With January 1944’s campaign in full swing, P‑38J and H Lightnings—freed from their early teething troubles—joined Corsairs, Hellcats, and Kittyhawks in high‑altitude escorts and fighter sweeps from Bougainville to Rabaul’s Gazelle Peninsula. Yet raw speed and twin‑engine firepower only went so far: fickle weather, extreme range, and tangled scissoring tactics meant claims far outpaced confirmed kills and formations often splintered in the maelstrom. In this second installment, we’ll explore how the Lightning both asserted its might—and revealed its limits—against Rabaul’s fierce defenses during the pivotal mid‑January offensive.

Lockheed P-38 Lightning

The introduction and early operations of the Lockheed P-38 in the South and Southwest Pacific theaters were explored in a previous article. Here, we review later operations when teething issues with the Lightning had been overcome and optimum tactics developed. In combat, optimum conditions do not always exist, and preferred tactics cannot always be employed. The Lightning’s role in air campaigns against Rabaul, New Britain—the key Japanese base in the southern Pacific region—permits exploration of later operations.

The Lightning’s part in the Fifth Air Force October–November 1943 campaign against Rabaul was explored in the author’s article published in the journal Air Power History. A copy can be found at Shootout at Rabaul – Free Online Library. In that campaign, the first mission on 12 October 1943 was flown by 125 P‑38s; but, for a maximum effort on 2 November, only eighty Lightnings were available. Soon thereafter, two squadrons converted from P-38s to P-47s due to a shortage of Lightnings—this even though new P-38s were arriving in October and November. Pre-campaign strength was not restored until March 1944.

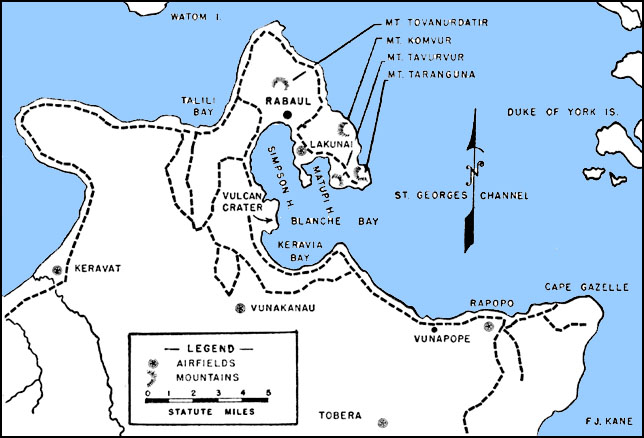

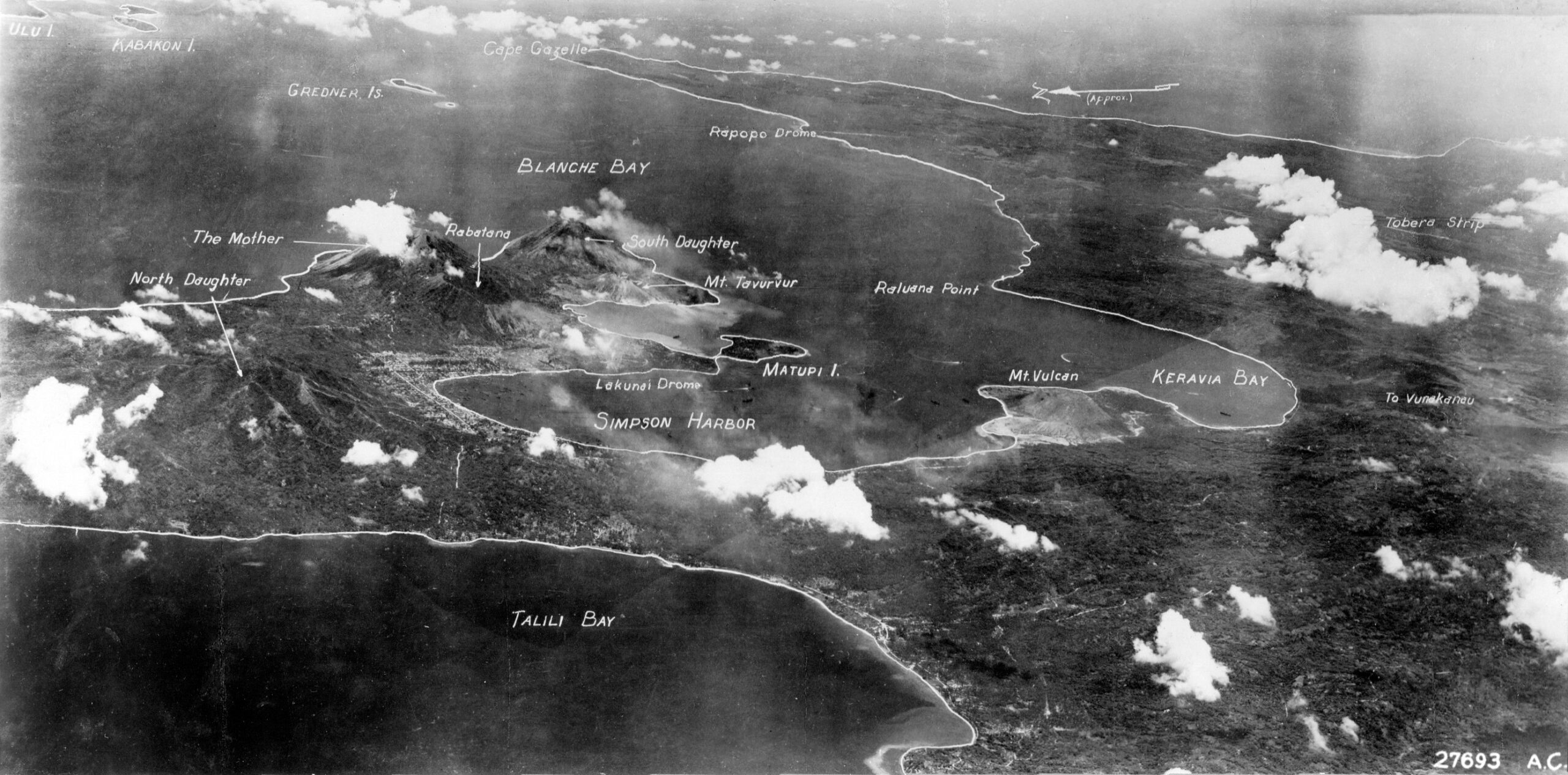

Rabaul Map

Our primary focus is on the Lightning in the Air Command Solomon Islands (ComAirSols) campaign against Rabaul in late 1943 and early 1944, concentrating on the mid-point of the campaign in January 1944. Fighter missions against Rabaul from the Solomons were made possible by the development of airfields on Bougainville Island in the northern Solomons. The P‑38s could fly missions with a margin of safety from as far afield as Munda (380 miles) or Stirling Island (285 miles), but the campaign was not feasible without other fighters participating in fighter sweeps and escort duty.

In the Fifth Air Force campaign against Rabaul, the P‑38 was the only U.S. fighter involved. In the ComAirSols campaign, the P‑38 was in the minority of a fighter force that included U.S. Marine F4U Corsairs, U.S. Navy F6F Hellcats, and New Zealand Kittyhawks (late-model P-40s). The 44th Fighter Squadron, a veteran of P-40 operations, reequipped with the Lightning in November—adding a few trained P‑38 pilots to pilots who had converted from the Warhawk. The squadron flew several combat missions in early December but was not included in the first mission of the campaign, a fighter sweep on 17 December. A veteran P-38 squadron, the 339th FS, was at a rear-area base resting and training during December and the first part of January 1944. Meanwhile, the 44th joined the campaign for some of the December missions. On 24 December, sixteen Lightnings of the 44th claimed eight Zekes destroyed without loss; two pilots (Maj. Robert Westbrook and 1Lt. Byron Bowman) each claimed three. These were Bowman’s only victory credits; Westbrook’s kills brought his score to twelve of an eventual twenty. However, on that date, total Allied fighter claims numbered twenty-five, but only five Japanese fighters were shot down—over-claiming by five to one proved to be the average for Allied fighters during the campaign. Japanese over-claiming was typically even worse.

The following day, the 44th FS claimed four victories but lost two P‑38s and their pilots. Another crippled Lightning crash-landed on Barakoma strip, Vella LaVella, and a fourth ended up on a beach near Torokina. Total claims were for thirteen Japanese fighters, as opposed to Japanese records showing three lost.

Robert Westbrook – his P-38J show score after Rabaul campaignJapanese air efforts from mid-December 1943 to early January were divided between offensive efforts countering Allied amphibious operations at Arawe and then Cape Gloucester in western New Britain, as well as the aerial defense of Rabaul. Japanese fighter pilots consisted of a mix of veterans, newcomers, and a few top aces. Among the latter was Petty Officer Tetsuzo Iwamoto. Iwamoto arrived at Rabaul in November 1943 with a detachment from Air Group 281 that was incorporated into Air Group 204. Later, he transferred to Air Group 253 and was among the pilots withdrawing to Truk in February 1944. Iwamoto claimed many kills over Rabaul, but the only officially recorded victories were twenty when he was serving with Air Group 204; his victims reputedly included four P‑38s.

Tetsuzo Iwamoto

Lightnings over Rabaul January 1944

With the arrival of January 1944, the campaign increased in tempo and intensity. In addition to fighter sweeps and B‑24 heavy bombers, attack bombers (SBDs and TBFs) and, later, medium bombers (B‑25s) joined the attack. The Lightning squadrons were flying P‑38J and some P‑38H models. Their opponents were primarily flying the Zeke, Type Zero carrier fighters models 21 (Nakajima-built) and 52. The model 52 was the latest version in production from August 1943, but the model 21 was essentially the same fighter introduced to combat in China in 1940. By early 1944, only a few model 22s were operationally available. Despite many Allied pilot “sightings” of Hamps, the Zero 32 was a non-factor. Combined totals of operational fighters for Air Groups 201 and 204 on 1 January 1944 were: Zero 21 – 22; Zero 22 – 5; Zero 52 – 30. Air Group 253 had a total of 30 Zero 21s and 52s operational. Another anomaly of Allied “sightings” were relatively frequent reports of Tonys (Japanese Army Type 3 fighters). No Japanese army fighter units were stationed on New Britain. The Japanese navy’s in-line engine Suisei carrier bomber (Judy) was in the area and sometimes engaged in interceptions dropping air-burst bombs; however, its occasional presence cannot account for all Allied misidentifications and claims for Tonys. This attests to the fact that what pilots reported they saw in the heat of combat did not always form a true picture of actual events.

P-38H

On the first day of 1944, twenty-eight P‑38s were among the fighters escorting B‑24s to Rabaul. Some of the flights engaged in inconclusive combats with Zeros, but the 44th FS returned without claims or losses. For a few days thereafter, P‑38s were not involved, turned back due to weather, assigned other duties, or otherwise saw no combat.

The P‑38 burnished its reputation in the South Pacific on 6 January. Twenty P‑38s from Stirling base on Mono Island joined thirty-two Corsairs and twenty-six Hellcats over Torokina in a fighter sweep to Rabaul. Weather was rough, and only sixteen P‑38s and eight Corsairs got to Rabaul. Their opponents were thirty-three Zeros from Air Group 253. Among the P‑38 pilots was Lt. Col. Leo F. Dusard, new CO of the 347th Fighter Group, flying as wingman to Westbrook in the first flight. Originally scheduled to fly at 28,000 feet, the P‑38s approached Rabaul at 17,000 feet due to weather conditions, although once over Rabaul some of the P‑38s climbed as high as 25,000 feet. Most of the combat took place between New Ireland and the Gazelle Peninsula over St. George’s Channel. At altitudes of about 14,000 feet, the Lightnings claimed Zeros shot down in head-on passes and from directly astern. Ten Lightning pilots claimed sure or probable victories, among them Lt. Col. Dusard who claimed one Zeke and returned on one engine in a badly shot-up Lightning. Westbrook claimed a certain and two probables. Total claims ran to nine certain and six probable. In the official post-war list (U.S. Air Force Historical Study No. 85), in addition to Dusard and Westbrook’s claims, official victories are credited to 1Lt. Richard Wheeler (2), Capt. Howard Dreckman, and 1Lt. James Long, totaling seven. One P‑38 was seen to crash flaming into the sea (1Lt. Travis Wells), and the pilot of another was seen to bail out (2Lt. Robert Stoll) with no confirmation that a parachute opened. Corsairs claimed one victim. Air Group 253 pilots claimed eight P‑38s and two F4Us; one Zero was shot down and one force-landed (apparently a write-off). Three other Zeros took machine-gun hits; some of the Lightnings were also damaged. In any event, the result of the combat was that each side lost two fighters—not five to one in favor of the Americans, as claims would suggest.

On 11 January, sixteen P‑38s were among the escorts of SBDs and TBFs. Unable to attack shipping, installations at Cape St. George, New Ireland, were attacked. The sixty-eight escorting fighters effectively protected the attack bombers. P‑38 claims were for one certain and four probables; the victor was Capt. Frank Gaunt, his eighth. Although Zeros were reported to go down flaming or smoking, none was seen to crash. Air Group 253 reported encountering sixteen P‑38s, claimed one, and reported no losses.

P-38J without camoflage paint

Perspective at mid-month

As January wore on the line-up on each side changed. For the Japanese Air Group 201 left for rest and reequipment on Saipan. Plans were afoot to bring in reinforcements from carrier based air groups later in the month. On the Allied side the 339th FS under CO Maj. Henry Lawrence joined the battle. For a short time before the 44th left for rest two P-38 squadrons were in operation. Events at mid-month in January provide interesting perspective on other units and shed light on their Japanese opponents.

January 14 saw the first shipping strike for Marine attack aircraft. Fifty-two strike aircraft were escorted by seventy-six fighters. Escort cover was allocated as follows. High cover – 16 F4Us, medium cover – 16 F4Us, low cover – 16 F4Us and 8 F6Fs, close – cover 20 Kittyhawks. The Japanese apparently had good radar warning on this occasion with the initial interception by an estimated thirty fighters over Duke of York Island on the approach to Rabaul’s harbor. Additional fighters joined in over New Britain with the total engaged estimated to be up a hundred. Few got through to the strike aircraft with much of the combat being with the high cover after it descended to about 14,000 feet to cover the attack dives of the strike aircraft. Fighter claims ran to twenty-seven with TBF gunners adding two more. Sixteen probables were also claimed. Marine squadron VMF-215 claimed nineteen victories including five by Capt. Robert Hanson. Two of the squadron’s pilots failed to return and another bailed out of an aircraft too badly damaged to land at Torokina. Admiral Nimitz’ monthly report placed total combat losses at six Corsairs, two Hellcats, a TBF to fighters and an SBD to AA. Eighty-four Zeros intercepted. Japanese losses were three Zeros missing or crashed and seven damaged. Although the 44th FS did not take part in the escort mission to Rabaul on this date, it was not inactive. An afternoon patrol encountered a Japanese intruder identified as a Kate (“unidentified” in later intelligence summaries; possibly a Type 2 carrier recon plane) near Torokina and shot it down. Capt. Cotesworth Head was credited with the victory.

On 15 January Japanese Air Group 204 reported having fifty-five operational Zeros and forty-five operational pilots. Air Group 253 reported thirty-seven operational aircraft and twenty-nine operational pilots. Total numbers for both aircraft and pilots were considerably higher than operational figures. For a pilot to be considered operational he had to be healthy and have a skill rating of either A, B, or C. Comparing the number of Japanese fighters intercepting Allied raids with operational pilots suggests that pilots not considered operational were manning some of the aircraft. A category C pilot was one who had completed full operational training but not yet obtained 400 hours flying time. There was also a category D. These were pilots who had not completed a full course of operational training but had been sent to operational units to complete their training. This was done because Japan was trying to rapidly increase its stock of pilots. Training bases in the Homeland and occupied territories were oversubscribed and experienced instructors limited. Allied pilots flying missions to Rabaul were confronting not only Japanese fighter aces and journeymen pilots, but pilots with limited expertise and exposure to combat techniques. The experienced pilots were being worn down by the high tempo of operations with little rest. In addition to day attacks whenever weather permitted night bombing by heavy and medium bombers was a regular feature of the campaign at this point.

On the 16th a major ComAirSols raid was thwarted by weather with only a few Corsairs coming within sight of Rabaul. None the less the approaching Allied planes flushed over eighty Japanese fighters from their bases at Vunakanau and Tobera. Combined with a dawn patrol Japanese fighter pilots flew ninety-five sorties that day when only seventy-four pilots were considered “operational.” Veteran Zero pilots were experimenting with new techniques. Some Japanese pilots seem to have adopted a method to counter Allied weaving or scissoring tactics by attacking at the outside extreme of the weave maneuver negating mutual protection.

U.S. intelligence succeeded in intercepting and translating a Japanese message that contained a record of naval aircraft lost to all causes in Japan’s Southeast Area (mainly Rabaul) from 1 to 15 January 1944. It was compared to U.S. claims during the same period. U.S. claim/reported Japanese loss was for fighters 170/30; single-engine bombers 1/9; medium bombers 5/4; other 17/1. Total 193/44. The reported losses in fighters and single-engine bombers tracks closely with a report of the 26th Air Flotilla which operated those types during the same period – 29 fighters and 9 dive, attack, and reconnaissance bombers lost.

Late January Missions

With the 339th FS back in the forward area it joined the 44th for a joint mission to Rabaul on 17 January. The mission called for six flights of four P-38s each. Capt. Head of the 44th led the first flight and 1Lt. Hart of the 339th led the second flight. Eighty fighters would escort forty-eight Marine and Navy strike aircraft SBDs and TBFs. The escort assignments were high cover – 16 P38s; medium cover – 8 P-38s and 8 F4Us; low cover – 24 F4Us; close cover – 16 F4Us and 8 F6Fs. After dropouts seventy fighters covered the attack aircraft over the target. Five of the dropouts were Lightnings. Lightnings of the high cover were at 17,000 feet and the medium cover was at 15,000 feet when the dive bombers began their dives from 9,000 feet. The first eight Zeros sighted began their attacks from about 19,000 feet. They were soon joined by others of the seventy-nine Zeros the Japanese scrambled.

A 44th FS report described the combat:

Our (19) P-38s were scissoring as the first Japs came peppering through. We held to the scissoring pattern for about a minute…but as the main body of Zekes came tearing in, individual fights developed and flights became separated in taking cover in cloud layers. This running fight stretched from Simpson Harbor to Cape Gazelle. During the melee three of our pilots were seen to crash in the water. Later five others turned up missing.

Capt. C.B. Head, a flight leader and one of our best flyers got three Zekes that day – half our total bag. He also made an effort to reform us at the rally point southeast of Cape Gazelle but things were so hectic that most of us had to make a fighting withdrawal as best we could.

The shipping attack sank three cargo ships and badly damaged a fourth. Several lesser vessels were sunk or damaged. In addition to three Zekes claimed by Capt. Head one each was claimed by 1Lt. Robert Corbett of Head’s flight and 339th pilots 1Lt. Jarrold Lilliedell and F/O James Kennedy. In addition to the Zekes claimed by the P-38s Marine Corsairs claimed ten and a TBF gunner claimed one. Eight P-38s were lost, four from each squadron. One each F4U, F6F , SBD and TBF were also lost. The Lightnings appear to have borne a significant portion of the action.

Their opponents were from Air Groups 204 and 253. Forty-three Zeros from 204 led by Lt. Sadao Yamaguchi claimed an amazing 29 P-38s, 12 F4Us, 3 F6Fs and 7 strike aircraft as certainly destroyed. Eight of its Zeros were damaged. Leading light was Superior Seaman Noritsura Kodaka who was credited with three P-38s and awarded three bottles of choice sake by the commander of the 26th Air Flotilla. Thirty-six Zeros from 253 led by Lt. Kenji Nakagawa claimed 10 F4Us, 7 P-38s and one F6F. Four of its Zeros were damaged. It appears neither air group suffered serious injury to any of its pilots.

44th FS pilots lost: 1Lt. Earl Heckler and 2Lt. Theordore Schoettel both seen going down in flames shot down by enemy aircraft; 2Lt. John Munson last seen in vicinity of Blanche Bay and 2Lt. George Snell last seen off southwest coast of New Ireland cause of loss unknown.

339th FS pilots lost: 1Lt. Gifford Brown crashed in Blanche Bay; 1Lt. Glen Hart bailed out off New Ireland and rescued by a PBY after a week; 2Lt. Charles Black last seen over Blanche Bay; 2Lt. John Langen seen going down in flames.

Nice view of captured Zero 52

The mission on the January 17 seems confused in the sense that both sides seriously over claimed. The mission the following day was confused in execution by both sides. The mission was planned to be a low level attack by thirty-four B-25s covered by seventy fighters with P-38s as the high cover. As carried out most of the fighters got to Rabaul late with fourteen P-38s dropping to low level to provide the only cover for the B-25s over the target. The Japanese scrambled over eighty fighters but only half of them got into action. A report from a Lightning pilot:

Going in on the deck with the bombers, we were jumped right after the run by 20 to 30 Zekes. This time we knocked down 6 Zekes sure – all off somebody’s tail – but Capt. Head got an engine shot out and had to leave the fight. Jim Reddington [Capt. James Reddington] took over…training really paid off. We scissored back and forth over the Mitchells. The 25s helped us a lot…fastest, tightest rendezvous you ever saw…Capt. Head is missing.

Capt. Head was credited with shooting down a Zeke in a head on pass before being attacked by two Zekes from behind. He was last seen five miles offshore with his right engine smoking. For an interesting theory concerning his survival and ultimate demise see pages 523-524 of South Pacific Air War. In addition to Capt. Head one B-25 was lost. Capt. Reddington claimed three victories with Lieutenants Robert Connolly and John Roehm credited with one apiece. B-25 gunners claimed four Zekes. Once the Navy and Marine fighters got into action they claimed a dozen fighters identified as Zekes, Hamps and Tonys. Air Group 253 scrambled thirty-nine Zeros and claimed four P-38s and a B-25. Four of their Zeros were missing after the combat. B-25 bombs destroyed one plane on the ground, badly damaged another, set a fuel dump on fire.

B-25s over Rabaul

There was no big raid on the following day but on the twentieth eight 339th FS Lightnings were part of the seventy fighters escorting B-25s to Rabaul. The Japanese scrambled eighty fighters. The Corsairs saw most of the combat claiming fourteen victories. Resistance was assessed as ‘stiff’ in the South Pacific Command war diary. Two B-25s were lost along with three Corsairs. The 339th lost Lieutenants Dwight Kelly and Charles Smith and made no victory claims. The Japanese routinely carried out night attacks against Allied positions with small numbers of bombers. On this night they sent five Type 1 land attack (Betty) bombers to attack Torokina and Mono Island. At Torokina bombs caused five personnel casualties and destroyed a machine gun position. At Stirling, base of the 339th and other units, they destroyed two B-25s and damaged eight others. A Navy PV-1 night fighter gave chase over Torokina but failed to down any of the bombers. Admiral Nimitz monthly report summarized results of Japanese night raids. “These attacks particularly during the middle of the month were more destructive than usual. Our losses were 9 killed, 59 wounded, 6 planes destroyed and 10 more damaged.”

On 22 January there was another big raid. Twenty-seven B-25s were escorted by more than ninety fighters including P-38s of the 339th FS. The Lightnings claimed no victories and lost two pilots, one in an unusual fashion. A gunner on a B-25 observed the incident. His report is paraphrased:

Saw aircraft possibly 6,000 feet above P-38 release object which exploded right in front of the P-38 showering many tentacles. P-38 flew right through the main part. Possibly fifteen seconds later, noticed white smoke from each engine. Not five seconds later both engines burst into flames soon enveloping the whole leading edge. It spun into the water two miles from Duke of York Island.

Thus, is recorded the demise of 2Lt. Frederick Seaman. The other loss was 2Lt. Edwin Studley who had the good fortune to be rescued by a VP-14 PBY. Most likely Seaman fell to one of the half dozen pilots of Air Group 253 that dropped 30kg air burst bombs on this occasion.

Also on this date the Japanese made the decision to relieve the 26th Air Flotilla of responsibility for the air defense of Rabaul. The decision would take effect within days and result in the flotilla headquarters and Air Group 204 leaving Rabaul. The 2nd Aircraft Carrier Division would take over the defense of Rabaul with the main elements of air groups from the division’s three carriers: Junyo, Hiyo, and Ryuho. Fighters would go to Vunakanau, carrier combers to Tobera and attack bombers to Kavieng on New Ireland. Air Group 253 would remain at Rabaul and continue its air defense role.

On 23 January during another big ComAirSols raid the Japanese fighter groups claimed fifty-one kills including seventeen uncertain. Six of the claims were for P-38s. Three U.S. fighters were lost including one Lightning flown by 2Lt. Arthur Yeilding. 1Lt. Kenneth McCloud claimed one Zero for the Lightning squadron.

Rabaul early 1944

A shipping strike on 24 January saw eighteen TBFs escorted by eighty-four fighters including nine P-38s. The strike force was jumped by a reported forty Zekes. This was the swan song for Air Group 204 and their twenty-six Zeros were the apparent opponents of the 339th FS claiming two P-38s among their sixteen reported victories. No Lightnings were lost. The 339th claimed four kills. Two by 1Lt. Truman Barnes and one each by Capt. George Chandler and 2Lt. Thomas Walker. All three pilots attained ace status. Air Group 204 reported one Zero force landed an apparent write off and another heavily damaged.

On the twenty-fifth most of the Zeros and pilots of Air Group 204 flew to Truk. Air Group 253 received several pilot transfers from Air Group 204. Sixty Zero model 21s and eighteen Type 99 model 22 carrier bombers of the 2nd Carrier Division took up residence at Rabaul area air bases. The fighters were under the overall command of veteran Lt. Cdr. Saburo Shindo who had led the Zero fighters in their very first combat over China in September 1940.

During attacks on 26 and 27 January there was heavy air combat not involving the 339th FS. Regarding the twenty-sixth an intelligence report stated “Apparently reinforced, as indicated by the sighting of planes with entirely different paint jobs in the air, the enemy put up a stiffer fight…” For the twenty-seventh these comments were recorded, “The arrival of new enemy fighter strength was timely as in the last few days his capabilities for interception had weakened in quality and quantity…”

January 28 brought additional claims and losses for the 339th. There were raids in the morning and afternoon. Twelve Lightnings were part of the escort for SBDs and TBFs attacking Tobera airfield in the morning. Capt. Kenneth McCloud was firing on a Zeke when it reportedly collided with another Zeke, and he received two victory credits. Claiming single Zeros were Capt. Stanley Waldon, 1Lt. Donald Stewart, and 2Lt. William Thomas (Waldon’s claim does not appear in the official post-war list). McCloud and his wingman 2Lt. Thomas Benim were in the squadron’s top cover flight when Zeros jumped them. Benim was hit and attempted to join the bombers for cover. While joining his wingman McCloud was attacked by a Zeke which resulted of a series of combats in which he claimed two victims but was badly shot up and eventually ditched. Lieutenants Benim and William Thomas also ditched and were rescued the same day by a VP-17 “Dumbo.” McCloud survived nine harrowing days under difficult conditions in his raft before being rescued. Lieutenants Adam Stewart and Garland Schock failed to return and were deemed killed in action. During the morning combat Allied fighters claimed 26 Zekes, two Hamps, and a Tony. Japanese losses were six failed to return and two heavily damaged (likely write offs).

Final Lightning action for the month came on the thirtieth when Rabaul was hit with multiple raids. Fifteen Lightnings were among the escorts for eighteen B-24s bombing Vunakanau airfield. Only four enemy fighters were sighted and only one made an ineffective pass at the bombers. Junyo Zeros claimed one P-38, but none was lost. A post-mission intelligence summary inaccurately stated P-38s downed three Zekes, but no victory credits appear in the post-war list.

The verdict of history

The Fifth Air Force campaign against Rabaul October to early November 1943 was supposed to “take out” Rabaul, that is neutralize it to pave the way for the Bougainville invasion. On the first day of the Bougainville invasion Rabaul sent more than a hundred fighters and dive bombers against the ships and the beachhead at Empress Augusta Bay. This was followed by a naval battle in which the Japanese sortied two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers ands six destroyers from Rabaul. These efforts were not particularly successful but demonstrated Rabaul had not been taken out or neutralized. P-38s provided the fighter escort for the bombing attacks. While the fighters were not directly responsible for the damage, or lack thereof, done by the bombers they were an integral component of the campaign. The aerial defenses of Rabaul had not been overcome. Moreover, the Fifth Air Force P-38 force had to undergo serious reorganization after the campaign due to outright losses suffered, damage in combat and general wear and tear on its aircraft. Seldom is this pointed out as a defeat, nor does it reflect negatively on the P-38. Rather overstated P-38 claims exceeding outright losses allow this episode to be portrayed as a victory not a negative on the P-38’s reputation.

Considering the facts revealed in this article about P-38 losses versus victories in the ComSoPac December 1943 to February 1944 campaign against Rabaul, why hasn’t this dampened the P-38’s reputation? Eight P-38s lost with no compensating victories sounds like a major defeat. Again, it seems that the victor controls the narrative in the immediate aftermath of events. History seems slow to catch up. Here is snapshot of how the P-38’s role was portrayed in a paragraph from a lengthy narrative penned shortly after the events covered in this article.

Between December 19 and February 25 our Lightnings flew 690 sorties to the Rabaul area…We knocked down 65 Jap fighters during the campaign and listed 19 more as probables. Our own loss was 22 Lightnings, with five pilots being rescued by Dumbo. That’s a pretty good score in any league, but here’s the payoff: In 40 bomber escort missions (935 sorties) covered by our P-38’s, not a single bomber was shot down by some 900 enemy fighters we encountered. The 38’s failed to bring home only 11 bombers – all hit by ack-ack.

The statement about no bombers being lost to fighters while escorted by P-38s is simply wrong. As to 65 P-38 certain victory claims perhaps a dozen reflect actual Japanese losses.

The P-38 certainly showed its value on many occasions. It also had serious limitations. In the campaigns against Rabaul the P-38 escorted high, medium and low altitude bomber mission. That was the job that needed to be done. The P-38 might have been relegated to strafing Japanese barges or attacking isolated pockets of forlorn Japanese ground troops. The P-39 could fly those missions. The P-38 flew high priority missions and was found wanting, something official histories and many other accounts have failed to admit.