception missions. The Japanese Type 1 fighter was lightly armed compared to Allied fighters with just two 12.7mm machine guns.

The 64th FR had seen long service in Burma and was among the most famous of Japanese fighter units. Its commander was Maj. Yoshio Hirose famous for being the first Japanese fighter pilot to claim an enemy aircraft in combat (1937). The 50th FR had also seen long service in Burma. In early December it was temporarily between commanding officers. The 33rd FR arrived in Burma in October. Earlier in 1943 it had seen considerable combat in China. Maj. Isao Fukuchi took over when its previous commander was killed in August. The 204th reached Rangoon in November having previously been an operational training unit in Manchuria. Its commander Maj. Hajime Tabuchi had seen combat over the Philippines and China early in the war.

By December 1943 the protective features of the Japanese heavy bombers had been upgraded compared to those used in the Calcutta attacks a year earlier. Their fuel tanks had a thicker protective rubber coating, and they were also equipped with nitrogen injection to reduce the volatility of fumes in the fuel tanks in case of damage. The Type 1 model II fighters coming off the production line since July 1943 had the size (and capacity) of their fuel tanks reduced so they could be covered by thicker rubber coatings. The fighters were slower than the Spitfire but exceptionally maneuverable and gave their best performance at low and medium altitudes.

The Japanese Navy’s contribution to the Calcutta attack came from the 28th Air Flotilla (Kokusentai) newly formed in September. This consisted of Air Groups (Kokutai) 331 (fighters), 551 (carrier attack bombers), 705 (land attack bombers), and 851 (flying boats). Only the fighters and land attack bombers would participate in the attack. Air Group 331 was formed in Japan on 1 July 1943 under flight leader Lt. Cdr. Hideki Shingo. It arrived at its base of Sabang, Sumatra on 17 August and engaged in training and air defense patrols. It sent detachments to outlying locations one being Mergui in southern Burma another was Port Blair in the Andaman Islands. Its 17 November 1943 report stated it had 37 operational Zeros (Zeke) on hand, 28 model 21 and nine model 22. Both types were armed with two 20mm cannon and two 7.7mm machine guns. The Zero was renowned for its long range, good general performance and excellent maneuverability. They lacked any form of protection for the pilot or fuel tanks. Among 39 pilots nine were rated A (suitable for all missions), twelve were B (400+ hours flying time and suitable for all day missions), and eighteen were rated C (full operational training but less than 400 hours flying time). The number of A and B rated pilots had risen substantially since the previous month’s report. Bombers were the Type 1 land attack bomber model 11 (Betty). These were based at Padang engaged in training and sea searches with a detachment at Sabang for sea searches over the Bay of Bengal. These aircraft had rudimentary fuel tank protection provided by an external 5mm rubber sheet attached below the wing integral fuel tanks and a CO2 system. Compared to army bombers little in the way of armor protection was provided for aircrew just two small 5mm plates for the tail gunner. Air Group 705 was a veteran unit that had seen hard service at Rabaul and the Marshall Islands before coming to Sumatra for rebuilding.

In the ten days before the Calcutta attack each side acted both as attacker and defender. Japanese fighters escorted light bombers in attacks on R.A.F. bases at Feni and Argatala clashing with R.A.F. fighters on those occasions with few losses on either side. The Allies for their part initiated a significant campaign against Rangoon area targets by day and night including three major day raids from 25 November to 1 December. Japanese fighters rose in opposition both by day and night. Thanks to a greatly improved warning net incorporating radar they received adequate warning of the incursions. During the day raids the U.S.A.A.F. lost twelve B-24s, eight P-51As and two P-38s with many aircraft damaged. Three R.A.F. Wellingtons failed to return, and two Liberators were lost in crash landings. No daylight raids were mounted against Rangoon for the rest of the year. The Japanese lost only a hand full of fighters in all these operations. Their losses included two Type 2 two-seat fighters (Nick) and one Tojo, types not scheduled to escort the Calcutta bombers. However among the losses 1Lt. Yohei Hinoki, the 64th FR’s leading ace, was injured and had a leg amputated. Early in December Ryu Ichi-go (Operation Dragon-1) was set in motion.

Operation Dragon-1

Preliminary actions to support the attack included gathering stocks of munitions and fuel at the bases from which the attackers would operate. Army aircraft would remain at their dispersed bases until the morning of the attack. Navy aircraft would fly into Tavoy in southern Burma on 3 December and the following day transfer to Magwe which was also the aerial rendezvous point for the attack. As a security measure ground communications were conducted by wire rather than radio. The route was carefully planned to stay several miles offshore as the formations passed the airfields around Chittagong. Two reconnaissance planes of the 81st FR would dispense tinfoil strips meant to interfere with British radar along the attack route. Other recon planes would fly northeast in the direction of Silchar as a feint. Because of the range involved the bomb load of the army bombers was limited to five 100kg bombs. Navy bombers carried two 250kg and four 60kg bombs. The 204th FR would patrol over Magwe the rendezvous base as the attack group assembled. Later they would operate from an airfield on Akyab Island to provide cover for the bombers on the last stage of their return trip.

The Attacking Force. On the morning of the attack the 204th FR was first up to provide security for the attack formation. Bombers from the 12th and 98th FRs headed for Magwe the rendezvous point. Japanese Monograph No. 64, Burma Air Operations Record, 1942-1945, says each Regiment provided nine bombers. This number has been repeated in several publications. However, after the attack an intercepted radio message indicated twenty-seven bombers were involved. This tracks closely with British reports of either twenty-six or twenty-seven twin-engine bombers over the target in the first wave. An article by Japanese historian Yashuo Izawa also gives 27 as the number of bombers. The bombers were joined by seventy-six escorting fighters according to the same message (Monograph No. 64 says 74 fighters). At 1120 they set off flying at 1000m (about 3,300 ft.) on a due west course. The 33rd FR provided forward cover the 64th top cover and the 50th flew above and behind the bombers. Per plan the navy contingent was to be twenty minutes behind but eventually they lagged by twice that amount of time. Navy bombers were led by Lt (j.g.) Takazumi Iijima. Prior to reaching the target six army fighters and one navy bomber aborted the mission.

Time zones are tricky in this story switching between a 3 and 2-½ hour offset. The time kept by the Japanese was JST (+9 GMT). Burma and parts of India were +6-½ and other parts of India +6. For example the British version of the attack has bombs falling at 1147 hours and the Japanese at 1417. An 1120 departure was probably 0850 at the closest British radar stations.

En route interception. The R.A.F.’s first indication of enemy activity was a radar contact with an unidentified aircraft presumed to be hostile 95 miles northeast of Chittagong flying at 28,000 feet at 0925 hours. Another was plotted 30 miles east of Comilla about twenty-five minutes later and later disappeared. These were likely diversionary flights of 81st FR recon aircraft. Soon after the first plot another presumed hostile single aircraft was plotted 70 miles west of Akyab. It was plotted on a westerly heading before being lost to tracking. It was not only Japanese aircraft flying offensive missions that morning. A dozen Vengeance dive bombers of 110 Squadron were sent against a Japanese camp on the Arakan front. Eleven returned without bombing due to weather. One pilot thought he found and hit the camp.

The first interceptors, a dozen Spitfires of 136 Squadron, scrambled at 0925. They were followed by additional Spitfires 615 Squadron (12) at 0945 and 607 Squadron (13) at 0950. Also at 0950 the first of twenty-eight Hurricanes from four squadrons scrambled. All these fighters were based on airfields in the Chittagong – Cox’s Bazaar area.

It is tempting to speculate that accustomed to attacks on airfields in their own area some of squadrons may not have flown away from the coast as expeditiously as they might have. In any event many squadrons only sighted the Japanese mass formation at a distance and failed to engage. Flt. Lt. Eric Brown of 136 Squadron pressed on to the mass formation reported as forty aircraft when many of his mates had turned back due to fuel considerations. He fired on a bomber that he claimed as destroyed. Returning from the combat his Spitfire ran out of fuel, and he survived a crash on Sandwip Island. Hurricanes of 258 Squadron also managed to engage. W/O Peter Hicks of 258 Squadron sighted a lone Type 97 bomber (possibly the bomber engaged by Brown) and dove on the bomber closing to 200 yards to open fire. Hicks reported inflicting damage before being driven off by a Japanese fighter. Over the radio he heard Flt. Lt. Arthur Brown the Canadian 258 Squadron flight leader stating he was engaged. Arthur Brown failed to return. Sgt. Toshio Miyabe and Lt. Kiyotake Nakashima’s section of the 50th FR chased the two British attackers away. W/O Norio Shinoda of the 64th FR claimed a Spitfire en route to the target. This might have been a misidentification of a Hurricane or wishful thinking after a brush with Eric Brown or another Spitfire. A 98th FR bomber flown by Lt. Kenjiro Nishimori failed to return from this encounter and another bomber was damaged. The Spitfire and Hurricane had certain positive qualities. Long range was not one of them. The Japanese fighters did not jettison their long range tanks and continued the mission.

Interception over the target and after. At 1243 JST the Japanese formation now flying at 3000m (10,000 ft.) changed course to a northeast heading and began a climb to attack altitude. They were soon picked by Calcutta radar but not immediately recognized as a threat. Once it seemed Calcutta might be their target local fighter squadrons were alerted. The first interceptors, four Hurricanes of 176 Squadron, were scrambled at 1039/1309. The 176 Squadron Hurricanes were specially modified stripped of armor and other excess weight but with air intercept radar added. Soon after taking off they were ordered to land. The Japanese formation reached attack altitude of 7000m (23,000 ft.) shortly after 1330. A dozen 67 Squadron Hurricanes scrambled at 1050 hours. They were followed by thirty-two other Hurricanes and four Beaufighters. A week earlier Calcutta had been defended by Spitfires, but they had all moved to forward area airfields prior to the raid.

Twenty Hurricanes of 67 and 146 Squadrons joined up and climbed to 27,000 feet. About thirty miles from the target they caught sight of the bombers flying in three large V-formations. They estimated the bombers’ altitude as 25,000 feet with their fighter escort higher. The 67 Squadron Hurricanes led the way with an attack on the bombers followed by 146 behind and a little lower. Fighters of the 33rd and 64th FRs dove in to cut them off from the bombers. F/O Gordon Williams of 67 Squadron was the only pilot to claim a victory, an Oscar. He also damaged another fighter. Three other 67 pilots claimed damage. W/O Aubrey Bond was shot down and killed in the crash. Two other pilots rode their damaged Hurricanes down to crash landings.

P/O D.W. Blackmore of 146 Squadron got in a shot at a Japanese bomber before being forced out the fight by three Oscars. Sgt. N.M. Dawber claimed a probable Oscar. The Japanese fighters stymied other attempts to engage the bombers. One 146 pilot bailed out, another crash landed and a third returned in a battle damaged Hurricane. Pilots of the 64th FR claimed four certain victories and two uncertain. Total Japanese claims in actions against 67 and 146 Squadrons were eight and two uncertain.

The balance of the Hurricanes as well as the Beaufighters were unable to intercept the first wave of raiders but were directed to the lagging navy formation. Flt. Lt. David Brocklehurst flying his second mission of the day led Hurricane (AI) IIc’s of 176 Squadron catching the Japanese formation about sixty miles southeast of Calcutta as it withdrew. Among the pilots in this flight was F/O Maurice Pring hero of the night defense of Calcutta a year earlier. The Hurricanes never got to the bombers. Zeros dove on them from above. Two pilots including Pring were killed. A third pilot was shot down but survived. Brocklehurst returned in a bullet riddled Hurricane. No Japanese aircraft were lost. Pilots of Air Group 331 claimed four Hurricanes certain and two uncertain. Four returning bombers had been hit by enemy fire and one crewman was slightly injured, but this likely was caused by anti-aircraft fire. Ground gunners claimed one bomber probably destroyed and three damaged.

During the withdrawal twenty-four Spitfires (607 and 615 Squadrons) were scrambled to intercept the returning Japanese formation. They failed to make contact. The last act of the air combat came when six 261 Squadron Hurricanes flew to Akyab suspected as the base from which the Japanese operated. They were met by Type 1 fighters of the 204th FR. The Hurricanes claimed a probable and a damaged. One Hurricane hit by Japanese fire returned and landed with a bullet damaged tire. It ended up off the runway in the rough with the pilot suffering minor injuries.

The final result of the air combat was the Japanese loss of only one bomber. One 50th FR Type 1 fighter flown by Cpl. T. Maekawa that was initially believed lost landed at an airfield on Akyab Island low on fuel. The pilot and aircraft rejoined their unit. The box score given in an Allied intelligence summary shortly after the attack reported enemy losses as one twin-engine and one single-engine destroyed, one twin-engine and two single-engine probable, and five single-engine damaged. Allied fighter losses were reported as five missing, five crashed, and one damaged. Even without including Eric Brown’s Spitfire or the Hurricane pranged after the Akyab action information available soon after the attack made it clear that results of the air battle favored the Japanese. That left open the question how much damage the bombing inflicted and was their effort worth it.

Effects of the attack. A description of the raid’s impact was contained in a weekly intelligence summary issued by South East Asia and India Command. Other contemporaneous reports provide essentially the same information. The substance of that W.I.S. has been repeated in a variety of official histories and other publications over the years. According to the Summary the attack on the Kidderpore docks came in two waves an hour apart. Eighty-six high explosive and anti-personnel bombs were dropped one of which was a thousand pounds and three of which were unexploded. Nine sheds were hit of which two were gutted. Three motor vessels and a Royal Indian Navy vessel sustained superficial damage. A floating crane was damaged, and fifteen barges set afire. Considerable damage was done at a balloon site. British military casualties were four killed and thirty-three wounded. U.S. forces lost one killed and twenty-five wounded. Civilian casualties reported as of the evening of 6 December were 483. All labor left the dock area. As of 7 December only about 10% of the normal 4/5,000 workers were on hand. Some work was being undertaken by military personnel.

A report from the U.S. liaison office in Calcutta on 6 December provided some additional details. The most serious aspect was the effect on dock labor. Loading and unloading was at a standstill. Stevedores and skilled labor are on the job but coolies fled the city. Chairman of the Port Commission believed coolies would return in 2 or 3 days. Bombs were said to be mostly anti-personnel and incendiary of one to two hundred pounds. In addition to twenty-six Army casualties four U.S. Navy seamen suffered shrapnel wounds.

These reports while essentially accurate fail to capture all the details of damage and do not reflect raid’s most important effect. Trucks in a truck convoy in the dock area were damaged by the bombs. Rail lines were cut. U.S. LST-176 was in drydock when the bombs from the first wave fell about a mile away. In the second wave bombs fell close to the ship and one seaman was wounded by shrapnel. This Navy casualty was in addition to the four mentioned in other reports. In addition to casualties at the balloon site six balloons and a hydrogen generation plant were destroyed. Although morale of the general populace was reported as good workers at a Jute factory 400 yards from the bombing all left the area. Ten days after the attack only about half the labor force had returned and dock operations were about 2/3 normal and slowly improving. The Indian government announced civilian casualties as 167 killed and 435 injured.

One interesting data point is that the British Admiralty shipping casualty section determined that rather than three cargo ships slightly damaged, eight had been damaged in varying degrees. All remained afloat and none was deemed seriously damaged. Six of these ships were British, one American and one registered in Panama. The nature of the damage these ship received is unclear but there are indications it was not minor in all cases. Casualties aboard these ships included four officers wounded with one crew member killed and sixteen wounded. The war diary of LST-176 recorded that one cargo ship received a direct bomb hit and injured members of her crew were treated by the surgeon from LST-17. The one U.S. vessel Liberty Ship S.S. William Whipple had been damaged to the extent that she was unable to sail with convoy C.J. 8 on 9 December as scheduled.

The most profound effect of the attack was the disruption to cargo flowing to fighting fronts. For the entire month cargo moving through Calcutta was 1/3 less than normal. Supplies for the U.S. Army were 15,000 tons less than projected. This level of reduction might have been sustained by additional Japanese attacks. If so the ability of the Americans to conduct offensive operations in north Burma and maintain adequate supplies by air to China would have been seriously compromised. The Japanese elected not to repeat the attack in December 1943 or in January 1944. Thereafter the diversion of available Army and Navy air assets to other fronts rendered them unable to undertake such an ambitious effort.