On the first of August 1943, PT-109 was rammed and cut in two by a Japanese destroyer. The story from the American perspective is well known because the skipper of PT-109 was future President of the U.S. John Fitzgerald Kennedy. The following excerpt from South Pacific Air War shines additional light on the subject from the Japanese perspective. South Pacific Air War also shows that Japanese air action by night flying floatplanes greatly reduced the effectiveness of American PT-boats in the Solomons campaign. I’ll leave it to you to decide who “The Real Hero” was on 1 August, 1943.

The first day of August brought a resurgence of Japanese daytime air action, after a hiatus of several days. In the morning, two strikes, one by a single dive bomber and two escorting Zeros and a second by six dive bombers with 39 escorting fighters, struck targets near Rendova and Roviana Lagoon. The dive bombers claimed a transport and a destroyer sunk, but their bombs, while close to a destroyer, made no hits. They also claimed some ground damage. Zeros strafed landing craft. A Ryuho dive bomber was shot down by AA fire and crashed at Liana Beach. The wreckage of Type 99 carrier bomber No. 3134 was found. The Japanese were concerned because it carried code book Rei 15 which might have been captured. A TBF spotter plane and a Japanese dive bomber exchanged fire during these operations.

Near the end of the day, the Japanese launched a strike with nine dive bombers and twenty fighters as close escort. The fighters ran afoul of P-40’s of the 44th FS returning from escorting SBD’s to Bougainville. Six of the P-40s dropped below a cloud layer where they encountered Zeros of Air Groups 201 and 251. The P-40’s claimed a Zero and lost one Warhawk with its pilot, 1Lt. Ralph Imberg. Another P-40 crash landed at Segi, a third P-40 was badly damaged, and a fourth took twenty-seven 7.7mm hits and had an aileron shot off. Two of the pilots were slightly injured. The Zeros claimed five P-40s. Three Zeros were hit; one made an emergency landing. AA claimed several dive bombers but only one was lost.

The dive bombers hit the Lombari Island PT-boat base. PT-117 and -164 were destroyed and a third damaged. Two men were killed. Despite the loss of these PT’s, fifteen others were able to go on nocturnal patrols to counter expected Japanese reinforcement activities. This resulted in the last clash of PT-boats and Japanese destroyers of the campaign.

Down from Rabaul, on their way to Vila, were three Japanese destroyers transporting troops and supplies, plus escort Amagiri. The PT-boats operated in three groups of four and a fourth group of three boats. The first group made radar contact, about midnight, with ships heading south close to the Kolombangara coast. When visual contact was made, the four ships were at first thought to be large MLCs, but when they opened fire with heavy weapons their true nature became evident. Two of the PT’s managed to launch torpedoes before the action was broken off. A large explosion was reported as the only potentially positive result of the action. Two other PT-boats including PT-109 failed to launch torpedoes.

From the next group to engage, one PT launched its torpedoes but crossed in front of three other boats and fouled their approach. The destroyers fired star shells and their heavy weapons. Two boats were straddled by their fire. Three PT’s turned north and then returned to their patrol area where they reported being attacked by four float planes that dropped flares and bombs but caused no damage.

In the third group, only one PT-boat was radar equipped, it rushed ahead to attack, firing its torpedoes by radar and then returned to base. Another boat also launched torpedoes, was ineffectively strafed by a floatplane and returned to base. A third PT discharged torpedoes from two miles range and returned to base without observing any result. The fourth boat did not make contact. Two PT-boats of the fourth group fired torpedoes at long range without observing positive results.

Japanese Destroyer Amagiri

After arriving offshore from Vila, Amagiri kept watch. Hagikaze, Arashi, and Shigure drifted, while nine hundred troops and 120 tons of supplies were transferred to MLCs. Offloading took less than half an hour. Mission accomplished; the four destroyers headed north. Several PT-boats were still on station along the way but the few torpedoes that were fired, all missed. The Japanese apparently did not observe these attacks.

To the north, a trio of boats – PT-109, Lt. (j.g.) John Kennedy, leading PT-162 and PT-169 – was the only force left in position to inflict damage on the Japanese. The story of the future President and PT-109 has been related in books, articles and a movie. Kennedy is portrayed as a hero of the action. From the contemporaneous Japanese perspective, the hero of the action was Lt. Cdr. Kohei. The story first appeared in the 4 August 1943 number of Nippon Times, Nippon Destroyer Rams Foe Warship. A month later, a more detailed account of the action, characterized as a Feat Unparalleled in Annals of Naval History, was published. After the fact, some Japanese questioned the story, but contemporaneous accounts were confirmed by the key participants years later. The Japanese story starts by recounting the approach. In the story the first two PT-boat sections are compressed into an encounter with six torpedo boats in which two were reportedly sunk, another damaged, with the survivors fled in disorder. The PT-boats of the third and fourth groups are not mentioned, probably because the Japanese destroyers did not become aware of their attacks or even their presence.

Despite a dark night, narrow passage and dangerous reefs and shoals, the four destroyers headed for home at high-speed. Per the press account:

[A] lookout barked out, “Torpedo boat forward off port.” Simultaneously the commander…and others on the bridge saw three black shadows about to cross their bow and head for the comrade ships. They were XX meters off. There was no time for gun action. If the enemy should release torpedoes against the unaware comrade ships, they would have no chance. The commander made up his mind – “Charge!” This order, probably never before given in modern naval warfare, was made. The helm turned hard a-starboard, and the destroyer plowed full speed into the nearest torpedo boat.[1]

The story goes on to describe the jolt felt by those aboard the destroyer, the flaming wreckage of the two halves of the torpedo boat and other details. Contrary to some American accounts, the story asserts Amagiri was not slowed down by the ramming. Whatever damage was suffered, she was in action on a supply run to Tuluvu in western New Britain two days later. Lt. Cdr. Kohei was quoted as saying: “I was very happy that we were able to crash into the enemy torpedo boat before its torpedoes were fired and there was no damage to our comrade ships.” Long after the fact, the division commander on Amagiri’s bridge along with Kohei, asserted that the collision was merely an accident not intentional. Whether this was his true impression or merely sour grapes at his subordinate’s actions outshining his own is hard to determine. The overall success of the mission might have been credited to the division commander but was publicly portrayed in a different manner.

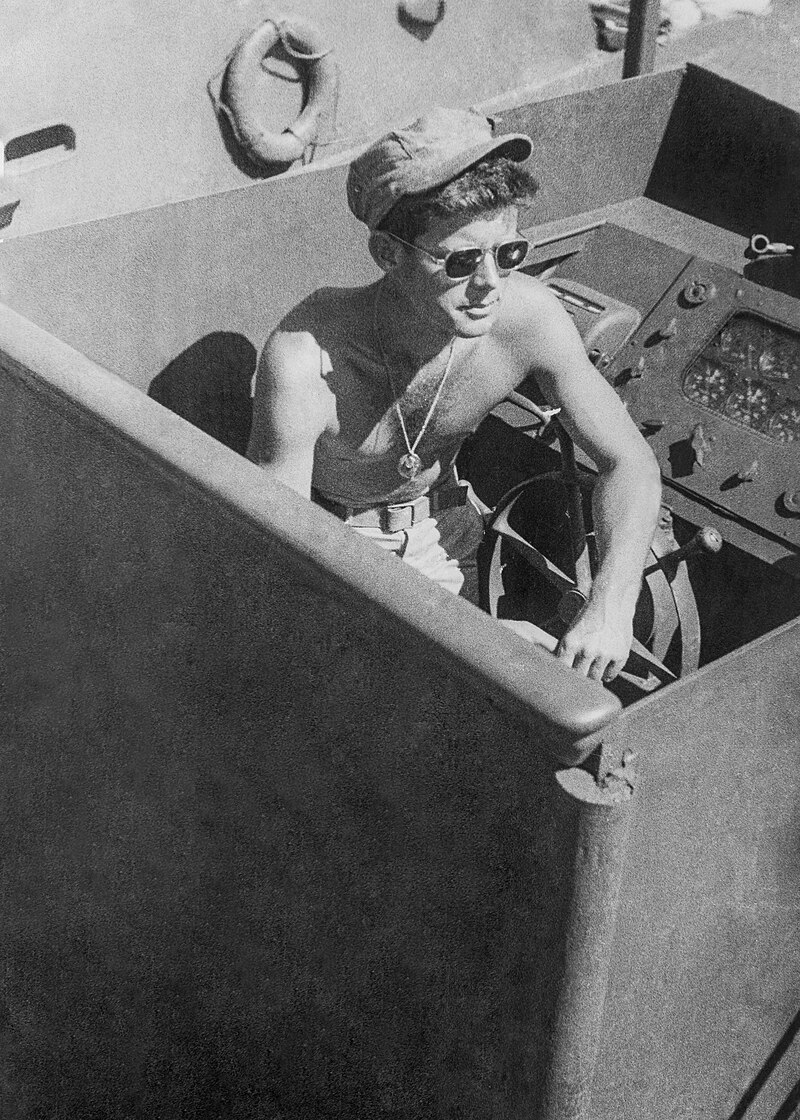

Lt. John F. Kennedy aboard PT-109

Fifteen PT-boats fired thirty-one torpedoes. One PT was lost. The only damage to the enemy resulted from Amagiri ramming PT-109. The American side of this action was hardly skillful, much less heroic. John Kennedy received the Navy-Marine Corps Medal for trying to save those of his crew that survived. The heroism that has been ascribed to him needs to be considered in the context of the loss of his boat, the death of two of his crew and injury to others. The failure of the PT-boats to stay in communication and coordinate their actions is also notable. The loss of PT-109 came after one the most active nights of PT-boat contacts with the enemy to that point.

[1] Japanese Destroyer Cuts Foe Torpedo Boat in Two, Mainichi (Eng. lang. Ed.), Sept. 11, 1943, p.1.