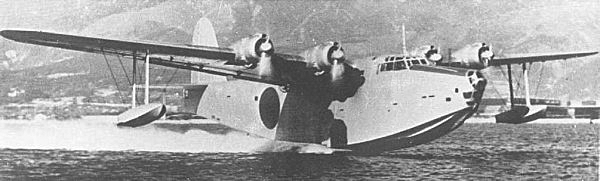

On February 5, 1942, a routine Japanese administrative order was issued: “13 Experimental large model Flying Boat is adopted and designated Type 2 large Flying Boat, model 11.” Administrative Ordnance Order (Naireihei) No. 8-42. The Shi 13 experimental aircraft was accepted for operational use and serial production. The first production aircraft had not come off the Kawanishi line, but two prototype aircraft at the Yokosuka test center were available for use.

Prototype of Type 2 flying boat

A little over a month later The U.S. Chief of Naval Operations summary of “Japanese Naval Activities” for March 7, 1942, stated:

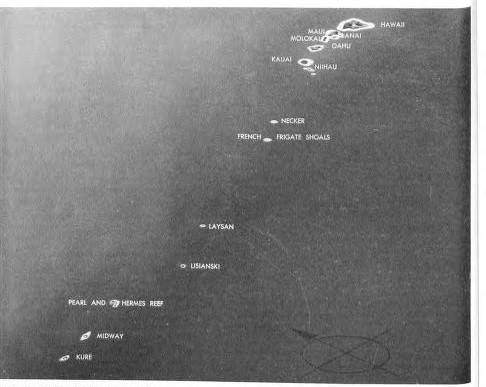

The Yokohama and Chitose Air Groups, totaling about 20-24 flying boats (VPB) are at Wotje, Marshall Islands…Close radio association between those air groups and three submarines reported in an area French Frigate Shoals – Midway suggests a practicable plan for raids on the Hawaiian Islands by which attacking planes are serviced from submarines in the above area in sheltered water after flying direct from Wotje and before attacking objectives. In this manner the attacking planes could be loaded to capacity shortly before the raid and thereafter make the return flight of 2,000 miles non-stop under light load conditions.

The information provided in the CNO’s intelligence summary contains a remarkably accurate description of Japanese plans. It also contains some interesting errors. Chitose Air Group (Kokutai) was equipped with medium bombers. This was well known to U.S. intelligence and was probably an administrative error. Yokohama Ku had detachments at Rabaul, Greenwich Island and in the Marshall Islands where its main base was at Jaluit atoll. Moreover, as of the date of the summary one attack had already been carried out, one cancelled, and additional reconnaissance missions following the pattern outlined would be forthcoming in the immediate future.

As will be seen, the Japanese administrative order and high level American intelligence summary were related. While the Japanese were taking advantage of Allied unpreparedness in the Philippines, Malaya, and the Netherlands East Indies they understood that the American Pacific Fleet with its aircraft carriers and remaining heavy warships posed a continuing threat that needed to be observed by radio and physical surveillance.

Midway to Hawaii

Submarine Reconnaissance

In addition to the massive air attack launched from six aircraft carriers the Japanese Hawaiian operation on December 7, 1941, involved submarines. Five submarine mother ships carried five two-man subs intended to penetrate Pearl Harbor during the air attack. Only one made it into the harbor and caused no damage. All five were lost. After the attack Japanese submarines remained in Hawaiian waters to observe ship movements and attack targets of opportunity.

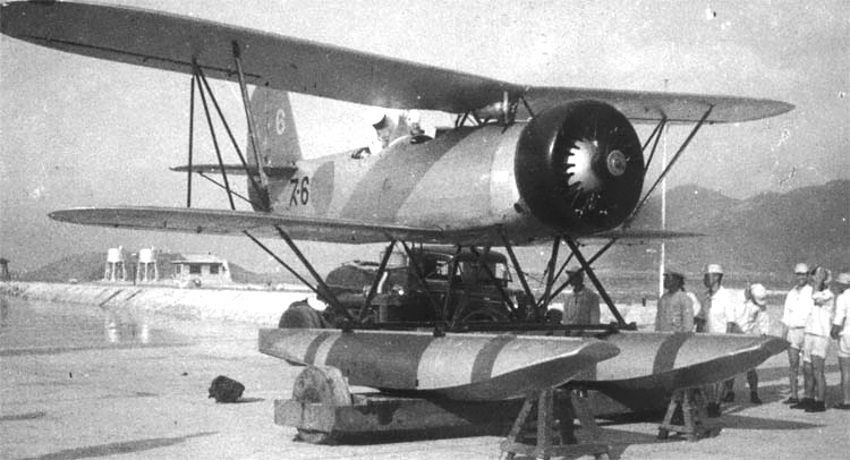

Ten days after the attack an aerial reconnaissance of the harbor was conducted by an aircraft launched from a submarine. Submarine I-7 launched a Type 96 small reconnaissance seaplane for a dawn reconnaissance. I-7 carried an aircraft hanger on its rear deck. Due to light wind conditions the submarine had to assist the catapult take off by powering into the wind. This it did in reverse launching the little biplane over its stern. Petty Officers Mitsunobu Kaga and Murao Okamoto reached Pearl Harbor and made observations without being recognized as an enemy intruder. They landed on return but abandoned their aircraft after landing and swam to the sub. The aircraft was scuttled but they reported on shipping in the harbor and the state of repair activities. On January 4th a nighttime reconnaissance by I-19’s seaplane was accomplished despite technical difficulties and intrusion by an American patrol vessel. These operations may have convinced Tokyo a night attack on Pearl Harbor was feasible.

Type 96 small recon seaplane

The next aerial reconnaissance attempt from a submarine came on February 24, 1942. I-9 launched another Type 96 small seaplane. On this occasion darkness and foul weather resulted in no useful information being obtained nor was there any indication the aircraft was detected. On return the aircraft was damaged while being recovered.

Operation K – First Phase

Barely a week after the issuance of Ordnance Order No. 8-42 two H8K1 pre-production large flying boats having completed their test program were on their way from Yokosuka to the Marshall Islands. Operating from Wotje Island they practiced refueling at sea and flew short range missions. This was in preparation for Operation K an ultra-long range mission to bomb Pearl Harbor. Hosted by the resident air group Yokohama Ku the two aircraft came under the command of the 24th Air Flotilla (Koku Sentai). Before leaving Yokosuka Lt. Yoshio Hashizume was selected as mission commander. Mission preliminaries included submarines I-9 and I-23 maintaining surveillance in the waters near Pearl Harbor. The flight of I-9’s reconnaissance plane was part of the Operation K mission plan. I-23 was equipped with a hanger but did not have an aircraft embarked. It contacted base by radio on the day of the I-9’s aerial reconnaissance but was not heard from thereafter. Cause of loss is unknown.

The idea of a flying boat attack on Pearl Harbor originated in Tokyo in mid-January 1942 with the 4th Fleet and 24th Air Flotilla directed to begin planning advising two “Type 13 (new type long range) patrol planes” would be assigned. By the last week in January 1942 consultations between Combined Fleet and 24th Air Flotilla set the second of March as the target date. In late January, while returning from operations in the Hawaii area submarine I-22 was tasked with finding a possible refueling site in the vicinity of Midway and Hawaii. Upon return to Japan in early February her captain reported the French Frigate Shoals atoll between Midway and Oahu was suitable. Detailed plans for a second attack on Pearl Harbor rapidly fell into place.

Navigation assistance was provided by relocation of I-9 between the objective and the Marshall Islands to transmit a directional signal. Submarines with their hanger space modified to carry a large fuel load (I-15 and I-19 with I-26 in reserve) were sent to French Frigate Shoals. Weather reports became an issue. The U.S. changed its code for weather reports which the Japanese had previously been able to read just before the operation. As a substitute weather from Wake Island was monitored and a Type 97 large flying boat was sent out ahead of the mission to 700 miles to report on weather en route. With I-23 silent, weather reports in the vicinity of Oahu were not available. Refueling submarines found conditions at French Frigate Shoals good. The mission went forward a few days after the initial target date.

In the first hour of 4 March 1942 (Japan time) the two flying boats took off from Wotje. They were reportedly numbered Y-1 and Y-2; Y-1 captained by Lt. Yoshio Hashizume and Y-2 was piloted by Ens. Shosuke Sasao. The planes were loaded with gasoline and four 250kg bombs each. With the help of I-9’s radio beacon they arrived over French Frigate Shoals in the early afternoon landing after their fueling submarines were ready. Waves were choppy in the protected lagoon but refueling was successfully accomplished. In mid-afternoon the heavily laden aircraft took off for the 560 sea-mile flight to their objective. Reaching Oahu, first way point being the Kaena Point lighthouse, they encountered dense clouds which made accurate observation of the harbor impossible. The planes became separated with one heading north and the other south. Their specific objective was the “long dock” in Pearl Harbor where large ships were likely to be located. Both aircraft eventually released their bombs blindly based on their estimated positions, falling in one case into the sea and in the other between Kaneohe and Honolulu.

Modern Honolulu

From the American side was an intelligence assessment reported to Pacific Fleet headquarters at mid-morning 4 March (Hawaii time) that there are indications of an impending attack by enemy submarines and aircraft on 4 or 5 March. Radar on Kauai picked up a bogey 90 miles to the northwest. Subsequent radar plots tracked the target to Kaena Point then around the north coast of Oahu until opposite Kanohe where it turned toward Honolulu. The Condition I alert resulted in electric lights being extinguished. When the planes were over Oahu the only lights seen were AA searchlights searching the sky. No AA was fired.

The U.S. Navy’s record of events was described in the Pacific Fleet war diary:

0014 – Army radar on Kauai picked up unidentified aircraft plot bearing 290 deg. T, distance 204 miles from Oahu. Succeeding reports tracked this or these unidentified aircraft to Oahu and later away from Oahu in a southwesterly direction. Last radar report at 0316 indicated aircraft bearing 235 deg. T, distance 130 miles from Oahu, heading southwest.

0043 – Initial air striking groups were ordered by Compatwing Two, 3 patrol planes taking off at 0115 armed with torpedoes. Four Army pursuit planes took off at 0136.

0048 – [Com 14 ordered all ships to general quarters – Army order at 0159].

0210 – Three explosions were heard in vicinity of Tantalus. Army later reported evidence of 3 or 4 bombs of 300 to 600 lbs. size dropped in that vicinity. Investigation indicates…tracked from the northwest…probably did drop these bombs.

0342 – Com 14 directed all commands to assume normal condition…At this time Army planes landed, and 3 Navy patrol planes remained in the air.

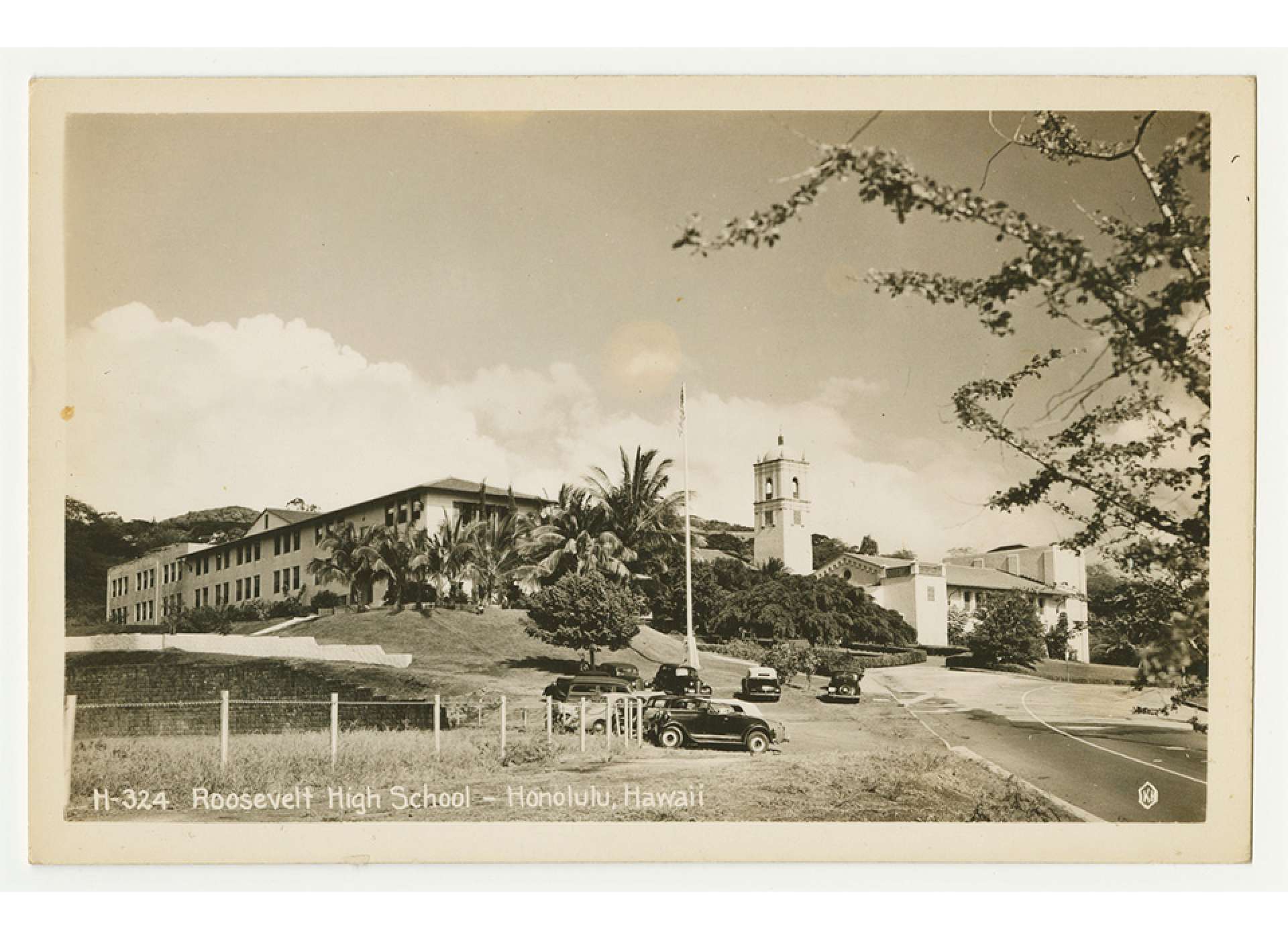

Sasao’s bombs fell in the sea. Hashizume’s bombs fell on Tantalus Mountain east of Honolulu. They created substantial craters. Later investigation revealed they were the same type of bombs dropped in the December 7 attack. The bombs hit about three hundred yards from Theodore Roosevelt High School where the primary damage was some shattered window glass. There was some confusion after the attack about the cause of the alert and bomb craters. The public was not fully informed. Even with the intelligence data available, not all military authorities were aware of what had occurred. A wealth of intelligence primarily derived from radio intercepts was available but as with the original attack neither advance intelligence nor current radar information resulted in a fulsome defensive response. The C.N.O. Intelligence summary quoted above suggests that while Washington was aware of warnings derived from signals intelligence the facts of what had happened more than a day previously had not penetrated to that level and been analyzed.

The two flying boats began their long return trip of nearly 2,000 nautical miles. Hashizume discovered the hull of his aircraft had been damaged on take-off at French Frigate Shoals and opted to return to Emidje (Ebeye), Jaluit atoll where Yokohama Ku had its primary base and repair facilities in the Marshalls. Sasao returned to Wotje as planned. Both arrived safely after spending more than thirty hours in the air over two days.

Operation K – Follow Up

A second Operation K attack on Pearl Harbor was scheduled for the seventh of March. It was cancelled. The refueling submarines were recalled to Japan after being diverted to attempt an interception of the American task force that raided Marcus Island. Also the destroyer U.S.S. Ballard visited French Frigate Shoals having been sent there based on intelligence about the presence of Japanese submarines. No submarines were found and inexplicably a shore party destroyed barrels of water stored for survivors of any disaster that might reach the atoll.

With the second Hawaii strike cancelled Japanese Combined Fleet headquarters tasked Yokohama Ku with sending the two aircraft on separate reconnaissance missions to Midway and Johnston Islands. The distances involved though very long, about three-quarters of the distance to Hawaii, did not require refueling. Midway had been a stop on Pan American Airlines Clipper service across the Pacific. It supported a naval base and airfield. Johnston Island had been developed as a Navy seaplane base in the mid-1930’s and more recently an airfield had been constructed on reclaimed land there. Both locations had been briefly shelled by Japanese submarines soon after the outbreak of hostilities.

At Midway Marine Air Group 22 was organized on March 1, 1942, incorporating the existing Marine air detachment of a fighter and dive bomber squadron. VMF-221 had been at Midway since January. With the organization of VMF-222 the two squadrons initially shared the available aircraft and personnel: thirteen Brewster F2A-3 fighters and nineteen pilots. The two squadrons operated as an integrated unit pending the arrival of additional fighters and pilots. Johnston Island had no resident fighter squadron.

Hashizume was assigned Midway and Sasao Johnston. Their flying boats were relatively well armed. Dorsal and tail turrets housed 20mm cannon. A nose turret and side blisters mounted machine guns. A 7.7mm machine gun could also be stationed at a ventral hatch located approximately below the leading edge of the vertical tail. That position was apparently manned for this mission. Sasao got to Johnston circled the atoll without opposition and returned with valuable information. Hashizume failed to return.

On 6 March COM 14 (command element of Naval District 14 in Hawaii) had warned that air raids might be expected on “this front” for the next ten days. Three days later this was followed by a warning of the possibility of attack by flying boats tonight or tomorrow on Palmyra, Johnston or Midway.

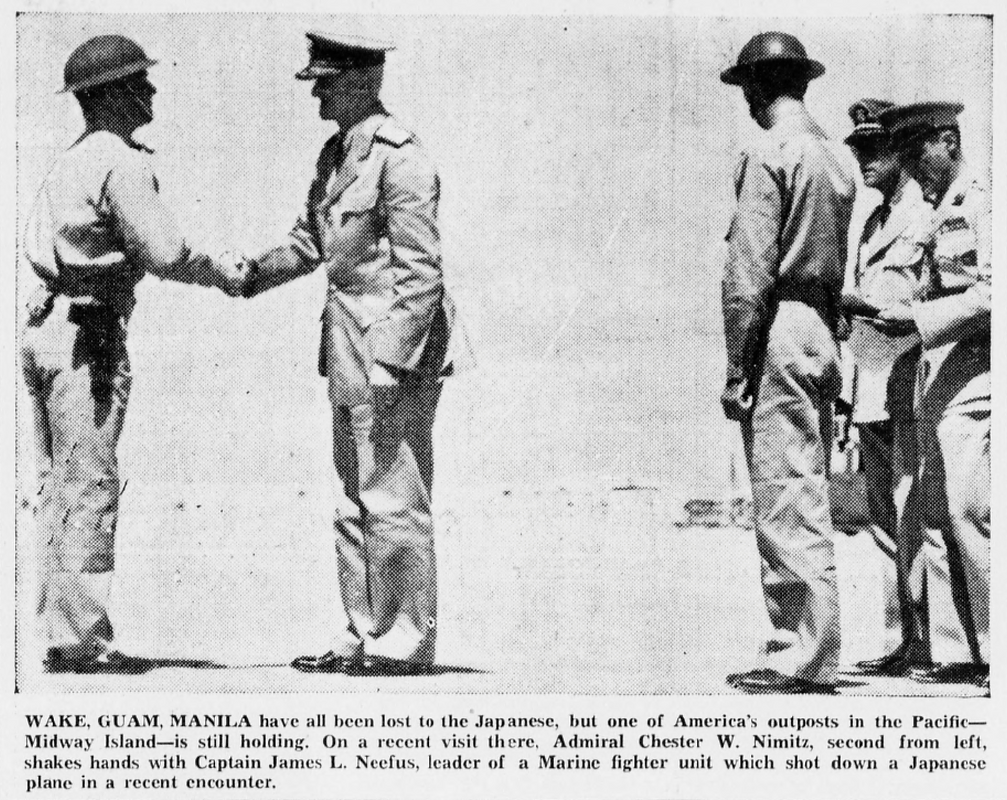

At mid-morning on March tenth Midway radar picked up a bogey approaching from the west at 43 miles distance. Within minutes an air raid warning went out and Marine aircraft were scrambled to avoid being caught on the ground. Nine F2As and sixteen SB2Us were aloft within ten minutes of the warning. One division of four fighters under Capt. John Dobbin already aloft was directed to fly 275 degrees out 25 miles. Lt. Col. William Wallace recently appointed to command MAG-22 but previously commander of Midway’s Marine Air Detachment supervised and directed fighter control. Two other four-plane tactical formations under Capt. Robert Haynes and Capt. James Neefus were directed 280 degrees, 25 miles at 8,000 feet. The bogey was cagey changing course several times including moving away from Midway out to seventy miles distance. About twenty minutes after initial contact the bogey began closing the distance toward Midway from fifty miles out at an estimated altitude of 7,000 feet.

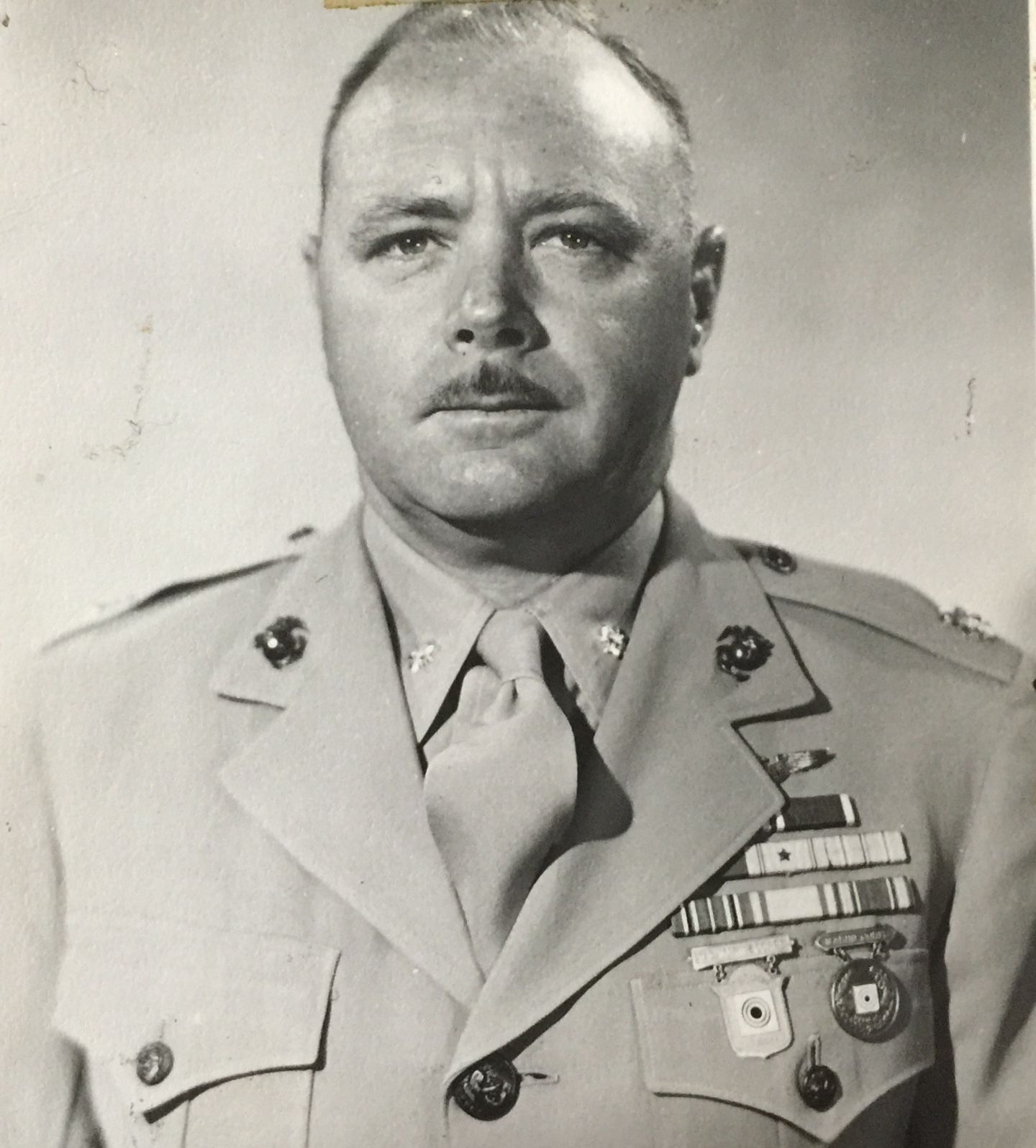

Col. James Neefus

Wallace directed the flight led by Capt. Neefus to intercept. His wingman was 2Lt. Francis McCarthy. The second element consisted of 1Lt. Charles Somers and Marine Gunner Robert Dickey. All four pilots were assigned to VMF-221. Less than ten minutes after being directed to intercept Neefus sighted Hashizume’s flying boat five miles distant at 9,000 feet. Hashizume likewise sighted the fighters and turned to run away. At full throttle the Buffaloes could only slowly close the distance. Once the fighters closed to within range Hashizume put his big aircraft into a dive of about 30-degrees. Neefus carried out a high side approach consistent with Navy/Marine tactical doctrine followed by his wingman. Hashizume’s high speed and dive made a set piece attack difficult, but element leader Somers carried out a modified high side pass. Dickey had fallen behind and made a pass from astern. Dickey’s fighter was hit by several 7.7mm rounds. A couple hit the engine and one broke Dickey’s left arm. He headed for base unable to use his left (throttle) hand.

Col. Dickey

The flying boat disappeared in a cloud bank. Neefus waited for his opponent to break clear. When that failed to happen he dove beneath the clouds and saw smoke and flames on the water marking the spot where large flying boat Y-1 had crashed. Despite his wounds and damage to his fighter, Dickey successfully returned to Midway as did the other members of the division. Neefus received the Navy Cross. The other members of the flight were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, Dickey in the hospital at San Diego. He was later commissioned and served a full career in the Marine Corps. Two enlisted men manning the radar were given commendations and promoted. Neefus became CO of VMF-221 in April but was reassigned prior to the Battle of Midway.

Neefus and Nimitz

After the Ultra-long Range Missions

The Type 2 large flying boat proved its worth in its initial operations. On the first of April 1942 the 14th Kokutai was formed to operate Type 2 large flying boats. Production proved to be very slow but by mid-April the first missions were being flown from Marshall Island bases. Initially just one or two aircraft per day flew search missions. By the end of the month up to four aircraft were in use. With prospects of reaching full strength of twelve aircraft months in the future the first Type 97 large flying boat was added to the air group on an interim basis. In July two Type 2 flying boats were attached to the 25th Air Flotilla at Rabaul. They resumed long range attack mission in late July and early August by attacking targets in Australia Horn Island, Townsville and Cairns.

In 1943 the improved model 12, Type 2 large flying boat was introduced and gave good service albeit in relatively small numbers until the end of the war.

Several months after the events chronicled in this article Allied code names were assigned to Japanese aircraft including those mentioned. Type 96 small reconnaissance seaplane – Slim; Type 97 large flying boat – Mavis; Type 2 large flying boat – Emily. In none of the primary source material reviewed for this article were manufacturer’s model type designations (E9W1, H6K2, H8K1) used.