Aficionados of the Pacific air war will appreciate the remarkable history of the 44th and 67th Fighter Squadrons, known for their significant contributions during World War II and their notable involvement in the early stages of the Vietnam War. This article explores the fascinating South Pacific – North Viet Nam connection, highlighting key missions, brave pilots, and the evolution of aerial combat tactics from Guadalcanal to Vietnam.

67th Squadron P-400s Guadlcanal October 1942

What one might ask does any of this have to do with Viet Nam? Turns out that the 44th and 67th Tactical Fighter Squadrons, successors to the World War II outfits were also involved in early air combat in the Viet Nam war – indeed the earliest air combats. The Viet Nam War is old enough that much of it has faded from memory. Herewith, subject to the vagaries of available source material, is a brief recounting of the South Pacific – Viet Nam connection of the 67th and 44th Fighter Squadrons.

The first connection relates to the action of 3 April 1965. This was the first time the North Viet Namese Peoples Air Force (NVPAF) claimed aerial victories. April 3 became a holiday, Air Force Day. The U.S. Air Force and Navy mounted strikes against bridges in North Viet-Nam that day. The connection comes from a major element of the Air Force strike being from the 67th Tac Fighter Squadron; the leader of the large Air Force strike force was Korean War ace Lt. Col. Robinson Risner commander of the 67th. This strike against the infamous Thanh Hoa Bridge (Ham Rung or Dragon’s Jaw to the Viet Namese) involved a total of 79 aircraft including a main attack force of 31 F-105Ds plus 22 F-105Ds and F-100Ds for flak suppression. In the same general area attacking bridges a few miles from the Air Force target was a Navy attack force from carriers Coral Sea and Hancock. It consisted of 35 A-4Cs, 16 F-8Es and 4 F-4Bs. This was before the Rolling Thunder Coordinating Committee was established to deconflict and coordinate air force and navy efforts.

F-105

The gestation of the NVPAF involved a long slow process dating from the mid-1950’s. It received its first jets from the Soviet Union in 1962. By 1963 a few hundred pilots had been trained but most were flying less than a hundred transports, training planes and helicopters. With the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 and resulting U.S. retaliatory air strikes in the north creation of an air defense force was accelerated. When the U.S. sustained bombing campaign against the north (Rolling Thunder) began in March 1965 elements of the 921st Fighter Regiment (nominally thirty-six MIG-17s; gifts from the Soviet Union) were deployed operationally to Noi Bai airfield a short distance north of Hanoi. By 2 April pilots were trained, tactics practiced, and a favorable opportunity awaited. On the following day a four-plane attack flight under Lt. Pham Ngoc Lan and two-plane covering flight under Snr. Lt. Pham Giay scrambled as instructed by ground control. They flew south at low altitude to avoid U.S. airborne (EC-121) and ground radar as well as possible misidentification by their own surface to air missile batteries.

The NVPAF version of the story says the MiGs made visual contact with the Americans bombing the Dragon’s Jaw. The four fighters in the attack flight accelerated and gained altitude to make a diving attack on their opponents. A few miles from where the air force aircraft were dropping bombs and firing Bullpup missiles, they sighted pairs of aircraft attacking the Tao Bridge. The aircraft they attacked were Navy, reported as F-8s (F-8 Crusaders were typically used as escorts). First to fire was Lan’s wingman Phan Van Tuc who claimed hits. Lan quickly pressed his attack, opening fire with his 37mm and 23mm cannons from 400 meters. Hits caused the “Crusader” to explode, and it was seen to crash near the Thai Bin River. The F-8 identification was reportedly based on Lan’s gun camera imagery. Another F-8 was seen and once again Tuc took the lead and scored hits. The Crusader rolled sharply and crashed into the ground from a low height. The MiGs cleared the area quickly and were ordered to return to base. Lan had trouble with his compass, ended up out of fuel and crash-landed MiG-17 no. 2310. His comrades all returned safely. Reported ammunition expenditure was 160 37mm rounds and 526 23mm rounds.

On the U.S. side one A-4C was lost (BuNo 148557) with Lt. Cdr. R.A. Vohden of Hancock’s VA-216 becoming a seven-year POW. His loss was attributed to ground fire. The wingman saw the stricken Skyhawk trailing fluid with the tail hook dropped down. Arthur Vohden quickly ejected. A Hancock F-8 was also damaged. Unable to return to the carrier, Lt. Cdr. Spencer Thomas landed at Danang, South Viet Nam. Through the MiGs happening upon the Navy aircraft the air force strike did not encounter any MiGs but still lost a flak suppression F-100 whose pilot 1Lt. George Smith was killed. Over a hundred 750lb. bombs and thirty-two missiles (250lb. warhead) were expended on the Dragon’s Jaw. Many were hits. However, photographs showed what proved to be an over-engineered bridge suffered little damage. A repeat mission was scheduled for the following day.

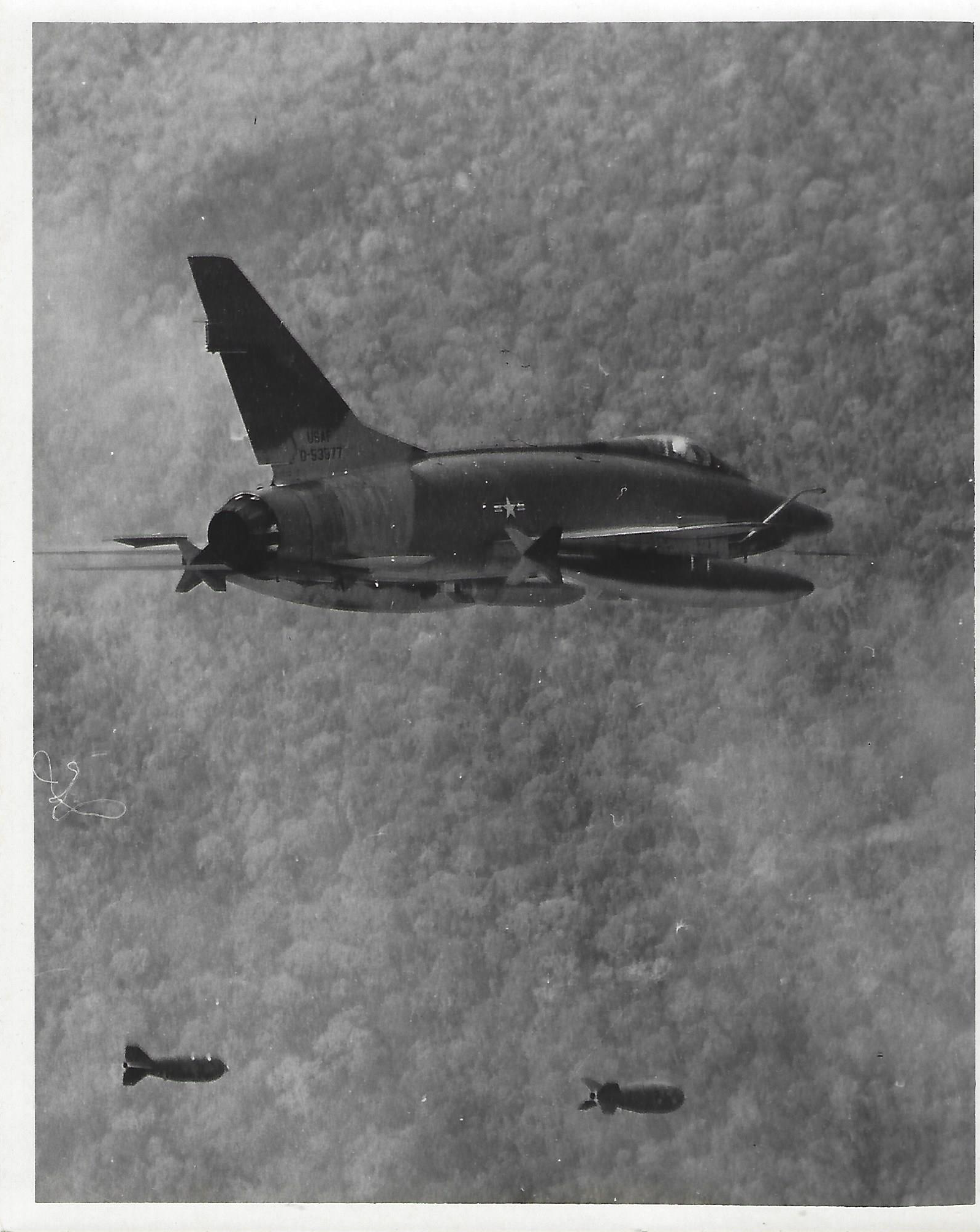

F-100D in Viet Nam

The attack the next day reduced flak suppression in lieu of more bridge busting 750lb. bombs leaving the ineffective missiles at base. Added was a flight of F-100Ds armed with AIM-9B air to air missiles as well as 20mm cannon. The 67th and Lt. Col. Risner continued to play a key role leading forty-eight F-105s in the bridge attack, eight F-100s in flak suppression/MiGCAP, two others as weather reconnaissance and air refuelers and other support aircraft. Combat resulted in USAF losses to MiGs in air combat. There were also MiG losses, at least one of which likely fell to a USAF fighter. Our first connection to the 44th Fighter Squadron also occurred.

Despite some foul ups in the approach to the target F-105 pilots pounded the bridge for the second day in a row. Among them was Capt. C.S. Harris of the 44th Tac Fighter Squadron. Flying as number 3 in his flight Smitty Harris had to eject when his “Thud” (62-4517) was disabled by ground fire. He survived but became a long-term POW.

The NVPAF scrambled two flights of eight MiG-17s, led by Pham Ngoc Lan and Tran Hanh, respectively. The covering flight leader Lt. Lan attacked the F-100 escort rather than the F-105 bombers. Tran Hanh and Pham Giay went after a flight of F-105s. Heavily laden with bombs and flying at about 375 knots the Thuds were poorly situated to defend themselves. Four F-105s from Korat AB Thailand, Zinc flight, were supposed to be the fourth attacking element. Exigencies of weather (haze) and operational (refueling) problems threw off the schedule and flights ended up orbiting the check point ten miles from the target to get sorted out. Zinc flight which was led Maj. F.E. Bennett of the 354th Tac Fighter Squadron completed an orbit and was about ready to enter its attack profile when the pilot in the number 3 position sighted two aircraft in a diving high speed approach on the flight. When they got within less than a mile and were identified as MiGs, Zinc 3 and 4 radioed warnings. “Zinc Lead, break…you have MiGs behind you. Zinc Lead break…we’re being attacked.” There was no reaction to the warning, possibly due to radio chatter. Zinc 3 then sighted two more MiGs behind the first two. Repeating the call for the formation to break, number 3 and 4 then broke left into the second pair of MiGs.

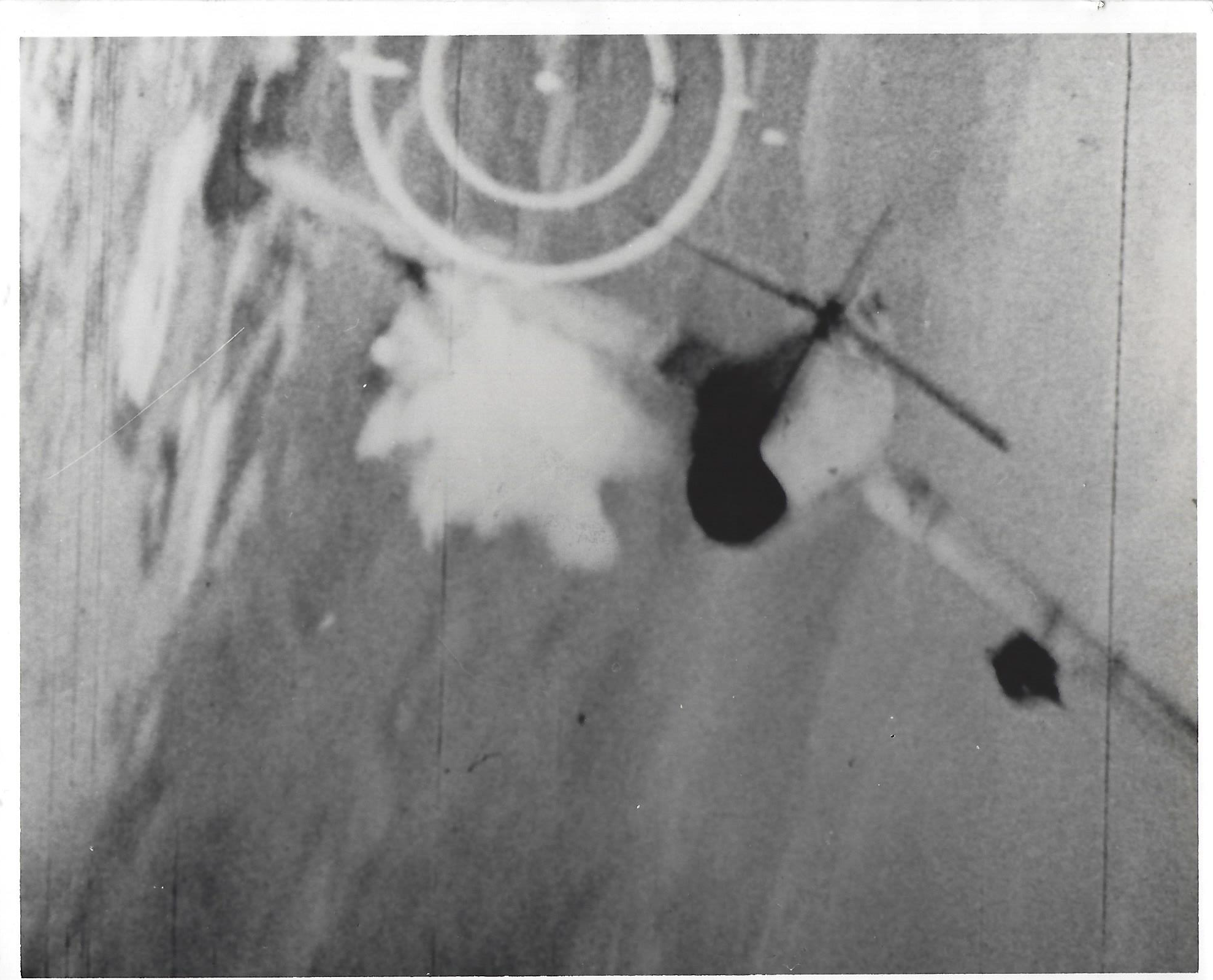

Tran Hanh apparently attacked Capt. James Magnussen who died in the crash of his F-105 (59-1764). Hanh’s second element led by Le Minh Huan hit Frank Bennett’s fighter. The Thud crashed into the sea. Bennett ejected but failed to survive the bail out. A 416th Fighter Squadron MiGCAP F-100 flight was not in position to prevent the attack but chased the MiGs as they escaped. Lt. Col. E.L. Hays and Capt. K.B. Connelly fired AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles that came close but were not seen to damage the withdrawing MiGs. Another 416th FS Super Sabre flight on RESCAP (support for rescue efforts) duty was also involved in the action. Capt. Donald L. Kilgus chased a MiG in a dive from 20,000 feet down to 7,000. Kilgus observed 20mm hits on the MiGs stabilizer and saw pieces of metal fall off the aircraft. He pulled out of his dive and in the haze did not observe his victim’s crash although he was certain that it did. Kilgus was credited with a probable victory. He painted a red star victory symbol on his Sabre (55-2894) and later during a subsequent Viet Nam tour with the 44th Fighter Squadron painted a victory star on his F-105D. There is no record Kilgus ever officially protested the probable assessment. Had it been awarded as a victory it would be the Super Sabre’s only air victory.

Gun-camera photo of MiG-17

Sources differ as to NVPAF losses. Some sources name three of the pilots from Tran Hanh’s flight as killed. Another version is that two MiGs were damaged in air combat and crash landed but their pilots survived. Some sources that claim three pilots killed suggest the cause of their demise may have been friendly fire from AA. Another version, despite the lack of U.S. claims, says they were lost in combat with F-105s. In any event apparently two or three MiGs failed to return. It seems likely Kilgus damaged a MiG sufficiently that it crashed. Possibly a Sidewinder fired by Hays or Connelly caused some damage despite failing to detonate and likewise caused a crash. Unfortunately, this remains speculation since primary source documentation from the North is not forthcoming.

For the exploits of the 44th and 67th Squadrons in the south Pacific in 1943 see chapters 4, 5, 12, 14, 17 and 20 of South Pacific Air War, Schiffer Publishing (2024).

Okay, other than this being rather interesting and a subject begging for more research, one might ask why make anything of a supposed connection between WW2 and the Viet Nam conflict? In my case there are a few reasons. In college I had an ROTC professor who had 3.5 air combat victories from the Mediterranean Theater in WW2 and wanted a fighter assignment to Viet Nam to become an ace. The only thing career management offered was a C-47 gunship. To cap it there was a report of pilots water skiing on the river near Saigon being fired on by snipers. “Not my kind of war” he said. Luckily, I got a flight in a T-33 (two-seat version of the F-80) with him. Also, in college I got to meet Harrison Thyng who was running for U.S. Senate in New Hampshire. He was CO of the 309th Fighter Squadron in WW2 and an ace in both WW2 and Korea. The 67th FS also has a Korean connection. It transferred from the Philippines to Korea but gave up its F-80s and flew F-51Ds for most of the war.

F-4Es at Homestead AFB

After law school my first active-duty assignment in the Air Force (1970) was at Homestead Air Force Base. I had official business with the base civil engineer, Walt Williams. I also interviewed him about his duty as a fighter pilot in China in WW2. Our Wing CO Wiltz P. “Pancho” Segura was a WW2 ace from the China theater. While at Homestead I was inducted as an honorary member of the 309th Tac Fighter Squadron. The Squadron CO Chic Heatherington took a break in service after duty in WW2 but was back for Viet Nam. He elucidated for me the similarity between P-38 versus Zero combat and F-4 Phantom versus MiG-21 combat. Finally, I had occasion to meet on his last active-duty assignment Col. Abner Aust, self-styled “last ace of WW2.” He also flew combat in Viet Nam. Let me merely say his life story is “remarkable”. I shared some of it with Justin Taylan who a few years ago trekked to Polk County, Florida to interview Col. Aust before he passed away. Check out Pacificwrecks.com website for details absent the sordid parts which are most interesting.