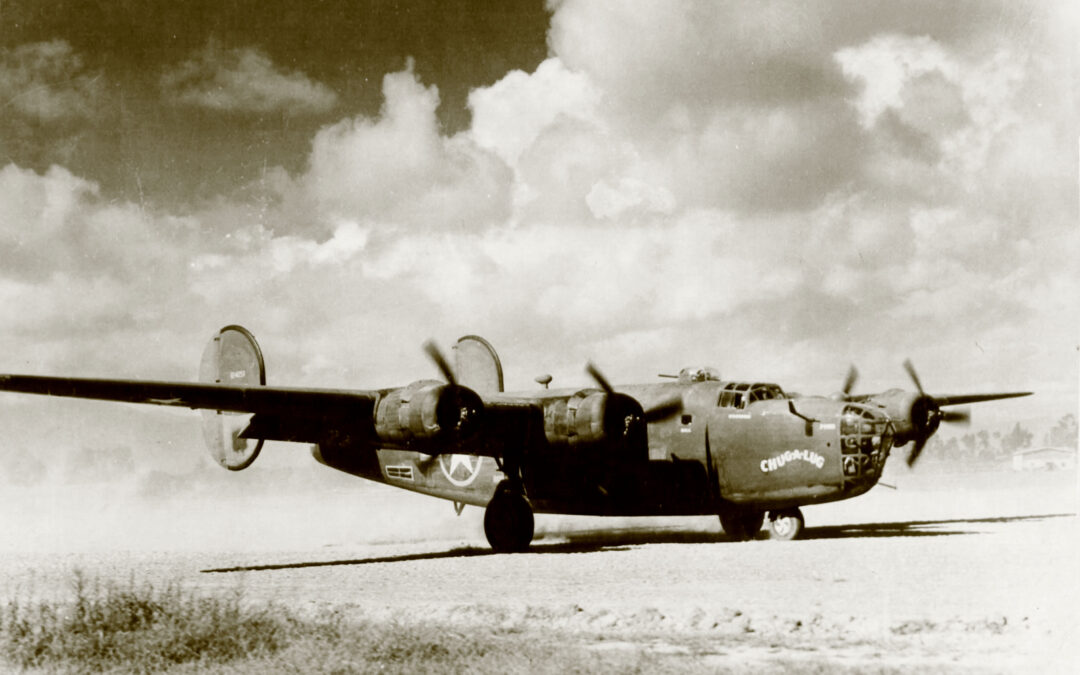

Survived the Hankow raid 8/24/43

The B-24 Liberator in China played a pivotal role in shaping the air campaigns of World War II, particularly during the summer of 1943. As one of the most versatile and far-reaching bombers in the Allied arsenal, the B-24 conducted daring missions over enemy targets, showcasing its unmatched range and defensive power. Operating under the Fourteenth Air Force, these bombers struck key Japanese strongholds, challenged advanced fighter tactics, and demonstrated their strategic importance in the Pacific Theater. This article delves into the lesser-known exploits of the B-24 in Chinese skies, highlighting its contribution to the Allied war effort and its encounters with fierce Japanese resistance.

The B-24 Liberator heavy bomber partnered with its stable mate the B-17 mounted a sustained daylight bombing campaign against German industry beginning in 1943. The heavy bombers drew German fighters away from the Eastern Front and eventually in conjunction with fighter escorts inflicted ruinous losses on them. In the Far East B-17s were the only heavy bombers available to oppose initial Japanese onslaughts. By the end of 1942 B-24s began to appear in increasing numbers in the Asia-Pacific theaters. Eventually a decision was made to rely exclusively on the B-24 there due to its longer range and to facilitate logistics simplification. Performance, bomb load, range and defensive capabilities made the B-24 a worthy substitute for the B-17 or by some calculations superior.

The story of the B-24 in the Pacific war is woven into the narrative of South Pacific Air War. Here we relate a story about the B-24 and its Japanese opponents not widely known nor well understood even when its basics are known. For much of 1942 and 1943 the American heavy bombers, the B-17 and B-24, were the bane of existence for Japanese fighter pilots. They were difficult to attack, hard to bring down and could inflict stinging losses on attackers. For their American crews their relatively modest losses and exaggerated claims of enemy fighters shot down made them seem more heroic than exploits of many fighter pilots.

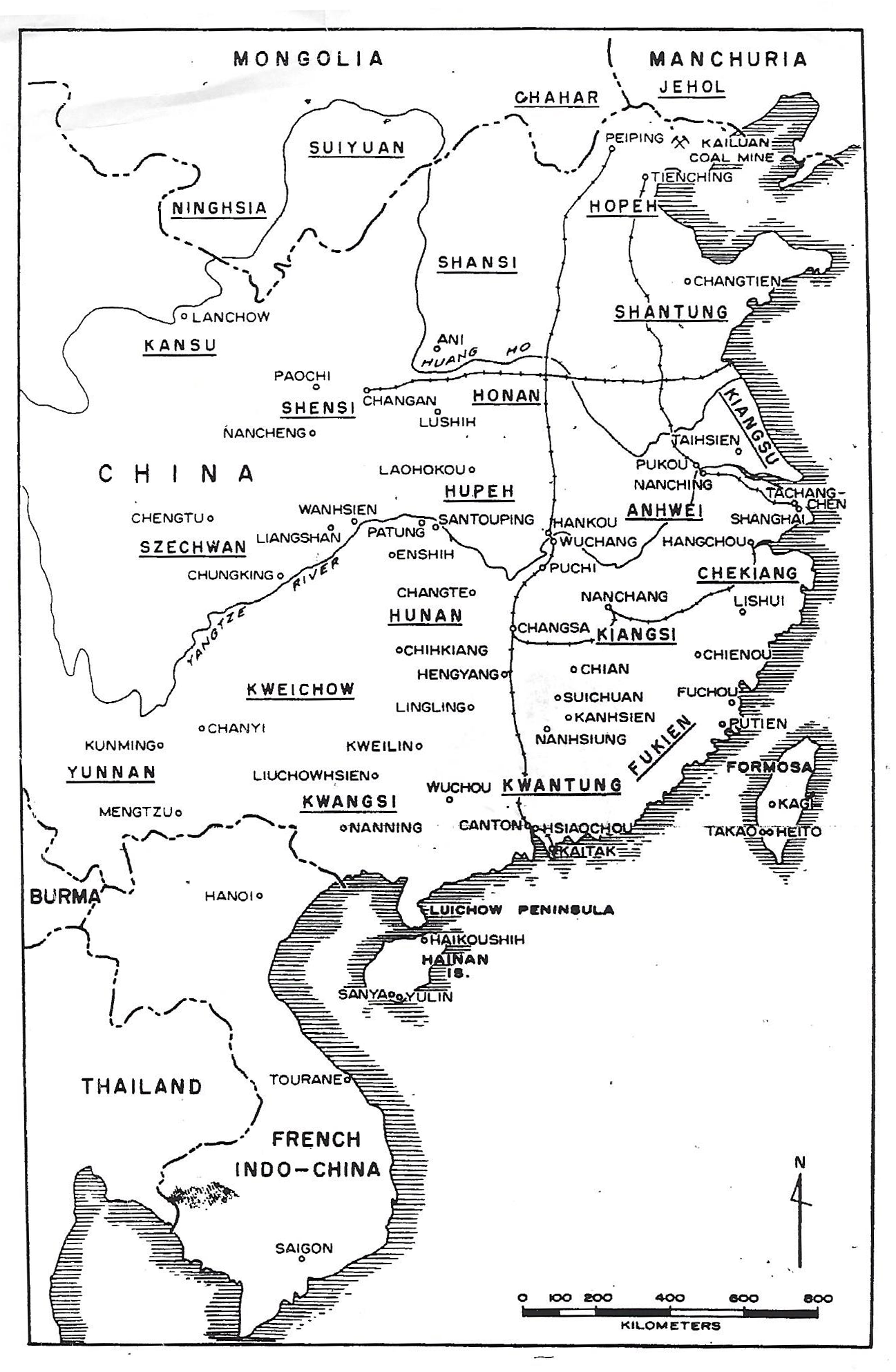

When in March 1943 Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault’s China Air Task Force (CATF) of the Tenth Air Force became the Fourteenth Air Force, it not only inherited the fighter and medium bomber units of CATF but was assigned the B-24 equipped 308th Bomb Group with over thirty B-24Ds. Liberators of the 308th first got into action on 4 May 1943. They flew 600 miles from their base at Kunming to raid targets on Hainan Island reportedly with great success. More raids followed later that month some flown from Kunming others from Chengtu. June was devoted primarily to hauling freight over the Hump supply route between India and China including gasoline for their own future operations. They were in action during July; some missions flown with fighter escorts, some without. Several of their raids were intercepted by Japanese fighters. The Japanese fighters inflicted damage on some of the attackers but the B-24s claimed large numbers of Japanese fighters destroyed or damaged. From May through July no 308th Liberator was lost to Japanese fighter attack and the group suffered only a single loss during a combat mission.

American intelligence officers wondered why the Japanese repeatedly bombed Kienow and Lishui airfields in eastern China. The airfields were seldom used by the Fourteenth Air Force but repaired by Chinese coolies each time Japanese bombers holed their runways. The Japanese concern for Kienow (Chienou) was related to its possible use as a base for bombing raids on Japan. The presence of B-24s operating in China strengthened their concern. In October 1942, B-24s of the India Air Task Force staged through Chengtu to strike the Lin-hsi coal mines, source of high grade coking coal that fueled Japanese steel mills, in far northeast China. The B-24s covered 1,100 miles to deliver their bombs. This demonstration of effective range along with the B-24’s reputation for self-defense was disturbing. Liberators operating from bases in eastern China could reach Kyushu, Shikoku and parts of Honshu on the approaches to Tokyo. In addition to the damage it could do in China the B-24 was seen as a potential threat to the Japanese home islands.

The Missions

On August 17th the B-24s of the 308th flew their first mission of the month. Some of the 22 Liberators turned back due to weather. Those reaching the target south of Haiphong encountered light AA fire and no fighter opposition. All returned to base. On the 21st fourteen B-24s of the 374th and 375th Bomb Squadrons were to join with seven B-25s and escorting P-40s for an attack on Hankow. Plans were upset by the appearance of marauding Japanese fighters over the Hengyang base of the escorting P-40s. Japanese fighters engaged in diving attacks from above the 23,000 feet altitude of the P-40s. By the time the P-40s fought off the Japanese fighters and returned to base to refuel the B-24s were headed toward Hankow unescorted. The B-24s got to the target and dropped their bombs unopposed. They were then confronted by a swarm of Japanese fighters that carried out coordinated attacks. Attacks included high frontal passes as well as attacks from various positions including beam attacks. In the first pass mission leader Maj. Bruce Beat’s B-24D Liberator (41-24243) was shot down and three Liberator pilots leading sections were wounded. The attacks kept up for nearly half an hour. A B-24J (42-40854) crashed with dead and wounded crewmen aboard. A badly shot up Liberator limped into the Lingling fighter strip. It was one of ten bombers that returned badly damaged. B-24 gunners were credited with fifty-seven destroyed, thirteen probables and two damaged. The Japanese admitted the loss of two.

A follow up raid on Hankow took place three days later. Fourteen B-24s of the 373rd and 425th squadrons, six B-25s, and fourteen P-40s and eight P-38s constituted the attacking force. Seven B-24s aborted due to weather and only seven B-24s of 425th joined the B-25s and escorting fighters. Once again there was no interception until after bombs away. The Japanese fighters estimated to number forty concentrated on the B-24s. Over forty-five minutes four Liberators went down. Three damaged bombers returned to Kweilin carrying several dead and wounded crewmen. One of these crashed returning to Kunming the following day killing all on board.

On 26 August fifteen B-24s escorted by ten P-38s and seven P-40s hit Hongkong’s Kowloon docks. Japanese fighter opposition was weak. Liberators claimed five destroyed without loss. On the 29th sixteen B-24s escorted by two dozen fighters bombed Hanoi without loss. September saw limited action due to adverse weather and commitments to the Hump supply run.

On September 14th fifteen Liberators were sent to bomb Haiphong. Five aborted due to weather. Ten bombed successfully opposed only by anti-aircraft fire. The five that turned back on the 14th were sent against the same target the following day. They were met by aggressive fighters with the lead ship shot down on the first pass. Two others fell before leaving the target area. The Japanese claimed three bombers and reported they caused negligible damage. A fourth B-24 made it almost all the way to Kunming before crashing with the loss of the entire crew. Like the 24 August mission this resulted in a squadron essentially being wrecked. A decision was made not to send B-24s on unescorted missions. Unfounded Japanese fears of B-24 attacks on the Japanese homeland could be put to rest. Not until B-29s were based at Chengtu many months later did the threat of bombing attacks on the Japanese home islands become a reality.

Little – half inch – things matter

In mid-1941 the experimental Ki 43 was officially accepted by the Japanese Army air service and received the designation Type 1 Fighter. Fighter pilots accustomed to biplane fighters and the nimble Type 97 Fighter were not initially impressed in all cases. The new fighter with underwing drop tanks had much longer range than earlier fighters. When accepted for service its armament was two 12.7mm “machine cannon.” However, the aircraft was configured to accept both the new Type 1 machine cannon (Ho 103) or the traditional 7.7mm machine gun in either right or left hand station in front of the windscreen synchronized to fire through the propeller arc. Nakajima Ki 43-I Armament, a Reassessment

Once the Pacific War began fighter pilots appreciated the power of the 12.7mm gun. However, the new gun came with problems. Cannon rounds could explode prematurely in the barrel disabling the gun and potentially damaging the engine over which the guns were placed. The 64th Flying Regiment reportedly lost three aircraft to this problem in operations during the Malaya campaign. Solutions included placing 5mm iron plates under the gun barrel blast tubes or even fashioning iron blast tubes. A compromise developed that took advantage of the aircraft’s ability to accept 12.7 or 7.7mm guns without modification. The standard armament became one of each and remained such throughout the model I’s service. Once reliability problems with the Ho 103 were worked out two 12.7mm guns became standard on the model II of the Type 1 Fighter. Even if the Ho-103 jammed the reliable 7.7mm would still fire.

With the introduction of the half inch (12.7mm) gun three types of ammunition were available. These were normal, incendiary, and armor piercing. These terms are translations from a Japanese official history. Normal probably equates to ball, incendiary needs no elucidation, however, “armor piercing” is more like explosive (hence “machine cannon”) or armor piercing-explosive. This came in two types. The MA-102 is described as a fuzeless fragmentation round. The MA-103 was a prototype fuzed fragmentation round. The fuzeless round was apparently widely used. Per Allied reports the Japanese 12.7mm explosive round would blast a hole in the thin skin of an aircraft with limited results in damaging internal components. The hole it caused, however, caused it on occasion to be confused that a Navy 20mm round fired from a Zero fighter.

What does this have to do with our story of China-based B-24 losses to Japanese fighters? The destructive effect of Japanese explosive rounds may have been enhanced by chemistry, a new explosive compound. In October 1943 the lead of a Nippon Times story was: Extraordinary Effectiveness of ‘Special Gunpowder’ Proved. The narrative credited technical officers Majors Saburo Watanabe and Ken Kitagawa with the invention and noted they were awarded medals by Prime Minister Tojo. Per the Nippon Times article:

“The extraordinary explosive power”, said Unit Commander X, “of the special gun powder was first proven when it was used against the four-engined Consolidated B-24’s that attacked the Wuhan area. On August 21, we shot down three B-24’s, which had hitherto been regarded as ‘undestroyable’. It was on August 24 that the special gunpowder displayed its extraordinary power most brilliantly. On that day an enemy formation consisting of more than twenty fighters and bombers raided this area. As I fired against enemy B-24s holes were made on the flanks of these enemy machines and I clearly saw enemy pilots turn pale. The thick glass shade which the foes had relied upon as absolutely safe was perforated and enemy aircraft fell down like balls of fire. Six B-24s were shot down that day. Our air force is invincible now that it has this special gun powder of extraordinary effectiveness.

Whether the new energetic compound was put into general use is unclear. However, there is some evidence that the new compound or possibly revised fuzing of 12.7mm rounds was having effect in other operations in China. A March 1944 Fourteenth Air Force weekly intelligence summary advised:

The Jap 50 caliber (12.7mm) explosive shell seems to have a delayed action for we have several which have penetrated through thick sections before going off. They also damaged our bullet-proof tanks to a degree where they would not seal. One of our planes landed safely after the raid on Suichwan on 12 February 1944, has been condemned due to a 12.7mm explosive round ripping the main spar between the engine and the cockpit.

How many American or Chinese aircraft failed to return because of the ‘special gunpowder’ cannot be known. It seems almost certain that the former immunity to enemy defenses of B-24s operating in China was ended by Japanese tactics of head on approaches and the increased energy in their bullets.