This article was previously posted on J-Aircraft.com forum in 2003. An addition has been made at the end to include correspondence and photos from Harumi Sakaguchi, who visited Kitava and interviewed locals and witnesses. Click here to scroll to the end of the article and view the addition.

SOUTH PACIFIC, September 11th, 1942. September 1942, near the end of winter in the southern hemisphere; war had raged in the Pacific for nine months. The hot point of the Pacific war was concentrated in a rough triangle of conflict running from Rabaul on New Britain Island to eastern New Guinea (Port Moresby, Buna, Milne Bay) across the Solomon Sea to Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands. Air patrols and air combat were nearly constant throughout the region. Crucial land battles raged on New Guinea and on Guadalcanal. Strong naval forces had clashed in the region and continued to concentrate for renewed combat.

The "Tri-angle of conflict" (US Army)

In the skies over Guadalcanal. Something was wrong! The control stick was pulled back, the throttle set for combat power, but the airplane wasn’t climbing. It was losing altitude. The propeller was turning too slowly. All thoughts of another attack on the American plane vanished. Shigenori Murakami knew he was in trouble and must act. Slewing drunkenly in its awkward nose-high attitude the Zero fighter sank toward Guadalcanal. Murakami struggled to control the balking fighter. The fuel selector valve was right below the throttle quadrant by his left hand. There was no need to hold the throttle with its gun trigger at this point. Murakami turned the valve to select the main fuel tank. Power surged through the fighter as additional gasoline reached the Sakae engine. The gray fighter with the rising sun insignia and the notation U-107 on the tail was soon flying normally. Murakami quickly searched the sky around him. He was alone.

Invariable target-Henderson Field (USMC)

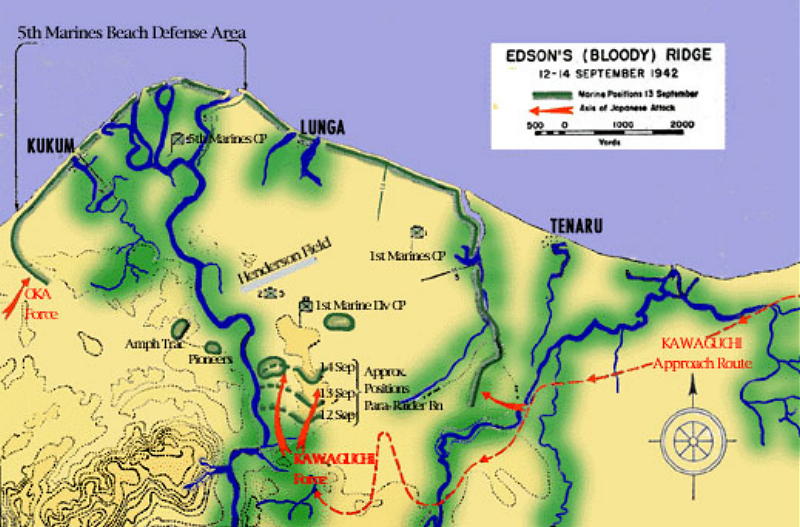

Japanese army forces were concentrating for a major offensive on Guadalcanal a key part of which was to be a push from south of the island’s airfields into the airfield and supply areas of the U.S. defensive perimeter. On September 11th Japanese naval air units flew one of their almost daily (weather permitting) attack missions against Guadalcanal to support the coming ground offensive. Weather allowed the Japanese to launch only 14 attack missions during the 23-day period from August 21st to September 12th and four of these were aborted due to weather. During the mission on the 11th two Japanese aircraft failed to return. One was a Type 1 land attack bomber of the Kisarazu Kokutai (Air Group) captained by Petty Officer 1/C Tadayuki Shimada. The second aircraft was a Type Zero carrier fighter (“Zero”) of the 6th Air Group flown by PO 2/C Shigenori Murakami.

Pilots of VMF-224 - September 1942 (R.E. Galer)

A respected book on military history informs us that Zero pilot Petty Officer Murakami was killed that day. Furthermore, since only one Japanese fighter was lost and only one American fighter pilot claimed a certain victory over a fighter that day it seems logical to conclude, as some historians do, that Major Robert E. Galer of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF)-224 shot down the Zero that was lost.

This article shows Galer did not shoot down Murakami nor did Murakami die that day. Moreover, Murakami’s ultimate demise involved events ranging across the entire breadth of the “triangle of conflict.” Herewith is presented (with due apologies to Paul Harvey) “the rest of the story” of Shigenori Murakami. Only by exploring events from another corner of the “triangle” far removed from Guadalcanal could evidence of Murakami’s fate be found and the events surrounding it be put in perspective.

THAT DAY AND BEFORE. On the afternoon of September 11th the Zero fighters of the 6th Air Group returned to Rabaul from the long flight to Guadalcanal. Lt. Mitsugu Kofukuda counted his returning fighters. One was missing. Returning pilots reported the results of the mission. Petty Officer Murakami was last seen attacking a B-17.

11th Bomb Group B-17 over the Solomons (NARA)

Murakami was the 6th Air Group’s first combat loss at Rabaul. The 6th had arrived less than two weeks earlier. Only part of the unit was at Rabaul. The bulk of the unit was en route from Japan traveling via Truk on the aircraft carrier Zuiho. The initial detachment of eighteen fighters had flown to Rabaul from Japan via Iwo Jima, Saipan, and Truk. Only experienced pilots had been included in the advanced echelon. Murakami was deemed sufficiently experienced to be included as part of the detachment. He had completed his fighter training at Oita in November 1941. Final operational training had been rushed so that Murakami and his classmates could be available for combat assignments prior to the start of the Pacific war. In April 1942 he was assigned to the newly organized 6th Air Group. The unit was to be part of the land-based air garrison for Midway Island after its planned capture. The group lost all its aircraft and several pilots during the June operation. In August, after the invasion of Guadalcanal by U.S. Marines, the re-constituted group was ordered to the South Pacific. Most of the advanced echelon arrived at Rabaul on August 30th and flew several missions prior to September 11th. They provided air defense at Rabaul; operated from Buka in the Solomons and Lae in New Guinea: and, had flown offensive missions to Buna, Milne Bay and Port Moresby in New Guinea. September 11th was their first mission to Guadalcanal.

Murakami was one of the 6th Ku advanced detachment members (Hata/Izawa)

The single largest Japanese air operation on September 11th was the bombing attack on Guadalcanal. Twenty-six Type 1 land attack bombers from Misawa and Kisarazu Air Groups escorted by fifteen Zero fighters (six from Murakami’s 6th Group) made up this mission. The Allied codenames BETTY and ZEKE had been adopted for these aircraft but the terminology was not in general use at this time. Other air operations saw flying boats from Shortland Island making patrol flights out to 600 miles covering a wedge between 75 and 120 degrees from that base. Land attack bombers from Rabaul also flew long-range patrols covering the sector between 98 and 138 degrees. A single Type 98 reconnaissance plane reconnoitered San Cristobal Island southeast of Guadalcanal. Two flights (shotai) each of three Zeros were sent to cover destroyers Isokaze and Yayoi

engaged in a rescue (troop extraction) mission to Goodenough Island. Both flights were turned back by weather. Some of the patrol missions also turned back early due to weather. Clouds and rainstorms blanketed large segments of the operational area.

Despite the extensive nature of Japanese navy air operations on the 11th they failed to meet all requirements. No missions were flown to support army ground troops engaged in combat in the Owen Stanley Mountains of New Guinea. The previous day the navy had received a delayed army message advising that on September 7th three Allied air attacks had inflicted approximately 100 casualties among their troops. The message requested fighter support. The navy could not comply with the request.

EVENTS OVER GUADALCANAL. The attack on Guadalcanal that day was hardly a surprise. The Japanese had to fly 565 nautical miles from Rabaul and also try to avoid thunderstorms that, while unpredictable, tended to develop in the afternoon. This dictated an early morning take-off and a midday arrival over Guadalcanal. This, plus advanced warning from coast watchers and radar, usually allowed relatively slow climbing Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighters to climb to an advantageous high-altitude position and attack the Japanese in diving attacks from above.

Wildcat on henderson Field (NARA)

So predictable were the Japanese attacks that three war correspondents chose September 11th to observe them from a choice spot overlooking Henderson Field, the invariable target. Driving by jeep to the bottom of a ridge south of the airfield they parked near the headquarters of the 1st Marine Division. Tillman Durdin, Robert Miller, and Richard Tregaskis hiked up the hill until they cleared the trees and reached an open, grassy area. There they found a partially dug bunker and decided it was the perfect spot to observe the expected air raid. In a few days they would call the ridge they were on “Edson’s Ridge” (after the Marine commander who held it). To the Marines it would become “Bloody Ridge” and indeed it was the scene of one of the many bloody slaughters on Guadalcanal.

Bloody Ridge (USMC)

The correspondents got more than they bargained for. The Japanese air raid appeared well after the noon hour somewhat later than usual. However, the rushing sound of falling bombs was louder and shriller than the journalists had heard before. The correspondents and nearby Marines dove into the unfinished bunker as the first bombs exploded nearby and “walked” down the ridge past the 1st Marine Division headquarters onto the airfield.

Japanese ground attack-September 1942 (USMC)

Tillman Durdin dug a hot piece of shrapnel out of the sole of his shoe as cries of “corpsman” were heard in the area of the Marine Division headquarters. Farther away bombs blasted an Army P-400 Airacobra fighter and a Marine Wildcat. Major Dale Brannon and other pilots of the Army Air Force 67th Fighter Squadron were badly shaken and temporarily buried in the debris of a bomb shelter hit by a Japanese bomb. Eleven Marines were killed and about a score were wounded. Among the wounded was Lt. Col. Harold E. Rosencrans, commanding 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. He was unavailable to command his battalion during the coming Japanese offensive.

Wildcat damaged by bombing (USMC)

Soon after the bombing the correspondents heard the rattle of machine-gun fire high in the cloudy sky above. Later they received the report that Marines had destroyed six bombers and a fighter in exchange for several Wildcats shot up but with only one fighter lost and no pilot casualties.

After the Japanese bombers launched their attack, five fighters of VMF-223 slanted down in their counter-attack. They had received ample warning of the attack and had the advantage of higher altitude. Also in the sky over Guadalcanal were seven other Wildcats of VMF-224. They had flown an earlier patrol mission and were still refueling when the alert came. They took off about a half hour after VMF-223 and were still climbing when the Japanese bombers rained destruction on American positions. One of the wounded Marines was a VMF-224 ground crewman, Corporal George H. Kittredge, Jr.

The Marine fighters and the Japanese attack force of twenty-six land attack bombers and fifteen Zeros have already been mentioned. Two other airplanes were also headed toward what was becoming a crowded block of sky in the vast south Pacific. The return course from San Cristobal took the Japanese Type 98 reconnaissance plane over Guadalcanal. Headed toward Guadalcanal after a photographic mission to Gizo Island was a B-17 of the 11th Bomb Group.

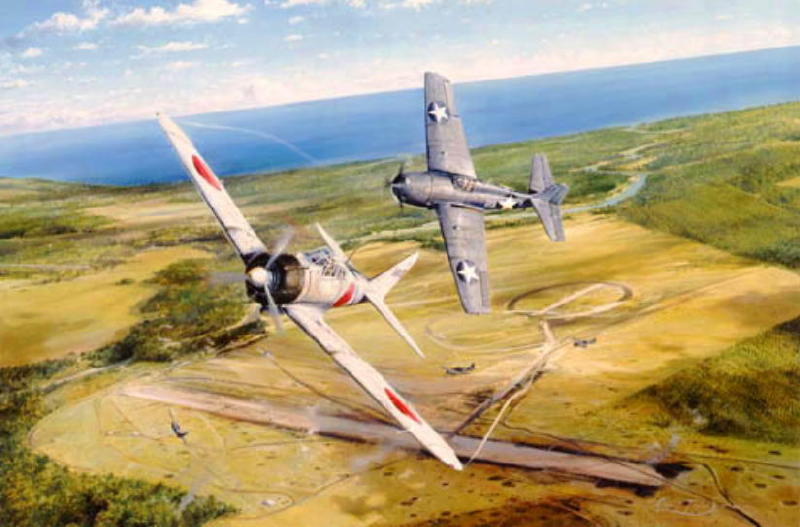

American and Japanese records available to the author paint a less than perfectly clear picture but provide an outline of the action. Murakami as part of the 6th Air Group contingent may have been flying as indirect escort (“air annihilation unit”). Murakami, at least, was not in position to see VMF-223’s initial attack on the bombers nor does he record having seen any bombers fall much less the five claimed by VMF-223. He did see Grummans and other Zeros fighting. The Marines apparently got in only one pass at the bombers and then had to elude Zeros. One of the VMF-223 pilots, Lieutenant Willis S. Lee III, claimed a Zero probably destroyed. Murakami may also have witnessed Major Robert Galer, the only member of VMF-224 to engage the bombers, in combat.

Zero and Wildcat above Guadalcanal (R. Taylor via Military Gallery)

Galer got to 26,000 feet before attacking the bombers that were then headed back toward Rabaul. He dove to attack and reported smoking one bomber that fell out of formation. Continuing his dive he sighted two “Nagoya Zeros” and commenced a high overhead run at about 6,000 feet hitting one and then the second from which he thought the pilot probably bailed out. According to Galer after “pulling out of the dive, I took after a Zero. But I didn’t pull around fast enough, and his guns knocked out my engine, setting it on fire. We were at about 5,000 feet…so I…dove headlong for some clouds…Coming through the clouds I didn’t see any more Japs…I sat down in the drink some 200 or 300 yards from shore and swam in, unhurt.”

Right: Major Robert E. Galer (USMC)

Whatever the 6th Air Group’s original assignment it moved into close escort position after the bombing attack and subsequent combat. The two shotais flew both above and behind the bombers on the return flight. It was at this point that Murakami sighted the B-17 coming out of the clouds below the Japanese formation.

Capt. Robert B. Sullivan piloting B-17E, no. 41-9227, of the 431st Bomb Squadron, was flying at 12,000 feet only a few miles from Henderson Field when he saw above him what appeared to be twenty-seven or more Mitsubishi Type 97 heavy bombers with an escort of as many as fifteen Zeros. Sullivan dropped the nose of his aircraft, advanced the throttles, headed away from Henderson Field and looked for a cloudbank as he jettisoned his unprotected bomb-bay fuel tank. The Japanese bombers proceeded on course as Japanese fighters peeled off to chase the B-17. In the ensuing combat Sullivan sighted one or more Japanese aircraft with fixed landing gear in addition to the Zeros. He identified the Japanese reconnaissance plane as a possible Type 97 fighter but more probably an Aichi dive-bomber.

Sullivan’s combat report records the Japanese attacks in some detail. They were unique in being the first coordinated attacks (generally in threes) experienced by his group. The pilots carrying out the attacks were deemed less experienced than those in previous encounters. The attacks usually came from above out of the left rear quarter. Only one pass is recorded as coming from above and the right frontal quarter. This was Shigenori Murakami’s initial pass. Murakami dove from a much greater altitude for a frontal attack but his approach didn’t go well and the attack was ineffective. Sullivan reported the steep approach shielded the attacking fighter from the B-17’s nose guns. Murakami made other passes. During one of these “two tongues of flame leapt from the center of the (B-17’s) left wing. The enemy, however, continued his flight apparently undismayed.”

Whatever Murakami saw it was not cannon shells exploding on the wing. Despite Murakami’s persistent attacks and those of his comrades, after ten minutes of furious combat during which the B-17 expended all its ammunition and claimed four Zeros destroyed, the bomber escaped into cloud cover. The only damage it suffered was a parted radio antenna. No. 41-9227, “Yankee Doodle, Jr.” was finally lost in a crash at Espiritu Santo on December 31st, 1942, reputedly during a booze run.

In addition to four victories the bomber’s crew reported another possible victory. This was a “fighter, which was hit, and when last seen was turning aimlessly and losing altitude rapidly, though apparently trying to climb.” This could well have been Murakami and along with Murakami’s own recollection of this action provides the basis for the description in the boxed paragraph.

Murakami would later reproach himself for mistakes made during this action. The first was to break formation. Then he failed to break off combat as soon as his plane took hits. He failed to regain contact with his shotaicho (flight leader) and had to return alone.

After attacking despite his aircraft not performing well (“losing my head”, according to his self-admission), Murakami correctly assessed the situation and switched to the main fuel tank. The fuel gauge showed (he later suspected it was incorrect) that he had at least 325 liters of fuel remaining. Murakami determined this was enough and he took up a course of 296 degrees for Rabaul.

EXTENDED JOURNEY. Two hours flying brought Murakami to Bouganville Island. Murakami probably knew the Japanese had recently occupied and were developing an airfield at Buin in southern Bouganville. He undoubtedly knew that the Japanese sometimes used the pre-war airfield on Buka just north of Bouganville as an operating base. On a clear day this airfield might have provided refuge. Murakami was, however, surrounded by clouds. Cumulus clouds lay ahead and behind him and cumulonimbus clouds obscured most of Bouganville from view. He was more than half way to Rabaul and pressed ahead.

Near the northern tip of Bouganville Murakami was only 190 miles from Rabaul. He took up a course of 285 degrees. He planned to cross the open water between Bouganville and New Britain and then pick up a landmark (Cape Lambert) on New Britain’s north coast for a final approach to Rabaul.

Thirty-five minutes after changing course Murakami entered clouds and began flying on instruments. He flew fifteen minutes on instruments in a box pattern to try to find a break in the clouds. From 6,000 meters he eventually went as low as 300 meters but could not sight land or the sea surface. Murakami then decided to turn back for Bouganville and the last clear sky he had seen.

He turned on to a course of 100 degrees. After half an hour he broke out of the clouds but was still in rain with visibility practically nil though he could finally discern the sea surface below. Murakami knew he had little fuel left. Fifteen minutes flying confirmed his fear. The Sakae engine began to sputter. He nosed down, dropped his external tank, and landed in the sea. Zero U-107, Murakami’s “beloved plane”, floated for about three minutes before sinking. It was about 1445 (Tokyo time). Before the plane sank, he quickly organized a few available items as a makeshift survival kit before splashing into the rain swept sea and watching his aircraft sink. With his plane gone and alone in the sea Murakami briefly considered killing himself with the pistol he carried. A mental vision of his country’s flag and the need to do his duty changed his mind.

Murakami’s prospects for survival were slim indeed. Japanese navy fighter pilots at this time were equipped with a kapok life vest but did not carry a rubber raft or any other type flotation device. Bobbing up and down with the waves Murakami caught sight of the external fuel tank he had jettisoned just before landing. Murakami swam to the tank and snagged it. He had his flotation gear! It was then he must have noted that “the continuation member of (his) fuel pipe” (the Zero fighter had a long slanting tube that projected from the external tank to connect with the internal fuel system) was damaged. This was no doubt the cause of his fighter’s problems over Guadalcanal.

Zero drop tanks showing "continuation member" (AWM)

After thinking briefly of family and friends, Murakami began to gather his wits and consider his circumstances. He had brought his knapsack with him and from that he retrieved rations and ate part of his water-soaked lunch. He had tucked his watch and an aeronautical chart in his flight helmet. His comrades from the 6th Air Group had no idea where he was. His survival, questionable as that might seem, was in his own hands and those of the elements.

Clinging to the jettison tank Murakami began to swim in what he thought was a westerly direction. Presumably this would bring him to New Britain. It is not clear where Murakami was at this point but it seems likely he was closer to Bouganville than New Britain. It continued to rain and it seems doubtful Murakami had a very clear idea of his direction. His swimming, which must have been intermittent, was unlikely to overcome the drift of ocean currents. The drift at that time of year was likely to the southwest and the usually prevailing winds were to the northwest. If Murakami was actually between New Britain and Bouganville and if expected seasonal conditions prevailed, he might indeed drift west to New Britain.

Murakami swam throughout the late afternoon and the night. By morning he felt like he had come a long way but he was hungry and felt faint. He clutched the fuel tank. As he did he couldn’t help but drink seawater that splashed into his face.

A full day went by followed by a second and third. No island, not even a reef, came into view. His only companions were a school of flying fish. He continued trying to swim while holding the tank but he was exhausted and his efforts must have been feeble.

On the morning of what Murakami thought to be the fourth day it was clear and he watched the sun dawn in the east. He felt he had done his duty and now there was nothing left but to die. For the second time since crashing he put his pistol to his head. The trigger wouldn’t move. Days of emersion in seawater had rusted the mechanism.

Murakami vacillated. Did he desire life or death? Eventually he resolved to try to live as long as possible. Rain had given way to sun and the sun’s glare soon became painful. He took in more seawater. His body seemed to be trembling. Wracked by self-doubt and self-condemnation, Murakami was now being blown along by a strong wind under clear skies. For the first time an airplane – an enemy airplane – passed overhead. Murakami also realized the drift had been taking him in a southerly direction.

Attempting to die, resolving to live, recounting his sins, seeing an enemy plane, and realizing he had been traveling south rather than west had made this an eventful day for Shigenori Murakami. He concluded any attempt to swim was useless. Wind and wave would work their will. The sun was low on the horizon on this eventful day when Murakami saw – an island!

Once again the weary Murakami tried to swim. After sunset the black mass of the island remained visible in the darkness. The night later became very dark but somehow Murakami kept the island in view. Utterly exhausted he reached the island and staggered on to the sand and collapsed. He later estimated it was about 0400 hours on September 15th but he may have been mistaken by an entire day.

After sleeping like a “stone” for many hours, Murakami awoke in daylight. He soon had a visitor. A pig ran to his side, grunting, and began to poke its snout at his knapsack. The remnants of a now rotten lunch may have been the attraction.

The island was small but it was inhabited. Black haired, black skinned islanders soon found Murakami. Unable to communicate verbally, Murakami’s gestures of putting hand to mouth soon resulted in the natives bringing coconuts and uncooked yams. Though Murakami considered them delicious, he managed through gestures to convince the natives to roast some of the yams.

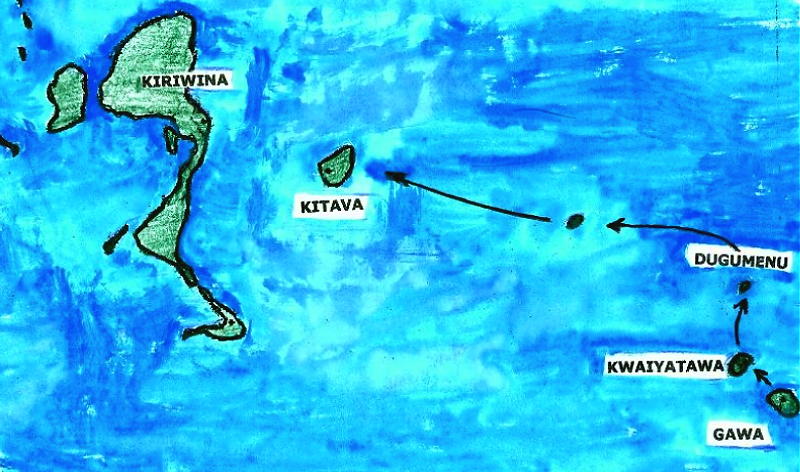

Murakami made himself known as Japanese and thought the natives were “delighted” to learn this. With additional attempts to communicate and the help of his map Murakami discovered he was on Gawa Island. He was dismayed to see how far south he had come.

Murakami’s first instinct was to return to his base as quickly as possible. He soon learned he was in no shape to do so. That night he slept in a native hut made of coconut logs with a roof of coconut leaves. He was weak and exhausted. The night air seemed chill and sleep was difficult. He suffered stomach pains and realized he was in a poor state of health.

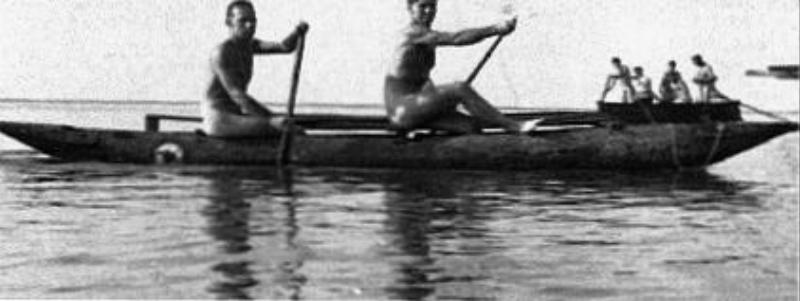

On September 17th Murakami left Gawa in a native “ship.” He does not describe it in detail but it is likely it was an outrigger canoe with several paddlers. In about three hours they reached Kwaiyawata Island. This island was also inhabited by a small band of natives and they came out to greet the arrival of the canoe. Murakami had suffered stabbing pains in his stomach during the voyage. Upon landing he felt miserable. The natives enjoyed a meal but Murakami could not join them. At night he couldn’t sleep. His spirits sank.

Australians in a small Trobriands outrigger (AWM)

On the 18th the ailing Murakami and the natives were back in the canoe. After some hours they reached Dugumeru Island. Murakami had been in pain during the voyage and his depression continued. Upon reaching the island the natives caught fish. Murakami was served fried fish and yams. He found himself growing accustomed to native food. Able to eat, his spirits improved. The natives made hot compresses for his stomach. Whether effective or not Murakami must have appreciated the gesture.

The natives carried out repairs on the canoe. Murakami helped by stripping branches. He got additional exercise by going for a walk along the shore. He soon found himself short of breath. He built a crude hut for himself and got some rest. After three days on the island he felt that his health was improving.

On September 20th the canoe (the “Waga”) set off again. After paddling some hours out of sight of land in choppy seas Murakami became concerned. Native navigation proved reliable, however, and soon Iwa Island came into view.

On clear days Kitava Island could be seen from Iwa. Kitava was the next stop on Murakami’s journey. Beyond Kitava was the larger island of Kiriwina. At Iwa Murakami’s continued attempts to communicate with the natives led him to the impression that they believed “English” soldiers might be on Kitava and possibly on Kiriwina. It is unclear whether Murakami gave any credence to these reports. One thing is known. Murakami began to sight Allied bombers flying past Iwa on a daily basis.

As a non-commissioned officer pilot Murakami was probably not particularly well informed on the details of Japanese troop movements. However, having flown missions to both the Buna area and Milne Bay, he was aware Japanese troops were engaged in combat operations along New Guinea’s northeast coast. On the day of Murakami’s final mission Japanese fighters had been scheduled to fly cover for ships evacuating Japanese sailors from Goodenough Island. He may well have been aware troops of a naval landing force (sometimes called Japanese “Marines”) were present on the islands off of New Guinea.

TSUKIOKA FORCE. On the day Petty Officer Murakami stumbled ashore at Gawa Island he became one of more than four hundred Japanese naval personnel present on the islands north of New Guinea’s northeast coast. The others were in two main groups on Goodenough and Normanby Islands, respectively.

Like Murakami these sailors were not there by design. Their presence was a result of the Japanese navy’s ill-advised and ill-fated attempt to capture Milne Bay on the eastern end of New Guinea. Planned to support the Japanese army advance over the Owen Stanley Mountains to Port Moresby, the Milne Bay operation actually diverted critically needed Japanese resources from the decisive sectors on New Guinea and at Guadalcanal where they might have had a telling impact.

The Japanese plan called for landing two waves of well-equipped naval landing troops from Rabaul inside Milne Bay under strong naval escort. A smaller third element proceeding from Buna via motorized landing craft (MLC) was to land at Taupota on the New Guinea coast north of Milne Bay, proceed over the mountains to the south and outflank the Australian defenders. Had things gone according to plan the total Japanese force would still have been outnumbered by more then two to one by the defenders on the ground. Australian aircraft were prepared to support their ground troops and they could also interfere with the superior Japanese sea power. Things did not go according to plan. The third element never got to Taupota.

Seven MLCs from Buna proceeding to Taupota stopped at Goodenough Island on August 25th, 1942. There the troops rested, ate lunch, and prepared combat rations. There were 353 troops comprised of a reinforced company from the Tsukioka Butai (Force), Sasebo No. 5 Special Naval Landing Force (Commander Torashige Tsukioka, commanding) supplemented by a few engineers of the 14th and 15th Pioneer Units (Setsueitai).

This force had been tracked since the previous day by Australian shore and air reconnaissance. It had been spared earlier air attack because the RAAF was busy opposing the main invasion fleet approaching Milne Bay and also because of a Japanese air attack on Milne Bay. Early on the afternoon of August 25th luck ran out.

Ten Kittyhawks of 75 Squadron (RAAF) were sent out to attack. Nine Kittyhawks completed the mission. Two flights under F/O John W.W. Piper and F/O Geoffrey C. Atherton took turns making strafing runs and flying top cover. Each flight carried out six strafing runs. All seven MLCs were destroyed along with much of the rations, munitions and equipment aboard. The Japanese were left with no means of outside communications. Eight Japanese sailors were killed and dozens wounded, some seriously.

The Japanese troops were stranded on Goodenough Island but they were not alone. The island had a relatively substantial native population as well as a few missionaries and ANGAU (Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit) personnel. Some of the natives were employed as “police boys” and “boss boys” under ANGAU authority.

On August 26th and 27th the Japanese marched south along the coast to points between Kilia Mission and Galaiwai Bay in extreme southeast Goodenough and set up precautionary defensive positions. The next day a patrol was sent to find a reported coast watcher (“white man with a radio”) but was unsuccessful. On September 1st the first of two “do or die” units (three men in a native canoe) was sent off to make the 180-mile trip to Buna and request rescue.

The Japanese were subjected to occasional air attacks but attacking planes seemed to have trouble pinpointing Japanese positions. September 8th was a day of repeated air raids and several men were injured. Unknown to the Japanese on Goodenough was the fact that the Japanese invasion of Milne Bay had failed and the surviving troops there had been withdrawn. A number of stragglers were left behind and some of these made for Taupota perhaps hoping to meet up with Tsukioka Force! In any event, the band of Japanese on Goodenough was now the largest un-subdued Japanese force close to Milne Bay.

On the same day Tsukioka Force received unusually heavy air attacks the Japanese were also active in the skies of eastern New Guinea. Nine Zeros and nine land attack bombers attacked the airfield at Milne Bay. The same fighters also reconnoitered the Taupota area for the Tsukioka Force but, of course, failed to find them there. Nine other Zeros tried to supply cover for ships involved in evacuating troops from Milne Bay but failed to sight them. A Type 98 land reconnaissance plane searched Goodenough, Fergusson, and Normanby Islands looking for suspected Allied airfields but sighted neither airfields nor the Tsukioka Force. Allied observers on the ground saw the aircraft flying low with the crewman in the rear seat using binoculars.

The Tsukioka Force had no rice and little other food (a westerner can hardly fathom the significance to a Japanese of that era of rice in his diet). They were able to collect potatoes from local gardens (looted according to some Allied reports, bartered per the Japanese) and produce salt from seawater to supplement their meager rations. A considerable number of men fell sick to malaria.

Scouts were sent out to find native canoes to mount a second mission to Buna. They eventually found canoes and damaged vessels described as a sailing cutter and a yacht. Meanwhile the first “do or die” trio (Seamen Tomei, Maezoko, and Tokeiji) arrived at Buna on September 9th having subsisted on little more than coconut milk for eight days.

The results of the “suicide squad’s” effort became apparent at about 0710 hours on the 10th. A land reconnaissance plane appeared and dropped a message cylinder. The message contained these words: “…on the 11th, the destroyers Isokaze and Yayoi will be sent to rescue you.” The message contained additional details. The airplane also dropped fifty packs of cigarettes. Smiles adorned the face of every man.

As darkness approached on the 11th the troops assembled on the beach. There they stayed until about 0100 hours the next morning. The destroyers did not come. The disappointment the troops felt can only be imagined.

At 1215 hours on the 12th a new Type 2 large flying boat swooped low overhead and dropped a message cylinder and twenty-two supply packs some on parachutes and some in special airdrop containers. The message announced that owing to circumstances the destroyer mission was postponed. It also said the destroyers would return when an opportunity presented itself and “Stick it out!” The packages contained “food high in calorific value”; cooked beef and vegetables; dried fish; and, dried bread.

No sooner had the supply drop been accomplished than two Kittyhawks appeared. Before they could attack, the big four-engine flying boat evaded into cloud cover. Disappointed at failing to catch such juicy prey the Aussie pilots noted the “T-shaped” ground-to-air cooperation panels in the treetops and contented themselves with strafing these and the nearby area. After this encounter Allied aircraft patrolled the area daily and carried out frequent attacks on suspected targets. The first casualty from these attacks came the next day when a seaman was killed by machine gun fire.

YAYOI DISASTER. On September 11th, the day of Petty Officer Murakami’s last flight, destroyers Yayoi and Isokaze

were outbound from Rabaul to rescue the Tsukioka Force. Allied patrol planes spotted the ships and a series of bombing missions was mounted against them. Several bombers found the ships just east of Normanby Island. Four RAAF Hudsons dropped nineteen 250-pound semi-armor piercing bombs. One of these fell close to a destroyer, probably Isokaze that suffered minor damage from a near miss. This attack may have discouraged Isokaze from aiding its companion that had been attacked as well.

A number of B-17s from the USAAF 19th Bomb Group also sought the Japanese destroyers and five heavy bombers found them. In something of a departure from normal tactics the big bombers dropped down below 2,000 feet to carry out their attacks. The Japanese destroyers threw up vigorous anti-aircraft fire and inflicted damage on some of the bombers. A total of twenty-eight 500-pound bombs were loosed against the ships and they were strafed with 50-caliber machine guns. Capt. Jack P. Thompson in B-17E, no. 41-2645, pressed his attack from an altitude of 1,400 feet. Two of his bombs hit the Yayoi while other bombs exploded close by.

According to survivors one bomb hit forward and one exploded aft causing serious damage in engineering spaces. Bursting steam pipes badly injured several of the engine-room gang and other crewmen were killed outright. The B-17s did not observe the destroyer sink but it slid beneath the waves less than ten minutes after this attack. There were many casualties among the crew but about ninety sailors survived the sinking that took place some twenty miles east of Normanby Island. Among the survivors was Yayoi’s captain, Lt. Commander Shizuka Kajimoto. Among those lost was Commander, Destroyer Division 30, Captain Shiro Yasutake. Isokaze did not remain in the area after the sinking and Yayoi’s survivors made their way to Normanby Island, most in two crowded lifeboats.

Word of the presence of the Japanese on Normanby trickled back to Allied authorities. Unarmed and without shoes or food they did not pose a military threat. ANGAU officials thought the presence of Japanese roaming the island would undermine the loyalty and cooperation of the natives. ANGAU made a request to New Guinea Force (senior Australian headquarters in New Guinea) that they be eliminated.

At dawn on September 22nd, a company of Australian troops of the 2/10th Battalion under Capt. John E. Brocksopp landed on Normanby from destroyer Stuart. Two small locally procured motor vessels aided the operation. Brocksopp’s men captured eight Yayoi survivors including seven badly injured members of the engine room crew. After dark the Australians sighted searchlights from two Japanese warships. These were destroyers Isokaze and Mochizuki engaged in yet another unsuccessful attempt to rescue Tsukioka Force. Evidence of the Japanese presence was seen and islanders admitted they had provided the shipwrecked sailors with food. They also told the Australians the Japanese had gone into the jungle with a two-hour lead. The terrain was too rough for the Australians to make up that difference in the short time allotted.

At mid-day on the 23rd Japanese aircraft appeared overhead. The Australians identified them as three Mitsubishi Type 96 bombers and eight Zeros. They passed low over the Australians (100 feet according to Brocksopp’s report) and motor vessel Kismet loaded with parts of two platoons on a coast hoping movement ran aground and the troops quickly jumped off. The Japanese aircraft made no attack but Kismet remained stuck on the beach. In the evening the Australians withdrew as scheduled. They had eight prisoners but had failed to contact the main Japanese party.

The Japanese sailors that eluded Brocksopp’s men were subsisting on coconuts, potatoes, and tapioca provided by natives. Their situation seemed hopeless but eventually they were sighted by Japanese air reconnaissance. On September 26th a return trip by Isokaze and Mochizuki was successful in rescuing eighty-three members of Yayoi’s crew.

During both successful and unsuccessful rescue attempts Japanese destroyers had passed close to the Marshall Bennett Islands. This was the group of tiny island between Woodlark and the Trobriands on which Petty Officer Murakami had landed. On several occasions Japanese rescue forces were only a few miles from Murakami’s position. Neither was aware of the other’s presence.

CONTINUED RESCUE EFFORTS. The Tsukioka Force remained isolated after the airdrop of supplies on September 12th. The supply of potatoes in the area near its positions was exhausted. Troops now had to be sent two or more miles to find potatoes. Allied aircraft were overhead on a daily basis and attacked the troops as well as native villages and even empty huts. By the 19th hope for rescue by destroyers was fading and a second “suicide squad” was sent to Buna in a sailing canoe to request rescue by landing craft from there.

Finally, on September 22nd a land reconnaissance plane appeared and announced the pending arrival of two destroyers to affect the rescue. As recounted above that mission failed. It should also be noted here that the waters in the vicinity of the D’Entrecasteaux Archipelago were extremely dangerous. They were pitted with reefs and shallows. Large vessels could operate there only with the greatest care. Taking evasive action, as for example while under air attack, was fraught with danger.

On the 23rd three land attack bombers escorted by nine Zero fighters arrived. The bombers dropped forty-four packages of rations by parachute. There was no news about an additional rescue attempt. However, the troops did learn that Port Moresby had not yet fallen to the Japanese army. From this they could infer that rescue by a relief unit from Buna was an unlikely prospect.

On the 25th a land reconnaissance plane and nine Zeros were sent to the area but they were searching for the survivors of the Yayoi not trying to establish contact with Tsukioka Force. The results of that mission are not entirely clear. Reportedly it was turned back by weather but this may apply only to the fighters. Either this mission or the mission on the 23rd discovered the location of the Yayoi survivors. They were rescued late on the 26th. On the 27th three Zeros covered the withdrawal of the rescue ships to Rabaul.

A land attack bomber and five Zeros sortied for Goodenough Island on the 29th. On board the bomber was a submarine commander trying to reconnoiter a suitable submarine route to conduct a rescue mission. This mission was turned back by weather.

On the 1st of October the waterway reconnaissance mission was repeated by a land attack bomber and six Zeros. This mission met with more success. A message tube was dropped but the troops on the ground had considerable trouble finding it.

Some of the troops, at least, were not appraised of the information contained in the errant message tube and were surprised when a submarine surfaced some distance offshore late on October 3rd. The submarine carried an MLC and its crew. For long hours the MLC brought supplies ashore and evacuated personnel, mostly wounded, from the island. A radio was also delivered but subsequent radio communication would be sporadic. Commander Eitaro Ankyu’s old but large submarine I-1 had recently been converted to transport configuration with accommodation for an MLC. When she departed Goodenough early on the 4th she carried seventy-one members of Tsukioka Force and the ashes of thirteen of their comrades who had been killed on the island.

After this re-supply mission the Japanese had tobacco in stick form as well as cigarettes. With these commodities trade with the native inhabitants of Goodenough became more frequent. Natives could supply potatoes, peanuts, bananas, papayas, and even pigs. Coconuts were apparently too commonly available to be included among trade items.

The air attacks continued. On October 7th two RAAF Beaufighters strafed buildings and native villages near Kilia Mission with 350 rounds of 20mm and 1,500 rounds of 30-caliber fire. The pilots reported damage was “unobserved.” A Japanese diarist recorded: “Air raids, as usual, are making the men jittery.”

Ten days after the first submarine rescue operation came a second. At 1830 hours on the 13th the submarine stood offshore, launched its MLC, and proceeded to load rations into the landing craft. The Japanese ashore were expecting this submarine having received radio communication concerning its arrival. They had prepared lights on the beach to guide the MLC to the shore.

Unknown to the Japanese they were not the only station reading radio traffic from Rabaul. The Allies had intercepted and de-coded the signal that detailed this mission. No. 32 Squadron (RAAF) was ordered to patrol the area. In pitch darkness Squadron Leader David W. Coloquhoun flying Hudson A16-214 sighted the Japanese shore lights before they were hurriedly extinguished. He dropped a flare. Later he dropped two 250-pound general-purpose bombs near where he had seen the lights.

The submarine submerged. The MLC proceeded to shore where it unloaded its cargo and then took on seventy passengers. The MLC cruised the bay for hours but the submarine never returned. Coloquhoun continued to patrol around the island but sighted neither the submarine nor the MLC. Later Hudson A16-202 took up the patrol but also failed to make any significant sightings. The Japanese now had additional supplies and a second MLC but Coloquhoun’s presence had completely thwarted the evacuation attempt.

The following morning four P-39s of the 8th Fighter Group searched the coast around Goodenough but the submarine had aborted its mission and was not in the area. Beaufighters strafed buildings near Kilia Mission with 300 rounds of 20mm cannon and 1,100 machine-gun rounds with “nil observed results.” Their observations offshore were also negative.

The Goodenough Island natives were trading with the Japanese but they were now also providing information on the Japanese to the Australians. Through their information, as well as through aircraft sightings, the Japanese position between Kilia Mission and Galaiwai Bay was verified, as were outpost positions. On October 19th orders were issued to send a battalion to Goodenough to eliminate the Japanese.

Lt. Col. Arthur S.W. Arnold’s 2/12th Battalion, recent veterans of the Milne Bay fighting, was chosen. The Australian infantry was transported aboard destroyers Arunta and Stuart. The main force, 520 strong under Arnold, was to land at Mud Bay on Goodenough’s east coast. A smaller force, about 120 men under Major Keith A.J. Gatewood, would land at Taleba Bay on the west coast. Arnold’s force, guided by native policemen, would march across the island toward Kilia. The plan projected that the Japanese would withdraw up the west coast to avoid Arnold’s greater numbers and become trapped between the two Australian contingents.

As the Australians were en route to land on Goodenough, the Japanese had been alerted to another means of escape. Light cruiser Tenryu and a destroyer were to be sent to rescue them. They were apparently told to scout a possible landing sight on the east coast of Goodenough removed from the point of their original landing and subsequent submarine missions. Warrant Officer Sadao Ogata, platoon leader in No. 3 platoon, No. 2 company, took nine men to the east coast and surveyed a channel between Goodenough and Ilamu Island. Late on the 22nd of October Ogata’s patrol was returning from this mission when they sighted the Australians landing in Mud Bay. Ogata sent Seaman 3rd Class Shigeki Yokota and two others back to camp to alert the main force. Ogata and the others took refuge in the jungle, probably to observe the movements of Arnold’s force or even mount a delaying action. Yokota’s mission proved redundant, as the main Japanese force had already left camp and deployed for action by the time he arrived. Between 0300 and 0330 on the 23rd a small party of Japanese encroached the Australian Mud Bay perimeter and shots were exchanged. The next morning the Australians discovered the body of a Japanese Warrant Officer near their positions.

Gatewood’s men landed at Taleba Bay in the early morning hours of the 23rd. Just before 0600 hours (0400 Japanese time) the same morning they overran a Japanese machine gun position and routed a dozen or so defenders. This raised the alarm for the Japanese. Gatewood pushed two platoons south and engaged more Japanese. The Australians drove the Japanese back beyond a place called Niubulu Creek. At this point about 0900 the Japanese counter-attacked from the north. The Australians were taking casualties and it was now Gatewood who risked being caught between two enemy contingents. He ordered his men to pull back.

Arnold’s force pushing toward Kilia from Mud Bay could make little progress during the night due to darkness, steep slopes and a driving rain. On the morning of the 23rd Arnold could hear sporadic firing in the distance but he and Gatewood were unable to communicate by radio. Arnold’s party first made contact with the enemy about 0845 hours. Sporadic enemy resistance and rough country slowed their progress on what should have been a four-hour march and by nightfall they were still a mile away from Kilia. The troops that opposed the Australians were not unarmed and barefoot like the Yayoi survivors on Normanby. Their green uniforms seemed to be in good condition. They were armed with machine-guns and mortars and did not seem to be handicapped by a shortage of ammunition.

Gatewood suffered six killed, ten wounded and three missing before withdrawing. Despite falling back, Gatewood remained under Japanese mortar and machine-gun fire. Unable to communicate by radio he sent a runner to Lt. Colonel Arnold but the prospects of the two forces coordinating their actions were nearly hopeless. By mid-afternoon Gatewood decided he would have to retire to Taleba Bay. Early on the following day he pulled out entirely and transferred his force to Mud Bay on board Stuart.

The Japanese radioed their success the following day reporting that they had repulsed the Australian attack by 1300 hours (Tokyo time) and inflicted heavy damage. Their own casualties were seventeen killed or wounded. Among the casualties was the Force commander. They also reported they were being opposed by about one hundred troops including fifty attacking from the foothills. Arnold then had about 250 of his troops in the forward area and had launched an attack on Kilia at 0910 hours (about 0720 per Japanese reports). Arnold was able to make little progress.

The Australian attack had clearly not worked according to plan. The Japanese had fought well on defense but their goal was evacuation not fighting. Prolonged fighting would eventually find them short of ammunition and could not end well. Fighting off the Australian advance was just an interim measure to leaving Goodenough.

During the 24th the Australians received no air support over Goodenough. A land reconnaissance plane and six Zeros came from Rabaul to support Tsukioka Force. This fact is worth pondering. This was the day before the Japanese all-out offensive against Guadalcanal. Most of their planes were being held in readiness to support operations in the southern Solomons. The Japanese were willing to divert a portion of their limited air resources to support a desperate rescue effort hundreds of miles from Guadalcanal. Weather was unsuitable for Allied air operations yet the Japanese got through.

The Japanese airplanes scouted the situation over Goodenough and then established liaison with Tsukioka Force. There is little doubt they provided key up to date intelligence to their comrades on the ground. After the reconnaissance plane received Australian ground fire, a Zero strafed a few huts near Mud Bay. Two Zeros then strafed the ketch McLaren King in Mud Bay. Unknown to the Japanese the little ship had Australian wounded on board. The McLaren King received several hits and fresh wounds were inflicted on some of the casualties.

Having at least temporarily rebuffed the Australian ground forces the Japanese prepared to depart Goodenough. They pulled back their troops and prepared to head for Fergusson Island. They kept Rabaul informed of their progress and attempted to establish direct contact with Cruiser Division 18 (Tenryu). The entire force and its equipment and supplies were accommodated on the two MLCs and a punt (a flat bottomed, flat sided boat apparently acquired locally). They departed after dark on the 24th and by dawn on the 25th had arrived at Fergusson Island. The withdrawal appeared to be an orderly one. When the Australians finally occupied the former Japanese positions they found no weapons or ammunition and only a small amount of canned goods and native food.

Advancing through Kilia to Galaiwai Bay on the 25th the Australians encountered no resistance and saw only a couple Japanese fleeing into the jungle. The fighting on Goodenough was over. The Australians had lost thirteen killed and nineteen wounded. They reported destroying five Japanese machine-guns and estimated they had killed thirty-nine Japanese. The Japanese losses were twenty killed and fifteen wounded. At least three of the “killed” were actually troops that were left behind and others were apparently troops killed in actions prior to the Australian landing. Two of those left behind died of disease months later and one (Shigeki Yokota) was eventually taken prisoner in July 1943.

Goodenough beach showing fake barbed wire (vines) erected by Australians - October 1942 (AWM)

Despite Allied radio intelligence and reports of natives providing information on Japanese movements, Allied air patrols failed to find the escaping Japanese. They moved in stages toward their rendezvous point on Wellen Island east of Fergusson Island. Late on October 26th two hundred sixty one troops boarded Tenryu.

On the following morning Hudson A16-205 sighted one Japanese cruiser and one destroyer far to the north headed toward Rabaul. The plane’s radio was unserviceable and so it could not make a sighting report until it returned to base. The Hudson approached the ships and encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire. It was unable to attack. Tsukioka Force made good its escape.

MURAKAMI’S DEMISE. During the weeks when hundreds of often-forlorn Japanese sailors were languishing on the islands off New Guinea’s northeast coast truly momentous events were transpiring. The strategic situation changed profoundly. In early September not only were the Japanese on the offensive in New Guinea and preparing to attack at Guadalcanal but also the Germans were in Egypt and on the outskirts of Stalingrad. German U-Boats were a much greater threat to Britain than British bombers were to Germany. The Axis offensive had reached its greatest point of expansion.

By the time the Tsukioka Force returned to Rabaul, the Japanese offensive in New Guinea had collapsed. Ill and emaciated Japanese troops were retreating toward Buna. At Guadalcanal the best offensive the Japanese could muster had been broken. In North Africa the British were on the offensive at El Alamein and Allied forces were poised to invade Morocco and Algeria. The German offensive at Stalingrad had come to a virtual standstill and Soviet forces were massing for a counter-attack. The full impact of this change would be driven into the public mind within weeks when newspaper stories and situation maps showed the Axis being thrown back on all fronts and one Allied victory following another.

Murakami knew nothing of this. Actions on Goodenough, Normanby and other nearby islands were surely minor compared to the great sweep of strategic events but Murakami remained ignorant of even these closer and, for him, more pertinent events. He maintained his resolve to get to Kitava Island and then to Kiriwina.

Through some means Murakami does not mention the “Waga” became unavailable and a new canoe had to be built. Murakami lists the names of eleven natives that were probably his companions on Iwa and involved in building the canoe. Magoru was the leader and he, at least, had his wife with him.

The “shipbuilding” took over two weeks. Two canoes were built and on one of these Murakami had inscribed on the side DAI NIPPON MURAKAMI MARU. When Allied intelligence officers later read this entry, they commented: “Murakami is fairly common, both as a place name and a surname. (An earlier P.O.W.)…who crashed on 19th February, 1942, stated he belonged to the MURAKAMI Butai.” They were completely unaware that they were reading words written by someone named Murakami.

Murakami spent part of his time observing the over flight of Allied airplanes. He recorded the type (usually Boeing B-17s or Lockheed Hudsons) as well as their course and other flight characteristics. At other times he would supervise or join in the construction of the “ships.” He was frequently impatient especially as the canoes neared completion.

In an entry dated October 6th (but which from context may relate to October 5th) Murakami wrote: “…before sunset I heard the sound of planes and bombing twice.” On October 5th an RAAF Hudson attacked a suspected submerged submarine three miles north of Kitava Island. The Hudson attacked with two 250-pound bombs. The suspected submarine might have been a whale but quite possibly it was I-1 on its return trip from Goodenough.

With the canoes completed, Murakami’s departure was further delayed by weather and native intransigence. One day it would be rainy all day and the next day would be too windy. Magoru advised Murakami that the islanders were fearful of encountering the English and did not want to leave. Murakami “thought they were saying this so as to prolong my stay.” Murakami was under the impression that “the natives cherished a deep affection for (him).”

Murakami used his enforced delay in departing to share some thoughts with the islanders. “I assembled the natives and explained that we were to join together in order to establish a new order in East Asia and that Japan was fighting with all sincerity.” According to Murakami, the “natives listened with rapt attention.” His description of the islanders’ attention is interesting since only a few days later he records: “The fact I didn’t know the language was a real shame.” When the natives would see an airplane they would ask Murakami if it was Japanese or English. He would tell them it was Japanese. According to Murakami, “pleasing the natives was no easy matter.”

Murakami mentions at one point that Magoru’s wife (“lady of the house”) spoke to him and seemed terribly worried. A few days later he had an argument with Magoru. Murakami fails to inform us as to the cause for either exchange but mentions his impatience several times and “the tediousness of the voyage and the natives.”

Murakami wrote a few short poems while on Iwa. One of them demonstrates his frustration:

“Again the setting sun finds me on a lonely island in the south seas.

“I see the enemy planes overhead: every day as a disappointed devil I came to realize my position only at death’s door. Up to now my loyalty has been insufficient.

“What face have I to return to my former unit.”

The day after his argument with Magoru, Murakami asked another islander, Bomaburu, to take him to Kitava. It is not clear whether Bomaburu was a member of Magoru’s party. He seems to have been aware of the details of Murakami’s travels and thus may have been on Gawa when he arrived there. Bomaburu apparently had no compunction about traveling to Kitava. Presumably he was able to recruit additional islanders as paddlers for the journey as well. They left Iwa on October 7th and arrived at Kitava by evening. Under the date of October 9th (actually the morning of the 8th) Murakami penned the last entry in his diary. It recorded having left Magoru and traveled with Bomaburu and the simple words: “Arrived at Kita.”

Trobriands and Marshall Bennett Islands - unmarked island is Iwa where Murakami spent most of his last days (author)

Kitava had somewhat unusual topography. Immediately behind the beach a cliff rose steeply to form a bluff reaching 300 feet in some places. Behind the bluff the terrain sloped gently downward forming a sort of bowl. Much of the island was covered by heavy vegetation.

Whether Murakami was feeling joy at continuing his journey or whether he was sad at leaving his benefactor of many days, we do not know. He was probably still wearing his flight suit and may have had his pistol with him. Unfortunately we cannot be certain of these things. We do know that he had not encountered any “English soldiers” upon landing. He seems to have spent a peaceful night on Kitava and then penned the final entries in his diary on the morning of the 8th with no indication of a sense of danger.

Before the outbreak of the war there had been a small copra operation on Kitava but the Australian planter and workers had been evacuated to Australia months before. An expeditionary unit from New Guinea Force had paid a brief visit the previous June. There was no permanent European presence on the island. However, there was a small Australian outpost at Losuia on Kiriwina and from there operatives had come to Kitava. They had a radio with them (call sign MEF WCK MXR). This party learned of Murakami’s arrival on the 7th.

On the morning of October 8th, New Guinea Force was busy monitoring reports of action in the Owen Stanley Mountains, the presence of stragglers around Milne Bay, and the troublesome Japanese presence on Goodenough Island. Among the many signals reaching New Guinea Force headquarters that morning was one from “MEF Kitava” at 1030 hours. It read:

“Japanese pilot landed here yesterday. We killed him this morning. Natives report plane came down near Gawa Island from there he went to Iwa Island (sic) and from there went to Iwa Island and from there Kitava. We are OK. Been out all night searching for him.”

The two spotters remaining on Kitava were reticent to confront the Japanese airman. On Kiriwina their commander, Capt. Whitehouse, had a feeling something was a foot on Kitava and traveled there by boat arriving 2:30 a.m. on the 8 th . The coast watchers waited until daybreak to begin their search. Whitehouse proceeded along the beach while the two spotters searched from the hill above the beach. The spotters sighted Murakami and came down the hill to confront him. When called upon to surrender Murakami responded with shots from his pistol. In the ensuing shoot out Murakami was killed.

A number of items were recovered from the nameless “Japanese pilot.” Most important was a hydrologic section map titled “Eastern Carolines to New Guinea.” The reverse side of the map contained an extensive diary. The diary and map annotations were considered important enough to be published as an ATIS (Allied Translator and Interpreter Section), SWPA, Current Translation and separately in a slightly modified form and translation in the Captured Document Series for the Allied Air Forces, Southwest Pacific. In both cases the document was said to have come into Allied hands at Milne Bay with no indication of any earlier source.

An ATIS Bulletin also contained a summary of other items “taken from JAP airman killed at Kitava 15/10/42.”

These included a table of intercommunication signals issued by the 6th Air Group on July 16th, 1942; a table with pictures and performance of American fighters; diagrams of two types of gun cameras; and, a piece of cloth marked “U SEN MURAKAMI.” No connection was made between these items and the map.

The diary was published to show something of the psychology of a Japanese pilot under stress as well as illustrate Japanese methods and impressions of Allied aircraft. Some of the other items were translated as well. Evidently no attempt was made to correlate the un-named pilot’s story with actual events over Guadalcanal.

The story of Shigenori Murakami’s combat over Guadalcanal and his odyssey afterwards has never been told. The plight of the Yayoi survivors and Tsukioka Force have been alluded to in some histories but few details of their story have been published. After more than six decades the pieces of the puzzle have been put together and we now know “the rest of the story”. Petty Officer Murakami: Rest In Peace.

—

Modified 6 Jan 2003 and 5 Nov 2004 . Special thanks to Robert Piper for providing excerpts from Powell, Two Steps to Tokyo and Perrin, Private War of the Spotters. Harumi Sakaguchi has actually visited Kitava and provided first hand information as well as details available from other sources. Thanks to these gentlemen additional details have been added to the story. It can be reported that Murakami was buried on Kitava and that there are natives on Kitava that still recall Murakami’s demise. There are surviving veterans of the 6th Kokutai that still remember their comrade of many years ago.

Below: Aerial view of the Southern Solomon Islands air battle front. Photo credit Charles Darby via LRA

And More…

After this article was posted on J-Aircraft, I received the following email from Harumi Sakaguchi of Japan regarding Murakami:

The photos below were taken about 20 years ago by Japanese diplomat Haruni Sakaguchi who visited Kitava as a result of reading my original Murakami story. All credit goes to him.

![DSCF0207[1]](https://rldunn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/DSCF02071.jpg)

Above: Murakami’s grave on Kitava Island, P.N.G.

Right: Harumi Sakaguchi with islander holding a piece of aluminum (used as a scrapper) from Murakami’s Zero drop tank

![Kitavan_remembering_Murakai_8[1]](https://rldunn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Kitavan_remembering_Murakai_81.jpg)

![Kitavan_remembering_Murakami_9[1]](https://rldunn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Kitavan_remembering_Murakami_91.jpg)

Harumi Sakaguchi with islander holding a piece of aluminum (used as a scrapper) from Murakami’s Zero drop tank

![near_where_murakami_shot_to_death[1]](https://rldunn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/near_where_murakami_shot_to_death1.jpg)

Islanders and Mr. Sakaguchi gather near where Murakami was killed.

![P9090129_R[1]](https://rldunn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/P9090129_R1.jpg)

Photo of Shigejiro Murakami at his brother’s home in Japan.

![witness_-left-to_death_of_murakami_keijiro[1]](https://rldunn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/witness_-left-to_death_of_murakami_keijiro1.jpg)

On left – an islander that witnessed Murakami’s death.