Next up in the How Great series is the P-38. “P-38 Lightning Might Have Been the Best Fighter of World War II” and “P-38 Lightning WWII’s twin engine wonder” or even “Unsung Hero of WW II” read headlines of articles on my computer homepage. Whatever deficiencies might have been evident in the P-38’s service as an escort fighter in Eighth Air Force operations over northern Europe, there is an impression that its service in the Pacific was an unbroken string of successes. Most aviation aficionados recognize the Lightning as an icon of the Pacific Air War from late 1942 through 1945. From the very beginning of its service over the Pacific the P-38 was appreciated for its high altitude performance and long range. The P-38 was also valued for its potential as a fighter-bomber either carrying two bombs or a bomb and an external fuel tank. It appears that initially it was assumed the P-38 could perform the missions being flown by P-39s and P-40s as well or better than those fighters. In this examination of how great we focus on early operations of the P-38 displaying shortcomings in certain operational scenarios as well as the over claiming that contributed to its iconic reputation. We include a few examples that show the P-38’s limitations were also evident in later operations.

The Arrival and Early Missions of P-38 Lightnings in the Pacific Theater

General George Kenney, commander of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific and U.S. Fifth Air Force, lobbied for P-38s to be supplied to his command. In September of 1942 they were on their way. Another beneficiary of his efforts was the Army air component of the South Pacific Command. Some of the P-38s were diverted to New Caledonia in October. In Australia the P-38s were erected and test flown. Technical glitches were worked out. Several pilots with P-38 experience were assigned to squadrons of the Fifth Air Force. A transition and training unit, 17th Fighter Squadron (Provisional), was temporarily established to provide P-38 experience to pilots unfamiliar with the aircraft. In the South Pacific the recently formed 339th FS received the Lockheed fighter and combat-experienced pilots were assigned and given a brief period of familiarization before heading to Guadalcanal.

On 12 November 1942, eight P-38 Lightnings of the 339th FS, led by Maj. Dale Brannon, arrived on Guadalcanal. Three others followed a few days later. Brannon led the original contingent of P-400 Airacobras to Guadalcanal in August and achieved three victories in the maligned Bell fighter. On the 14th, Capt. Robert Faurot led a detachment of eight 39th FS P-38F’s via Milne Bay to support the 339th. Despite monumental sea battles and many air attacks raging in mid-November, when the 39th returned to New Guinea after a week, all its patrols had been routine. On the 15th, Brannon led the 339th Lightnings in their first mission from Guadalcanal with no enemy contact. The naval battles of Guadalcanal ended with no successes for the Lightnings. The first victory claims followed soon after.

South Pacific, November 1942 to February 1943

The first combat and first claims came on 18 November during a strike against shipping at Tonolei harbor, southern Bougainville Island. This was the first time bombers were escorted by fighters to Bougainville 300 miles from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The strike was made up of eleven B-17s, four B-26s and eight P-38’s (one returned early). P-38 pilot Capt. William Sharpsteen reported: “We escorted B-17’s in over their target at about 16,000 feet, the B-17’s were at 12,000 feet. The Zeros were not in the air when we got there but climbed very fast. We shot down three Zeros. We were very fortunate that we had altitude over the Zeros and that they were not already in the sky.” Rising to meet the American formation were an estimated thirty plus interceptors described as “square wing Zeros, Zero float-planes and float biplanes.” Their opponents were six Zeros (Hamps) from Air Group 204, four Type 2 fighter floatplanes (Rufe) of Air Group 802, and several Type Zero observation floatplanes (Pete) from air groups of R-Area Air Force. The Petes, while useful observation planes and the bane of PT boats, mounted only two forward firing 7.7mm machine guns and had a maximum speed less than 250 m.p.h. The opposing fighters clashed while the bombers proceeded with their bomb runs. 1Lt. Deltis Fincher was credited with two Zeros and 1Lt. James Obermiller with one. Hits were also claimed on a float biplane. Although one Zero of Air Group 204 went down it is not certain it fell victim to the P-38s. B-17 gunners claimed ten Zeros and two floatplanes. The B-26s claimed two victories. On the initial bomb run the bombs of the lead bomber hung up. The lead flight circled to make a second run. The second flight abandoned the mission eventually dropping bombs on Munda. The P-38s stayed with the second flight of B-17s and missed out on the extended combat between the first flight and Zeros which resulted in one B-17 going down after a combat of nearly half an hour covering seventy miles to a ditching off Vella Lavella. A second B-17 returned to Guadalcanal badly damaged. All the P-38s returned, one sporting several cannon and machine gun hits.

P-38 on Guadalcanal

After this mission the Lightning pilots got time to settle in at Guadalcanal while 339th pilots who had been flying P-39s got flying time on the P-38. The Japanese mounted no day raids against Guadalcanal for the rest of the month. They had shifted fighters of Air Groups 252 and 582 to Lae for air defense and to support ground operations in the Buna area of New Guinea. Other Zeros were stationed at Rabaul. There were only a dozen or so Zeros of Air Group 204 operating from Buin in late November. The Guadalcanal Lightnings stood alert or flew routine missions.

The P-38s were involved on the fringe of actions such as on 8 December when they joined F4Fs and a P-40 escorting thirteen SBDs to attack Japanese destroyers near Munda. The destroyers had an air cover of eight Type Zero observation floatplanes. An SBD was lost but the P-38s suffered no damage and made no claims. The following day P-38s flew a special reconnaissance to the Buin area to check out reports of an aircraft carrier in the vicinity. The Lightnings returned to report no aircraft carrier but provided detailed observations of shipping in the area.

On 10 December a mission to southern Bougainville was much like the 18 November mission. Eight P-38s escorted eleven B-17s. Once again the Japanese were caught by surprise. The B-17s had bombed and were leaving the area before Japanese fighters climbed to intercept. The P-38s were at 18,000 feet with a top cover element at 23,000 feet. Six Zeros, two seaplane fighters and a few float biplanes intercepted. P-38s claimed three Zeros and two seaplane fighters. One Zero of Air Group 204 was shot down with its pilot killed and a second force landed. All the B-17s and P-38s returned to Guadalcanal. One P-38 was badly shot up with its pilot slightly wounded. A second was less seriously damaged. In other combat that day Zeros caught a search B-17 over New Georgia. The badly damaged bomber returned to Guadalcanal on two engines with dead and wounded crewmen aboard. On the 19th seven B-17s were unable to bomb Kahili due to weather and bombed Munda instead. The Japanese airplanes that intercepted them over Shortland Island were mostly Pete float biplanes. Only four Zeros from Air Group 204 were involved. Five P-38s were at 18,000 feet with three others as top cover. The P-38s claimed two biplanes and the B-17s claimed one. All the U.S planes made it back to Guadalcanal but two P-38s were seriously damaged.

During the last week of December there were numerous raids on Munda’s recently operational airfield. Heavy bombers, attack bombers escorted by various fighters were involved. Numerous Zeros were claimed in the air and on the ground. The P-38s participated in these missions. They suffered no losses and made no claims. Zeros of Air Group 252 claimed a P-38 kill on December 23rd.

Overall these early missions seemed to be a net positive for the P-38. General Harmon Army South Pacific air commander thought the P-38 had done well in its early missions. However, it is noteworthy that the P-38s encountered only small numbers of Zeros on these missions and their victory claims included floatplanes. The reaction of the pilots that flew these missions was generally less than positive, although the P-38’s high altitude performance, range and armament were viewed positively. Interestingly, several pilots characterized missions flown at 18,000 feet or above as low altitude missions.

The following are comments by pilots of the 339th FS who flew P-38 missions in this period including the missions described above. “The P-38’s are not good escort ships for low level bombing. There is very little advantage of speed below 20,000 feet, the visibility below is poor, and maneuverability is poor.” (1Lt. Edgar Barr). “Those of us that have 200 hours in a P-40, believe that that ship would be more suited for escort missions, within its range, against Zeros, due to better visibility and maneuverability.” (1Lt. Danforth Miller). “From my experience I have found the P-38 is not a low altitude fighter. We do, however, have a slight speed advantage over the Zero. The visibility of the P-38 is very poor therefor if used for escort, it should be used at its best altitude of 25,000 feet or higher. In my estimation it would make a very good bomber interceptor.” (1Lt. Edmund Brzuska). A pilot who indicated he liked the P-38 also had this to say: “The P-38 has…two bad characteristics, poor visibility below and bad dive characteristics. The P-38 is a good interceptor and good high-altitude escort ship, but it is a poor low altitude escort plane.” (1Lt. Douglas Canning). “I found it very difficult to try to do a quick maneuver in a P-38 to try to follow or get a lead on a Jap plane. When putting strong pressure on the controls, the plane will shudder making it very difficult to get a good aim. It is impossible to maneuver fast enough to follow the dodging and turning of Jap planes. It is also very blind. The large wings and engines make it impossible to see to one side and underneath and vision to the rear is only fair. All in all, the P-38 in my opinion is too big and heavy and hard to maneuver to fight like we had to, around 15,000 feet and under. We did not have a chance to use them against high altitude bombers for which it was made. It is probably OK for that work, I hope.” (1Lt. Albert Farquharson). “The action at Guadalcanal having passed to the offensive, the P-38’s were used as escort. SBD escort was necessarily at very low altitude, fortunately we had no contacts; I say fortunately, because I feel we would have had as much loss as the enemy at that altitude.” (Maj. Dale Brannon).

January 1943 brought a mixed bag of combat encounters during escort and interception missions for the P-38. An escort mission to Bougainville on 5 January by five B-17s and seven P-38s resulted in the first P-38 combat losses in the South Pacific. Six Zeros of Air Group 204 and two seaplane fighters of Air Group 802 intercepted along with several float biplanes. The Americans estimated twenty-five in total. The Lightning pilots claimed two Petes and a float Zero plus additional probables. Air Group 802 lost a Type 2 seaplane fighter with its pilot the group’s leading light Petty Officer Shinkichi Oshima safe after bailing out. Two Petes made forced landings at sea. Lieutenants Walter Dinn and Ronald Hilken failed to return. An escort mission on 20 January resulted in Capt. William Shaw claiming two Zeros not verified by Japanese records. Zeros of Air Group 204 claimed one P-38 destroyed and two B-17s damaged. 1Lt. Ernest Morris of the 68th FS was flying the P-38G that fell flaming into the sea. An interception over Guadalcanal on the 25th brought Lightning pilots claims for two Zeros destroyed without loss. Grumman Wildcats made additional claims. The Japanese suffered losses on this occasion but ascribe most of their losses to weather on the return flight. Japanese army light bombers escorted by Type 1 model I fighters attacked Guadalcanal two days after the Navy attack. Six intercepting P-38s, joining F4Fs and P-40s, started with an altitude advantage but were soon involved in dog fights below 20,000 feet. Capt. John Mitchell was credited with two victories and 1Lt. Ray Bezner with a one. Capt. Shaw’s Lightning was seen to blow up possibly from hits on a drop tank that failed to release. 2Lt. Morris McDaniel was missing after the combat. In the early morning hours of the 29th Capt. Mitchell tried his hand at night fighting. He caught a Japanese army light bomber during morning twilight and shot it down in flames witnessed by hundreds of ground troops. Based on claimed victories the P-38s had established a favorable victory to loss ratio to this point.

February 1943 is notable for fighter escorted heavy bomber (Navy PB4Ys and Army B-24s) raids on Bougainville and the Shortland area. P-38s provided escort cover along with P-40s and Marine F4U Corsairs. Corsairs could also reach Kahili from Guadalcanal. Raids on the 13th and particularly the 14th of February were later sensationalized as the St. Valentine Day Massacre. In addition to losses by bombers and other fighters four P-38s were lost each day while claiming three victories. This was not just a setback for the units involved. The South Pacific Command directed an end to daylight raids on southern Bougainville and surrounding areas. The hiatus in raids lasted nearly five months. This gave the Japanese respite to use the area as a transit point to strengthen their central Solomons defenses prior to the Allied invasion in June.

Yamamoto and Zero Rabaul

There were no P-38 claims or losses in March 1943. The P-38s placed a glow on their reputation in April. During a Japanese raid on Guadalcanal on 7 April 1943 four P-38s claimed eleven Zeros. Overall in that raid the defenses, intercepting fighters and AA, claimed more than twice the number of Japanese planes lost. Interestingly Admiral Nimitz monthly summary of events postulated this more than 2:1 over claiming almost exactly. On 18 April in a famous mission exploiting signals intelligence the P-38s downed a bomber carrying Admiral Yamamoto Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet and known as master mind of the Pearl Harbor attack. P-38 pilots claimed three bombers shot down (only two were involved) and three Zeros (none were lost). This mission’s supposed 6:1 victory to loss ratio along with the notoriety of its victim is the center piece of the Lightning’s reputation in the South Pacific in 1943. One P-38 was shot down and one returned badly damaged and was a write off. Each side lost two aircraft with P-38’s overclaiming by 2.5:1. These examples of overclaiming are far from the most egregious. By the end of 1943 P-38s had a positive reputation in the South Pacific. However, in terms of victory to loss ratio (3.2:1) they fell below all other fighters in the Command except the P-39. Considering verified examples of overclaiming it seems likely the P-38s lost about as many of their number in air combat as enemy aircraft they destroyed.

Southwest Pacific, November 1942 – February 1943

General Harmon in the South Pacific was generally pleased with the performance of P-38’s in early missions in his area. General George Kenney the advocate of bringing Lightnings to the SWPA was ecstatic with the first missions of the P-38 in his theater. After two missions in late December 1942 he wrote a letter directly to General Arnold Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces stating everyone in the SWPA was impressed with his air force’s performance: “Our air show has been an eye-opener to everyone.” He attached reports from some of the victorious pilots. Among them was 2Lt. Richard Bong America’s future ace of aces. Kenney’s forward echelon commander General Whitehead proclaimed, “We have the Jap air force whipped.”

The first SWPA P-38 victory against a Japanese fighter was unusual. P-38s of the 39th FS attacked Lae on 25 November 1942. Some Lightnings were armed with bombs. Others were escorts. Capt. Robert Faurot back from his recent duty on Guadalcanal missed Lae’s runway with his bomb. According to American accounts his bomb hit offshore where its waterspout caused a Japanese Zero that was taking off to crash.

Newly arrived P-38F 39th FS Australia 1942

Japanese raids on New Guinea targets and associated air combat were subdued for a long period from September to November due to Japanese commitments in the Solomons. That changed in mid-November when Japanese ground troops that had retreated to the vicinity of Buna on New Guinea’s north coast were confronted by an Allied ground offensive. The Japanese naval planes began to provide support against Allied ground forces and their supporting supply operations. They were joined by Japanese army fighters late in December. Several air combats took place in November and early December. P-39 and P-40 pilots made air combat claims with little action for the Lightning pilots. The only P-38 air combat claim was Faurot’s bomb kill. Kenney’s “eye-opener” letter referenced a combat between P-40E’s and Japanese army Type 1 fighters which occurred on 26 December. Fifteen Japanese fighters fought twelve P-40s of the 9th FS and four RAAF Hudsons and a Wirraway. Kenney mentioned the six Japanese fighters credited to the P-40s as well as one each credited to the Hudsons, the Wirraway and AA fire, total nine. One P-40 and one Hudson were shot down, others were damaged, and one P-40 force landed. The Japanese lost two fighters one of which was seen by ground troops to fall to the Wirraway. Results from overclaiming were not questioned but were endorsed in Kenney’s high level report.

The first big combat involving the Lightning in the SWPA occurred the day after P-40s of the 9th FS claimed six Japanese fighters when at most only one claim was valid. The Japanese mounted a joint army-navy mission to support their ground troops in the Buna area. Twelve Air Group 582 Zeros and twelve dive bombers were the navy contingent. The army’s 11th Hikosentai (Flying Regiment, FR) provided thirty-one Type 1 model I fighters. Over fifty U.S. fighters scrambled in response to radar warning. Only a dozen Lightnings and a dozen P-40s made contact. The 39th FS summary of the combat reads as follows:

At 1210, Capt. Lynch and his red flight consisting of Lts. Bong, Sparks and Mangas were warned of “Bandits” in the near vicinity. When locating the enemy planes, 20 to 30 Zekes and Oscars, with 7 or 8 Val-Dive Bombers. Captain Lynch led his flight of only 4 planes into attack the enemy of approximately 35 airplanes. During the combat the flight claimed seven victories. Capt. Lynch 2 Oscars, Lt. Bong 1 Zeke and 1 Val, Lt. Mangas 1 Oscar, and Lt. Sparks 1 Zeke and 1 Oscar.

During all this…combat White flight led by Lt. Eason were on their way, and got there in time to add more Victories to our squadron’s record… Lt. Eason bagged 2 Zero’s, Lr. Andrews 1 Zeke, Lt. Flood and Widman no victories…While at 20,000 feet the Yellow flight was preparing to attack the enemy below, and was dived on by two flights of Zekes, the first of 4 and the second of 6. In the ensuing combat Lt. Gallup claimed 1 Zeke certain, Lt. Bills 1 Zeke certain, Lt. Planck 1 Zero certain, and Lt. Denton 1 Zeke possible.

39thFS Ace Thomas Lynch

Eleven Lightnings returned to Port Moresby. 2Lt. Carl Planck took his damaged P-38 No. 36 to nearby Dobodura where it nosed over on landing. The P-40s claimed two Zeros as probable kills. Their pilots reported they were attacked by Lightings with a couple being hit. P-38 pilot reports verified that they had chased P-40s by mistake without admitting they damaged any. Most pilots of the 39th FS initiated their attacks with altitude advantage claiming thirteen victories, eleven fighters and two dive bombers. On the Japanese side one Type 1 fighter was lost with its pilot killed, another crash landed a write off. The navy also lost one fighter with second crash landed. A dive bomber returned badly damaged with two wounded crewmen. The Japanese suffered two outright losses, possibly three others were write offs.

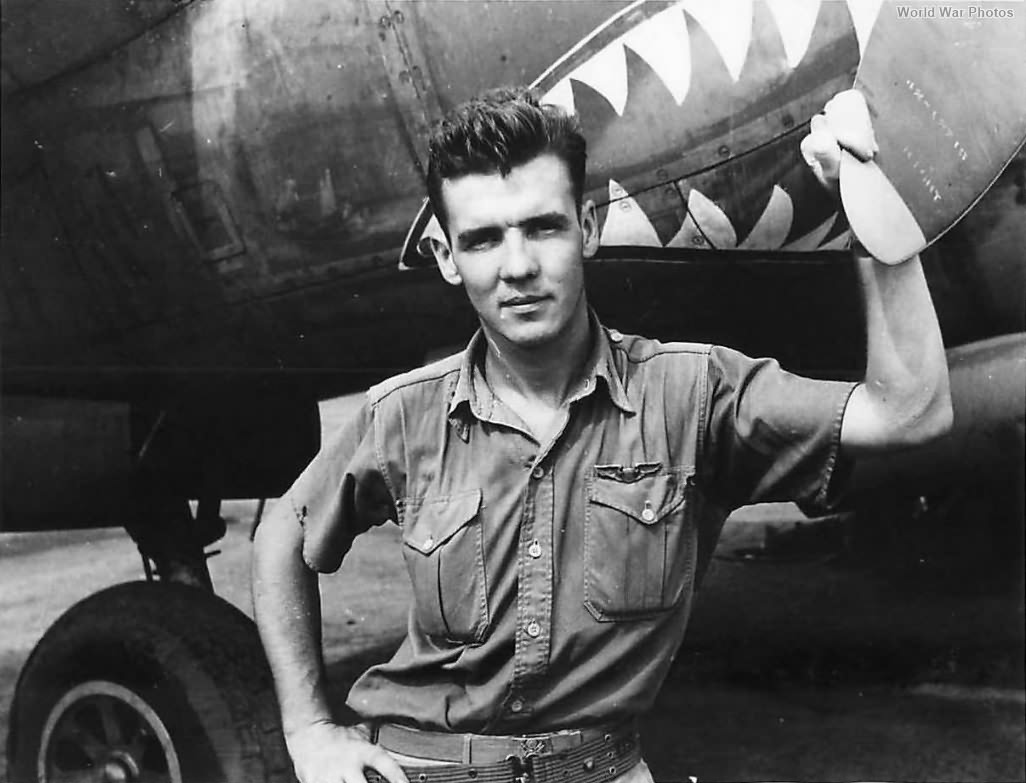

Richard Bong in his P-38

The second combat that burnished the P-38’s reputation, took place on 31 December 1942 the day before Kenney wrote to General Arnold. Twelve P-38’s of the 39th FS including three experienced Lightning pilots from the 9th FS escorted B-25 and B-26 bombers and six A-20 strafers to attack Lae airdrome. Eight Type 1 fighters intercepted. After one P-38 turned back with supercharger trouble eleven P-38’s in three flights engaged the Japanese fighters. Per the 39th FS report:

Red flight at 10,000 feet dived on 5 enemy Zekes at 5,000 feet. Captain Lynch getting 2 certain, Lt. Bong 1 Zeke probable, Lt. Lane 1 certain, and Lt. Sparks 2 certain. White flight as follows: Lt. Eason 3 certains, 1 damaged, Lt. Hyland 1 certain, and Lt. Thompson and Flood claim no Victories. Blue flight also have a victory to add to the grand total. Lt. Bills 1 Zeke certain. Planck and McGuire claim no Victories. All planes returned repairable at 1330. All pilots report the enemy they engaged today were much better quality than the last combat, both planes and pilots. Total for today was 10 certain and 2 probable.

Lts. Ken Sparks and Carl Planck returned to Moresby in damaged fighters. Sparks had a wing tip ripped off and an aileron damaged in a collision with a Jpanese fighter. Over claiming was hardly unknown for the Japanese. They claimed four P-38s including two uncertain and two bombers damaged. None were lost. The Lightning pilots claimed more victories than the number of Japanese fighters engaged. 1Lt. Hironojo Shisimoto was shot down but survived the bailout. 1Lt. Tomoari Hasegawa flew the Type 1 Hayabusa that collided with Sparks. He managed to fly part way to Rabaul before landing his damaged aircraft at Gasmata on the southern coast of New Britain.

Spark's damaged P-38

Beginning on 6 January 1943 for nearly a week the Fifth Air Force bombers and fighters flew numerous missions against a Japanese convoy running reinforcements to Lae. The SWPA Lightnings suffered their first combat loss during this operation. After this operation enthusiasm for the P-38 as a dive bomber faded rapidly. There were many air battles and overclaiming on both sides. Both Japanese army and navy fighters were involved as were several types of Allied aircraft. It is often difficult to identify specific losses with particular combats since the numerous actions sometimes overlap. Late on the sixth, however, a combat occurred in which the combatants can be identified. Sixteen 39th FS P-38s, eight with bombs (one turned back) and eight as escorts, were guided to the convoy by a B-17 providing navigational aid. Some of the P-38 bombers joined their escorts in confronting the Japanese convoy cover which consisted of Type 1 fighters most correctly identified in the P-38 report. The Oscars of the 3rd Chutai 11th FR arrived on the scene just as the dive bombers completed their unsuccessful bombing attacks. By 39th FS count there were fourteen. Claims ran to nine destroyed (two identified as Zekes), three probably destroyed and two damaged equaling fourteen. In addition the B-17 reported being attacked by six to eight Zekes and Oscars and gunners claimed one of each type destroyed. No Zeros (Zekes) were present in this combat. Captain Curran Jones claimed two victories. Seven other pilots claimed single victories. All the P-38s returned to base. The Japanese did not claim any certain kills but two of their number failed to return. A month later in the vicinity of Salamaua thirteen P-38s flying at 18,000 feet engaged in a diving attack on ten to twelve Oscars and claimed one destroyed. Later P-38s of the recently reequipped 9th FS also encountered Oscars in the same area and claimed their first P-38 victory. Neither side suffered any loss in these encounters.

In the South Pacific Harmon was fine with what his P-38s accomplished in their early missions. In contrast his pilots had some rather caustic critiques regarding the aircraft and how it was used. In the SWPA Kenney was ecstatic. His pilots were being credited with kills at a high rate while suffering modest loss and damage. His pilots were pleased with their new mount. This leaves one voice unheard. What did the Japanese think of their new opponent?

After the combats of 27 and 31 December pilots of the 11th FR wrote the following assessment of the P-38:

Performance of the P-38 (below 5,000 meters). 1. Maximum level speed. Appears to be 20 to 30 km/h faster than Type 1 Fighter. At extremely low altitude speed appears to be roughly equal. 2. Climb rate. Slightly superior to Type 1 Fighter. Speed of climb is particularly fast. Initial acceleration into climb, however, is slow. 3. Dive. Slow to accelerate at start of dive and easily pursued by Type 1 Fighter, but rate of acceleration once in the dive is great and unable to pursue due to risk of structural failure (indicated speed 550-600 km/h). 4. Turning radius. Horizontal turn. Approximately same as Type 2 Two-seat Fighter. Radius of vertical loop very large.

The Japanese army pilots were not overly impressed by the P-38 from these early contacts. They also recognized if used in a way that took advantage of its strong points the P-38 could be a formidable opponent.

Of course an aircraft cannot always be used in a way that emphasizes its strong points. On 2 August 1943 a big combat between American bombers and fighters and Japanese fighters took place over the Huon Peninsula. After the main combat, five P-38s sighted a Japanese Type 1 model I fighter headed for home base over the straits between New Guinea and New Britain. The Lightning pilots reported:

For fifteen minutes the five of us made pass after pass at this fighter, although we didn’t get it. When he got the opportunity the pilot would straighten up momentarily up-coast, sucking us with him…This pilot was pretty good. He kept close to the water and would turn gradually until we were on him, then he would slip down to the water in a tight turn…I made at least six passes on him until the leader ordered us home.

Tragically in January 1945 America’s second leading ace Thomas McGuire lost his life flying a P-38L when he ignored his own tactical rules and engaged a Type 1 fighter in a low altitude turning combat.

For other examples of the P-38 in combat with Japanese fighters check out South Pacific Air War. Chapter 19 is particularly interesting regarding P-38 “superiority.”