The story of captured Allied aircraft in Japanese hands offers a fascinating glimpse into the improvisation and ingenuity necessitated by wartime constraints. Among these tales, the saga of the Hankow Warhawks—a squadron of P-40Ks abandoned on a Yangtze River sandbank and subsequently seized by Japanese forces—stands out for its blend of adventure, technological exploitation, and symbolic significance. This episode, set against the backdrop of shifting air combat dynamics in China during 1943, highlights how Japan’s tactical and strategic decisions were influenced not only by the acquisition of Allied equipment but also by the lessons learned from their use. From the dramatic recovery of these aircraft to their mysterious fate in Hankow, this article underscores the broader theme of how captured aircraft shaped the intelligence, tactics, and propaganda efforts of the war in the Pacific.

One place to begin the story of captured Allied aircraft in Japanese hands might be before the war in the Pacific began. Indeed the restriction on American aircraft exports to Japan is a key part of the diplomatic trail that led to the Japanese ultimatum, their “declaration of war”, of December 1941.

Export Controls

In July 1938 one year after the Sino-Japanese Incident began the U.S. State Department notified aircraft manufacturers that the U.S. government “strongly opposed” the sale of airplanes or related materials to nations using airplanes to attack civilian populations (the Moral Embargo). Among the related materials were machine tools and aviation gasoline. The U.S. was Japan’s main supplier of petroleum including aviation gasoline and Japan was clearly the target of the embargo. Incidentally, one of the reasons the China-Japan war was called an “incident” was to avoid Neutrality Act restrictions on supplying military goods. Trade in such articles mainly to China helped American industry during the Depression. In July 1939 the U.S. gave Japan the required six months’ notice of withdrawal from the commercial treaty of 1911 denying Japan “most favored nation” status.

While the Moral Embargo was in force the Seversky Aviation Company sold Japan twenty two-seat 2PA-L fighters. This enraged the Roosevelt administration. The Seversky P-35 a single-seat derivative of the exported fighter won a design competition with the Curtiss P-36 in 1937. That Seversky never received the quantity of production orders anticipated may have been affected by its flaunting of government policy. Seversky lost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Alexander de Seversky was forced out of the company. The company was reorganized as Republic Aviation and eventually produced the excellent P-47 Thunderbolt fighter.

All the above is to say Japan had little access to American aviation technology in the years before World War Two. Likewise Great Britain which sold airplanes to China during the “Incident” was focused on building its own defenses and did not export its best aircraft in the immediate pre-war period. During this period key advances were taking place in aviation technology. This was not a one-way street. The Extra Super Duralumin (E.S.D.) in the wing spar and other components of the Mitsubishi Zero carrier fighter was superior to any similar alloy available to the Allies throughout the war in terms of weight and strength.

The Value of Captured Aircraft

The Allies both in the western theaters and in the Pacific were assiduous in inspecting captured aircraft. For the most part these were wrecked aircraft that had crashed, or unserviceable aircraft left behind on captured airfields. Inspection of crashed aircraft could reveal various types of useful information. The dimensions and physical characteristics of the aircraft, its engine(s), protective features and other characteristics were recorded. Upgrades of armament or other equipment were noted. Data plates could reveal its place of production, service life and with enough examples yield an approximate rate of production. As useful as inspection of wrecked aircraft was, the real prize was an aircraft in fully operational condition or one capable of being restored to such a condition. A flyable aircraft could yield performance data that indicated strong and weak points of its performance. This allowed for comparison with friendly types and potentially might yield data that informed the optimum tactics to use in opposing an enemy aircraft, information of great value.

Recovery of crashed Zero(1)

The value of flyable captured aircraft has occasionally been overstated. This is true in the Pacific War. One of the best examples is the crashed Zero 21 recovered in Alaska, rebuilt and test flown at San Diego. This is sometimes represented as a great intelligence coup. By the time the aircraft was test flown in October 1942 most of the flight characteristics of the Zero were well known from combat experience. Little new was learned from mock combats with American fighters. Performance data derived from test results was inaccurate due to certain airframe anomalies and incorrect boost settings used for the test. Due to lack of documentation incorrect boost (supposed full power rating limited to 2,600 r.p.m vice Japanese specifications of 2,750) was also used in establishing performance curves for the captured rebuilt Zero 32 tested in Australia. Thus inaccurate information was disseminated.

Early War Bonanza

With the Allies ousted from the Philippines, Malaya, the Netherland East Indies and southern Burma the Japanese Army came into possession of large numbers of captured Allied aircraft. Malaya and British operations in the N.E.I yielded Hawker Hurricanes, Brewster Buffaloes, Bristol Blenheims, Lockheed Hudsons and others. The Philippines and the N.E.I. brought the Japanese American aircraft such as the Boeing B-17 (models D and E), Curtis P-40s, Republic P-35As, and a variety of other aircraft which the Japanese characterized as forty-five large aircraft and forty each medium and small aircraft.

The Japanese recognized that many of the aircraft captured were second-class weapons. The P-40 gained some attention for its high quality “bullet-proof equipment”, i.e., armor and self-sealing fuel tanks. The B-17 impressed the Japanese for the same reason. The B-17 along with another advanced aircraft, the Douglas DC-5, was minutely tested by technical experts from Japan. Otherwise, at the time the B-17 had not made much of an impression on the Japanese as far as its combat efficiency. However, later it was to become particularly troublesome resulting in the Japanese Army setting up a task force to study countermeasures to the B-17. Captured Flying Fortresses apparently played a key part in that effort.

The Japanese Southern Army (high command in the southern theater) decided on April 1, 1942, to send some of the captured aircraft back to Japan in order to contribute to research, development and production of aircraft in Japan. In addition to aircraft various items of aircraft equipment were also sent to Japan. These included life preservers, pyrotechnics, and ammunition. Japanese efforts to obtain “radio locators” (radar) in Malaya and the N.E.I. were unsuccessful. The Allies had been thorough in destroying all examples that had been abandoned there. However, the Japanese captured an SCR-268 gun laying radar (also useful for early warning) in the Philippines.

Certain Allied equipment was not only evaluated but put into use by Japanese forces. Particularly prized was the Browning .50 caliber (12.7mm) machine gun which equipped several Japanese anti-aircraft battalions. It was deemed superior to Japanese 13.2mm and 20mm guns used for the same purpose. Captured U.S. M-3 light tanks (medium tanks by Japanese standards) were shown in Japanese press photos displaying Japanese insignia having equipped a Japanese armor unit in the Philippines. When the 64th Hikosentai (Flying Regiment or FR) transferred from Malaya to Thailand it had a couple Hawker Hurricanes on strength. The 50th FR started the war in action over the Philippines. For a short time in early 1943 the 50th fielded a few P-40Es captured in Java for air defense at Rangoon, best known because a Japanese bomber was shot by one down in a friendly fire incident. Captured P-40s and Brewster Buffaloes appeared in Japanese propaganda films. Other equipment stymied the Japanese. They did not even know what to call a bulldozer – an item that proved important in Allied airfield development and in other engineering efforts during the war.

The rapid Japanese conquests in the early months of the war had not confronted them with any cases that suggested that radical innovation in aeronautical technology was necessary. Likewise their traditional tactics were deemed to have served them well. Thus it was not immediately apparent that new technologies or changes in tactics were needed. Recognition of the need for change unfolded gradually. In certain areas such as radar and self-sealing fuel tanks the Japanese lagged the Allies for the entire war.

Captured Aircraft in Japan

One of the first uses of captured aircraft involved the B-17. Unlike Japanese impressions from confrontations early in the war, in later campaigns the B-17 proved to be both a good bombing platform and to have excellent defensive characteristics because of its performance and defensive armament. As noted above the Japanese Army conducted a study regarding B-17 counter measures. The Japanese Navy convened a conference on the same subject at Yokosuka in November 1942. Upon recovery from wounds received over Guadalcanal Navy Zero ace Saburo Sakai flew in a B-17. The aircraft had been captured at Bandoeng, Java, in March 1942. Sakai “got a kick out of flying the bomber, which impressed us with its controllability and, above all, the precision workmanship of its equipment. No large Japanese airplane I had ever seen was in its class.” However, it was the B-17’s ability to survive fighter attacks and inflict losses on attacking fighters that caused the Japanese to convene study groups on how to deal with the Flying Fortress.

Based on combat experience a Navy air group in the New Guinea area had concluded that attacks from head on (between 11 and 1 o’clock positions) were most likely to inflict damage without ruinous losses to the attackers. Head on attacks involved a fast closure rate and limited firing time but avoided much of the B-17’s defensive armament with, however, the added risk of a head on collision. This approach was tested by the Japanese Army. A Japanese news reel showed Army fighters in line astern formation passing a captured B-17D, pulling ahead and then turning in for head on attacks. When the Army’s 11th FR deployed to Rabaul in December 1942 initial confrontations between its Type 1 model I (Oscar) fighters and B-17s were unsuccessful. On 5 January 1943 American reports confirm that the head on tactic like the one in the Japanese news reel was used. Two waves of fourteen B-17s and B-24s attacking Rabaul were intercepted by Army Type 1 fighters in conjunction with a few Navy Zeros. In the first wave one damaged B-17 ditched off New Guinea and a second damaged bomber landed at an advanced base but was a write off. In the second wave one B-17 was shot down and a badly damaged B-24 that landed away from its home base was later destroyed in an air raid. Two Japanese fighters were lost. This was a particularly successful interception. It apparently confirmed the Japanese in adopting the new tactical approach. After this U.S. heavy bombers attacked Rabaul only at night for several months until fighter escort could be provided.

Ki-43_II_Ko_25_Sentai_China_1943

The Japanese Navy borrowed a B-17 from the Army to conduct tests of an experimental night fighter technique. In the new tactic a Type 2 land reconnaissance plane (Irving) armed with 20mm cannon fixed at an angle stalked the B-17 from above or below the bomber’s flight path. The tactic was introduced in combat at Rabaul in May 1943 with immediate success.

Captured aircraft also played a role in ceremonial and public relations events. At the Autumn Festival of the Yasakuni Shrine in October 1942 the Nippon Times included a photograph of General O. Yamada chairman of the festival. The General is seen passing a display of a P-40E in early war U.S. insignia and a tropicalized Hurricane II.

This Japanese press account appeared on December 2, 1942:

Enemy warplanes seized by the Japanese armed forces will roar over the spacious flats and embankment of the Tamagawa River for the benefit of Tokyo’s air minded citizens on December 6 as a prelude to the commemoration of the first anniversary of the outbreak of the War of Greater East Asia on December 8, states Domei.

In a varied aerial program, former Anglo-American battle planes, including Curtiss P-40, Hawker-Hurricane and Brewster Buffalo aircraft, manned by Japanese pilots are slated to engage in stunt flying while Lockheed Hudson and Douglas A-20A aircraft will sweep low in exhibition flight.

One of the features of the day’s event will be a mock combat between a swift Japanese “Hayabusa” fighter and a Boeing bomber in which the pilots are expected to give the crowd a near realistic as possible demonstration of an actual aerial combat.

As planes zoom overhead simulating an attack, an Army Engineer Corps is slated to blast in the Tamagawa River so as to enhance the atmosphere of actual warfare.

The Hankow Warhawks

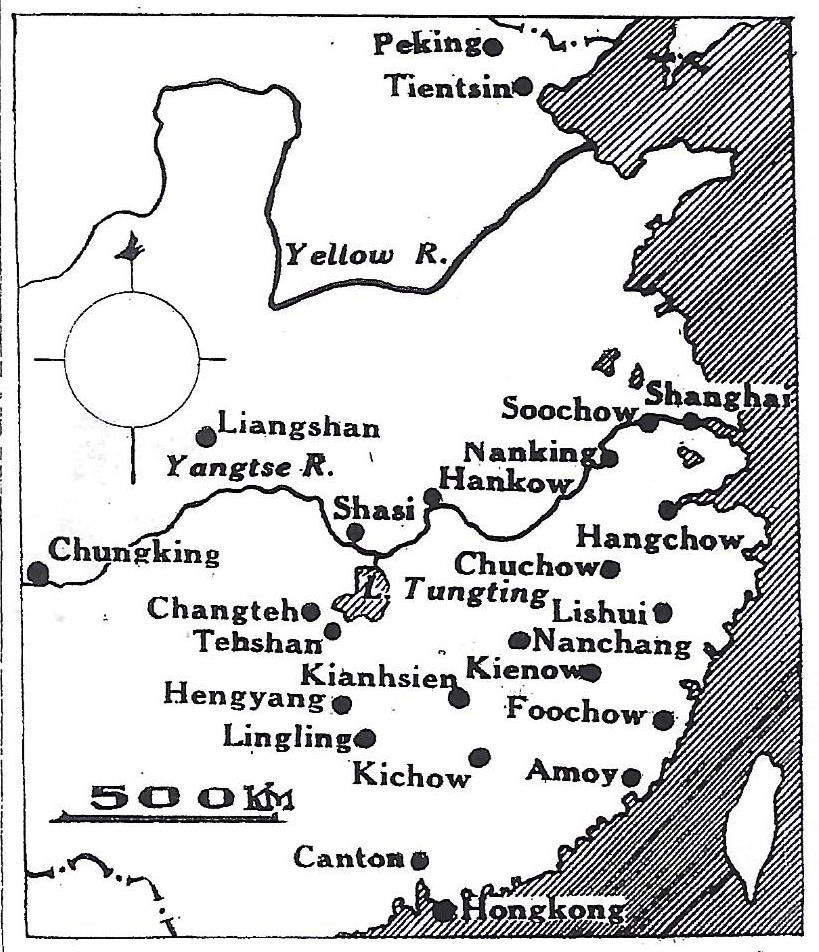

A fascinating incident illustrates the impact that captured aircraft may have. It took place in China in 1943. The story is firmly based in fact aided by some informed conjecture. The air war in China involved three parties: The Japanese 3rd Flying Division (FD), The U.S. Fourteenth Air Force, and the Chinese Air Force. The story begins on 31 May 1943 a day on which all three forces were active. Nine B-24Ds of the 374th and 425th Bomb Squadrons (BS) were detailed to bomb Kingmen airfield. Diverted by weather they dropped bombs near Ichang. Near Kingmen the B-24 escort of nine P-40s led by Lt. Col. John Alison (two American and seven Chinese pilots) effectively protected the bombers when they engaged an estimated twenty Japanese fighters. The B-24s later engaged additional Japanese fighters after their escorts left. The American fighter pilots claimed one confirmed and two probable victories. Chinese fighter pilots claimed two certain and one probable victory. Bomber gunners claimed twenty kills and additional probables. One Chinese P-40 was lost. One Type 1 fighter from 1st Chutai, 33rd FR was lost. Alison barely made it to a Chinese airfield in a badly shot up P-40 landing on two flat tires, his last air combat in China. Chinese A-29 attack aircraft escorted by P-66 fighters attacked the Yangtze River ferry crossing between Ichang and Itu. Late in the afternoon a dozen P-40Ks of the 76th Fighter Squadron (FS) led by Squadron CO Maj. Grant Mahony took off from Lingling to strafe targets in the Ichang area. This did not go well. Adverse weather intervened. The strafing flight flew below a cloud deck and the cover flight flew above. The strafers could not find their primary target, strafed an alternative target, two made emergency landings away from Lingling due to fuel shortage. Five P-40s from the top cover became completely lost and ran low on fuel. They landed on a sand bank in the middle of the Yangtze River.

P-40K and pilots of 75th FS 1943

The harrowing adventures of the pilots of the Warhawks that landed on the sand bank is a story itself. Captains Robert Mayer, Jewell Mathews and Lts. Sam Berman, George Dorman, and Lawrence Durrell made it to Hengyang after more than two weeks. They met Chinese Nationalist guerillas who initially “arrested” them not knowing their identity as Americans. A guerilla who was a former Chinese civil servant and knew some English, villagers, a missionary, and others provided help. For most of the time it took, much on foot, to get back their whereabouts were unknown to their squadron. Their journey from sand bar to Hengyang was filled with danger and adventure. Guerillas fought a couple delaying actions with Japanese troops to aid in their escape. Reportedly the Japanese radio announced they had been captured. Wearing Chinese clothes with shaved heads they eventually returned to U.S. control. Our story, however, focuses on the P-40K Warhawks on the sand bar.

Mid-year 1943 saw a change in the aerial combatants in China. An influx of fifty-plus P-40Ks and P-40Ms largely replaced the long service P-40Bs and P-40Es in the 16th, 74th,75th, and 76th FS by the end of May. The 449th FS equipped with the P-38G arrived in July. On the Japanese side the 25th FR left for Japan during June and returned re-equipped with Type 1 model II fighters. The 33rd FR re-equipped more gradually but was fully equipped with the model II by July. Newcomer the 85th FR arrived from Manchuria in July equipped with the Type 2 fighter (Ki 44-II). American fighters were concentrated at Kunming and other bases in Yunnan with forward bases in central China. The Japanese fighters were concentrated at Wuchang and Hankow with detachments at Canton and Hanoi. By the end of July wrecks of crashed Type 1 Model II fighters and a Type 2 fighter were inspected. This supplemented by POW interrogation allowed Fourteenth Air Force intelligence to determine the Japanese had fielded a new fighter (codenamed Tojo) as well as an upgraded version of the familiar Oscar. Official Japanese designations and American codenames did not keep American pilots from using “Zero” as the generic name for any single-engine Japanese fighter they encountered.

Ki-44_85_Sentai_China_1943

The day after the five P-40Ks made force landings on the sand bank they were spotted by a Type 98 direct cooperation plane (Ki 36, Ida) which landed on the sand bank. Its crew found the aircraft in good condition. The location was near Sha-shi a district on the northern shore of the Yangtze River in Hubei Province. Arrival of this news at Hankow resulted in a mission to recover the aircraft. Troops of the 57th Airfield Battalion under Capt. Ryozo Hoike were charged with the recovery. The aircraft were loaded aboard Daihatsu large type motorized landing craft and shipped down river to Hankow.

Tachikawa Type 98 direct cooperation aircraft

Exactly what happened at Hankow is unclear. As will be seen below there is no doubt the aircraft were put into flying condition. Whether the Japanese serviced them with captured 100 octane aviation gasoline or something less is unknown but likely 100 octane was used. One Japanese source indicates at least one of the aircraft was used for combat training by the 25th FR. Other evidence is that all five were used. A 15 September 1943 Fourteenth Air Force intelligence summary states: “The Chinese Air Force reports that five of ten Jap fighters over WUCHOW on September 7th appeared to be P-40s and carried U.S. symbols.” In any event the report suggests the P-40s were used for something more than just basic performance testing. It appears the Japanese used the P-40s in a way that allowed them to develop new tactics for use by the model II Oscar and Tojo against late model P-40s. This may have involved successive chutai (flights) engaged in mock combat with the captured aircraft.

On 15 September the same day as the intelligence summary mentioned above a half dozen B-24s escorted by fourteen P-40s bombed cotton mills at Wuchang. The P-40s did a good job keeping the “Zeros” away from the bombers claiming one destroyed but losing one of their own number. Interestingly, “One flight of Zeros flew high above the formation without attacking.”

When the Japanese fighters were not escorting bombers, new tactics could be used to good advantage. On 20 August fourteen P-40s of the 74th FS led by group commander Col. Bruce Holloway encountered a fighter sweep composed of fighters from the 25th, 33rd and 85th FRs; the Americans estimated their number as twenty-plus. The Japanese fighters were operating at 30,000 feet and above. They employed dive and zoom tactics. The Americans claimed two Japanese fighters destroyed and lost two of their own number. The Japanese claimed two certain and three uncertain victories. They lost one Type 1 fighter and pilot from the 33rd FR.

On 5 October nine P-40s and a P-38 clashed with Japanese fighters including “new type Zeros” at 27,000 feet. There was no U.S. loss, and one confirmed victory was claimed with a couple probables. The 85th FR lost one Type 2 fighter with its pilot killed. Soon thereafter a mixed P-38 and P-40 formation encountered Japanese fighters at high altitude. The P-40s failed to make contact and the P-38 combat which took place at 34,000 feet was inconclusive. U.S. fighter pilots had already taken notice of improved performance and new tactics used by Japanese fighters and made their opinions known.

“Tactics used by Japs…showed definite improvement over previous tactics. By using their superior altitude they remained out of range of the P-40s, dropping down by twos and threes to make one or two passes then zooming to altitude as soon as their advantage was lost. Under such tactics the P-40 will not operate effectively against them.” (Lt. Col. Norval Bonawits, 74th FS, late August 1943). “New airplanes… are needed immediately to combat the new improved Japanese fighters which have both speed and altitude advantage over our P-40s.” (Maj. Edmund Gross, 75th FS, late August 1943). “Recent operations against the new type Zero have shown that the P-40 has little, if any, advantage in speed – (one of the few advantages we have had up to this time).” (Capt. William Crooks, 74th FS). “The Japanese have evidently changed their tactics in this area and no longer come in below 20,000 feet. Instead they come in above our P-40s and we are unable to get to their altitude. Our planes indicate only 120 miles per hour at 30,000 feet and will go no higher.” (Maj. Robert Liles, 16th FS, September 1943). A comment on the new Zero was “This ship is able to dive with the P-40 thus leaving us at their mercy.” (Maj. Robert Costello, 76th FS). “A P-40 must have several thousand feet altitude to be sure of out diving the new type Zero…They are able to dive with the P-40 to speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour. They have several thousand feet altitude advantage.” (Lt. Col. Samuel Knowles, 23rd FG headquarters, September 1943). These reports of new fighters and improved tactics came in from every P-40 squadron regardless of their location indicating new fighters and improved tactics were in use in every sector of the theater. Most of the new fighters were Type 1 model II fighters. Some comments (diving speed) obviously refer more specifically to the Type 2 fighters.

23rd Fighter Group CO Col. Bruce Holloway in his P-40K

During its 1943 summer offensive (23 July – 7 October) when the 3rd FD was temporarily reinforced by two Type 97 heavy bomber units, 103 Allied fighters and 21 bombers (including Chinese) were claimed shot down or destroyed on the ground. During this period Japanese fighters had a remarkable string of successes against B-24s ( The B-24 Liberator in Chinese Skies – Summer 1943 – RLDunn ). The Japanese lost 25 fighters, and 15 bombers shot down or failed to return. Whatever the actual victory to loss ratio, not only new model fighters but new tactics had a profound impact on American fighter pilots. No additional high altitude, fuel guzzling P-38s would be added to the American order of battle. However, by November P-51As, providing a measure of improvement over the P-40, were arriving and in 1944 the first high speed, high altitude P-51Bs joined in to make life harder for the Japanese fighter force.

To add conjecture to fact it seems possible that the Japanese in China conducted something like a later day Red Flag exercise. In any event they clearly changed tactics to the disadvantage of their adversary. The Warhawks captured on a sand bank of the Yangtze were almost certainly at the center of this change in tactics.