Numerous books and articles have been written about the air fighting that went on along with the ground combat and naval battles occasioned by the U.S. invasion of Guadalcanal and Tulagi beginning August 7, 1942. Little has been written about air operations over Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the months before the invasion. This article attempts to start to fill the void in the published historical record of that period.

Background

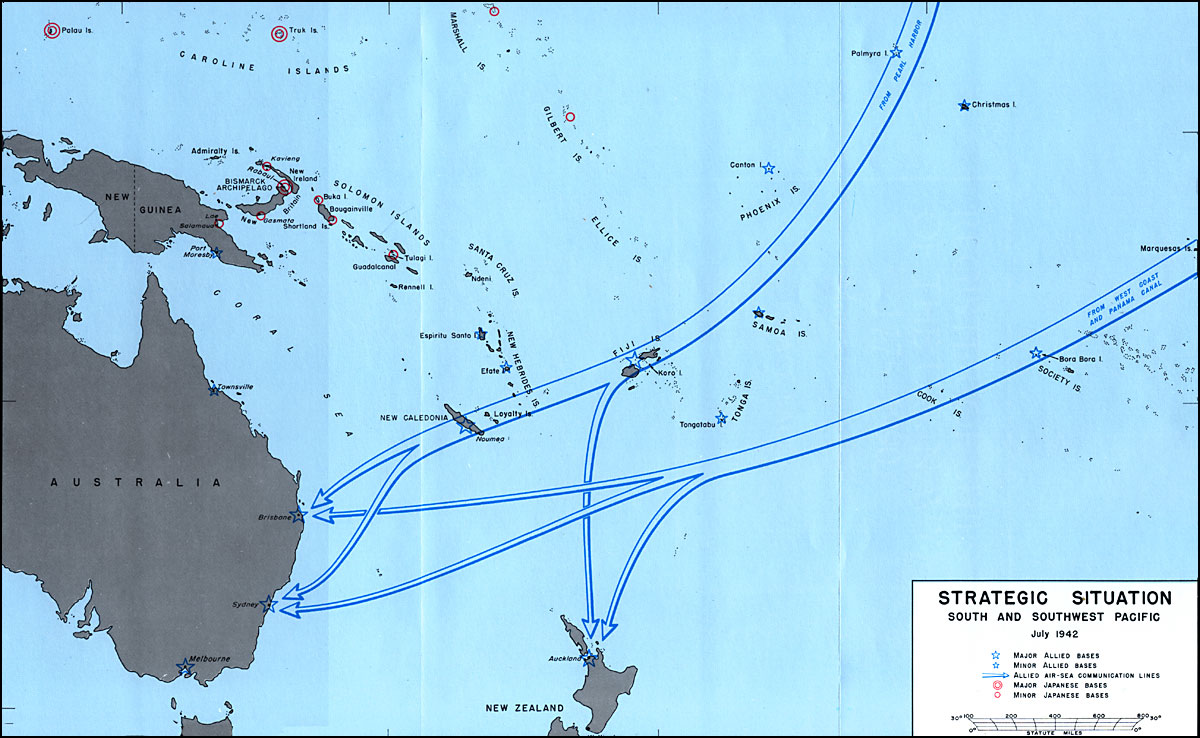

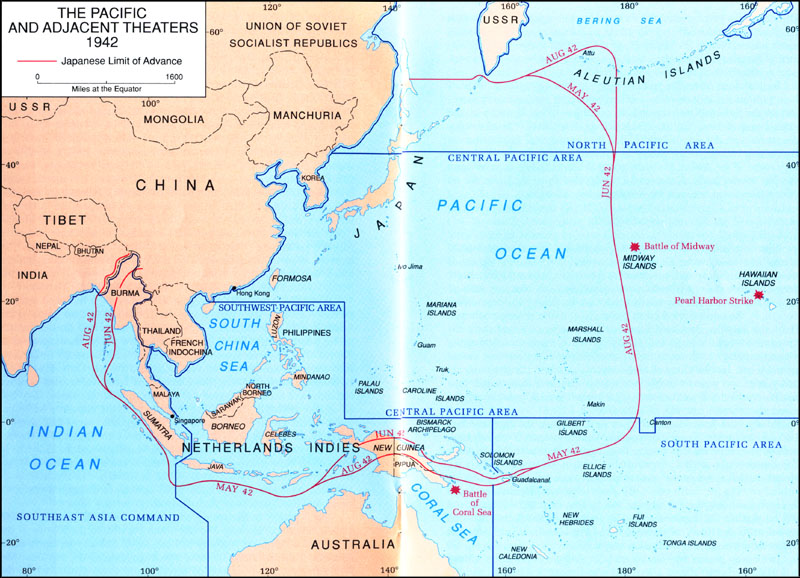

Initial Japanese offensive operations achieved notable success by March 1942. They were poised not only to succeed in conquering the “southern resource area” they coveted but were within sight of establishing a defensive perimeter to maintain their key positions. One potential fly in the ointment was Australia. Unless isolated it could become a jumping off point for future Allied offensives. This led Japanese planners to see the need to occupy Port Moresby on New Guinea’s southern coast. Beyond this they developed a plan to occupy New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa. The possession of air and naval bases on these islands would complicate and possibly completely disrupt lines of communication between Australia and the U.S. whether originating on the U.S. west coast, Hawaii or through the Panama Canal. Occupation of the seaplane base at Tulagi and developing an air base in the same area were important steps in their prospective Fifi-Samoa or FS operation.

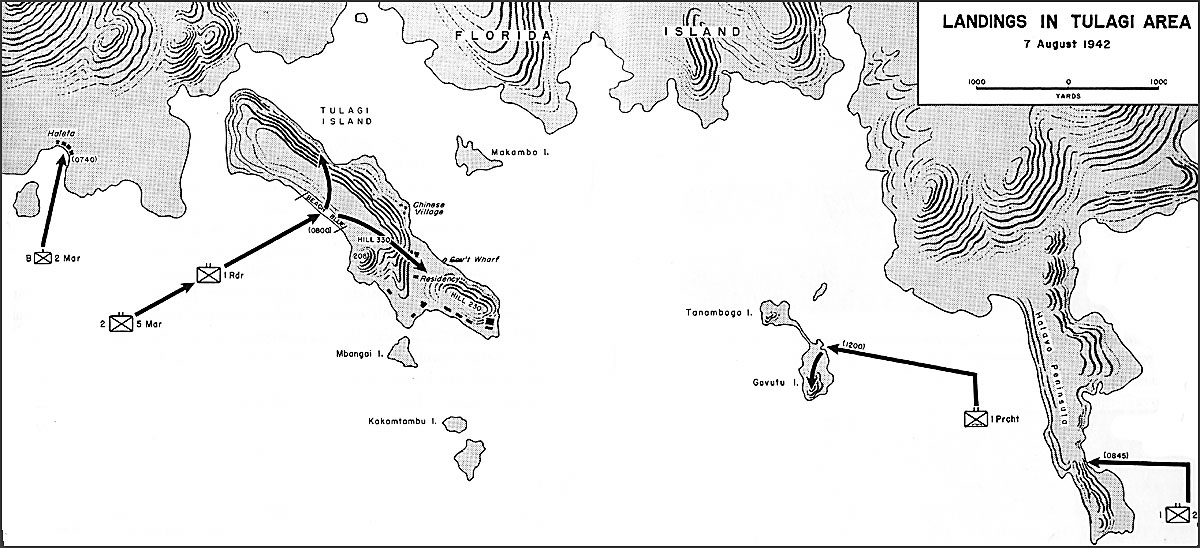

The Royal Australian Air Force (R.A.A.F.) operated a seaplane base on tiny Gavutu Island (connected by causeway to Tanambogo I.) in Tulagi harbor where typically four or fewer Catalinas were based. Tulagi was mentioned in Japanese Imperial General Headquarters planning as early as the beginning of February 1942. Tulagi became a target in Japanese plans in connection with their prospective seaborne invasion of Port Moresby as well in their longer term vision of Operation FS. Allied intelligence got its first hint of a Port Moresby operation at the end of March. Despite the fragmentary nature of most intercepted messages during April the target and the potential array of invasion forces became clearer. Substantial American naval forces were sent south from Hawaii to counter Japanese moves into the Coral Sea.

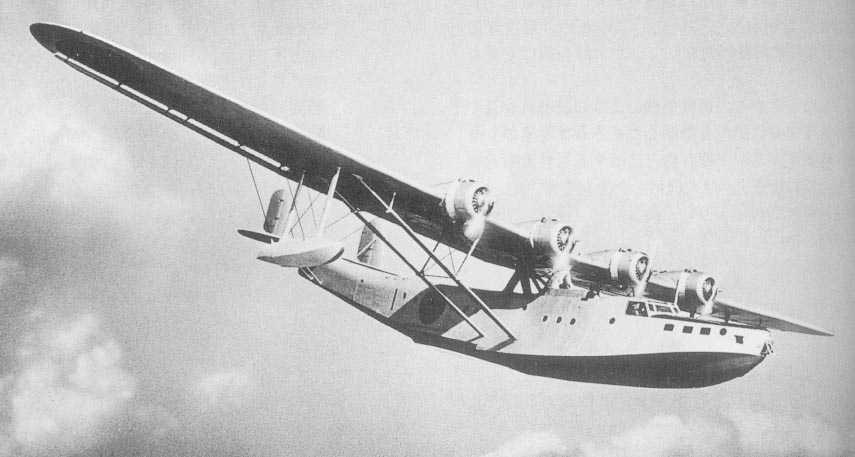

For local Japanese commanders, Tulagi had already caused concern. The small cadre of R.A.A.F. Catalinas was flying reconnaissance missions from the base and occasionally bombing Japanese shipping and bases in the northern Solomon Islands. The Japanese carried out three raids on the base in March. The first was by three Type 97 large flying boats (H6K2), identified as Serial 43s in the Allied identification system then in use, on the 17th. Minor damage was inflicted on a Catalina. Two days later a mixed force of flying boats and Type 96 land attack bombers (serial 37s) caused slight damage at the seaplane base and killed a few natives on Tulagi Island. Imperial General Headquarters communiques merely announced these raids among a list of targets hit with no details. In April there were four raids. On 9 April five flying boats wrecked the airmen’s quarters and damaged the store and kitchen. Power and radio communication were temporarily disrupted. On the 25th eight land attack bombers damaged some buildings but despite bombing from only about 4,000 feet dropped a portion of their bombs in the harbor. On the 29th bombs from three flying boats damaged two of three Catalinas (A24-23, seriously damaged was ultimately a write off). R.A.A.F. records indicate the attack occurred the following day; not the only date/time confusion between the accounts of the opposing sides.

Type 97 Large Flying Boat

An aspect of the Battle of the Coral Sea was the Japanese occupation of Tulagi and the Allied reaction. It has been covered in other studies and books to which the reader may refer if more detail than provided here is sought. A Japanese naval group (Shima Force) supported the larger Moresby invasion by its occupation of Tulagi. Plans called for it to sortie from Rabaul on 30 April. On the same day five Japanese flying boats advanced to Shortland to begin patrols from there where observation floatplanes also operated. Once Tulagi was captured the flying boats were to operate from that more advanced base. The Japanese sent ships to establish a temporary seaplane base at Rekata Bay, Santa Isabel Island. Part of the air group of Kiyokowa Maru an auxiliary seaplane carrier was left in the area when the damaged mother ship returned to Japan earlier. These aircraft supplemented those of Kamikawa Maru. Seaplane tenders reported to the Japanese 4th Fleet rather than the “base air force” 25th Air Flotilla.

Type 95 Reconnaisance Seaplane

Yokohama Air Group with twelve Type 97 large flying boats reported to the 25th Air Flotilla. Capt. Shigetoshi Miyazaki CO of the Yokahama Air Group established his headquarters on Tulagi a few days after the initial landing. With him came four hundred group personnel, two-thirds its total strength, and half its flying boats.

On May 2nd an R.A.A.F. Catalina sighted ships of Shima Force headed northeast from the Solomon Sea toward Tulagi. Due to weather conditions its attack failed to inflict any damage. After 0600 hours Japanese floatplanes began a series of strafing raids that lasted until 1700 hours. It was apparent to the R.A.A.F. officer in charge, F/O R.B. Peagam, 11 Squadron detachment, that his small force of Australian army troops and airmen numbering about fifty could not resist the approaching invasion force. Peagam received orders to evacuate. After demolition of facilities the Australians transferred to Florida Island. From Florida they obtained passage on a small trading vessel to Vila on Efate Island and ultimately to Australia. After dark the ships of the Japanese invasion force arrived at Tulagi harbor. About four hundred troops of No. 3 Kure Special Naval Landing Force occupied the islands the following morning. Late on the third news of the Tulagi landings reached commanders of American task forces who prepared for carrier strikes the next day. In the harbor were RAdm. Kiyohide Shima’s flagship 4,500-ton minelayer Okinoshima, two destroyers, and nine other vessels mainly auxiliary mine or patrol craft. Some of Kiyokawa Maru’s floatplanes flew from Shortland in the early morning darkness and were moored at Gavutu. An advance party from Yokohama Air Group occupied the former R.A.A.F base.

RAAF 11 Squadron Catalina

Aircraft carrier U.S.S. Yorktown launched a series of attacks against the assembled Japanese shipping beginning early on the fourth. Twenty-eight SBDs of VB-5 and VS-5 carried 1000-lb. bombs while a dozen TBDs of VT-5 armed with torpedoes executed the first strike. After inflicting some damage despite fogging of telescopic bombsights and faulty torpedoes, all forty aircraft returned safely to the carrier to be rearmed for a second strike. Twenty-seven SBDs and eleven TBDs were launched at mid-morning. Attacking around noon the bombers were opposed by Type 95 (E8N2) reconnaissance seaplanes. Two floatplanes were claimed by SBDs. One was shot down and one destroyed on the water. TBDs also encountered floatplanes when they attempted unsuccessfully to torpedo Okinoshima. However, one TBD became separated from its mates and eventually ditched near the southern shore of Guadalcanal when its fuel ran low. As a result of the appearance of Japanese aircraft the third attack wave was preceded by a fighter sweep of four VF-42 F4F-3 Wildcats. Two of the Wildcats engaged three Kamikawa Maru Type Zero observation (F1M2) floatplanes. Despite being surprised by the speed and agility of their opponents the Wildcats claimed three without loss. Two went down and the third was damaged. Confronted by equipment failure, daunting weather conditions en route to Yorktown and some confusion, two Wildcats ended up on a Guadalcanal beach. The pilots were rescued and returned to Yorktown the same day. The TBD crew was rescued later. The Japanese air groups lost five floatplanes and another damaged.

Type Zero reconnaissance seapane in the Solomons

Returning aircrews reported sinking two destroyers and a cargo ship with a light cruiser beached after bomb and torpedo hits. Other ships were claimed damaged to various degrees. As reported it looked like a major victory. Commodore Bates Naval War College Coral Sea analysis casts doubt on whether the expenditure of munitions was justified by the actual results. Destroyer Kikuzuki was beached and later sank but three other ships sunk were modest auxiliary vessels. By the following day six Yokahama Air Group flying boats were flying regular patrol missions on northeast to southwest tracks out 600 nautical miles from Tulagi.

The Air Campaign

By April 1942 Allied intelligence became aware that the Japanese were showing interest in New Caledonia and islands to the east. Some islands had modest air garrisons; others had sparse or no defenses. With the Japanese established in the lower Solomons, that island chain was seen in a new perspective. On a map it might look like a spear slanting down from Rabaul toward the most advanced Allied position in the south Pacific. The Japanese defeat in the Battle of Midway in early June changed calculations. However, soon Allied intelligence discovered that the Japanese had not given up on taking Port Moresby. They merely changed their approach from a seaborne invasion to an overland attack from the north coast of New Guinea. The Japanese postponed Operation FS and by mid-July cancelled it. After Midway, the Allies understood such an effort was extremely unlikely. This made the lower Solomons, Tulagi and Guadalcanal which the Japanese also occupied, the outer rim of their defense perimeter in the area.

After the Battle of the Coral Sea air operations on the Allied side increased reconnaissance and air strikes on Japanese positions in the Solomons. Tulagi was added as a target for both reconnaissance and attack. Reconnaissance and attack missions continued to be flown against Kieta and Buka in the northern Solomons. The central Solomons were also covered by reconnaissance from Port Moresby. The R.A.A.F. squadrons that had used Tulagi as an advanced base had their primary base at Port Moresby. After the Battle of the Coral Sea, intensified Japanese air attacks on Moresby caused Nos. 11 and 20 Squadrons to relocate to Bowen near Townsville on the Australian mainland. It was from Australia that they initiated their first mission against Tulagi. These were small squadrons having a nominal strength of six Catalinas each with fewer operational. They were not the only Catalinas available. Operating from tender U.S.S. Tangier at Noumea, New Caledonia were U.S. Navy PBY-5 Catalinas of VP-14 (six) and VP-71 (twelve). They were later joined by VP-23. An air campaign of sorts started slowly and picked up momentum as Allied offensive plans crystallized.

Navy PBY-5A Catalina

Four Catalinas deployed from Australia to Noumea on 28 May for action the following day. The first strike on Tulagi involved both Australian (11 and 20 Squadron) Catalinas and three U.S. Navy Catalinas from VP-71. Also on the 29th an LB-30 from Port Moresby flew a reconnaissance over Tulagi returning with photographs. Refueling from H.M.A.S. Wilcannia in the Belep Archipelago off the northern tip of New Caledonia provided the Catalinas a margin of safety for the long range mission. The strike took place in darkness on 29-30 May. The Aussie Catalinas carried eight 500-lb. bombs and ten 250-lb. bombs. The Navy Catalinas each carried four 500-lb. bombs. The Australian Catalinas arrived at Tulagi first. They reported burning a Japanese flying boat, an AA position silenced, with hits on buildings, wharves and a small vessel. One Catalina returned with a machine gun hit in a wing. As the Navy Catalinas began their bomb run they noticed several bomb explosions and anti-aircraft fire indicating the Australians were over the target at low level. Mission leader Lt. George Meade broke off the attack and made a wide sweep of the area to allow the Aussies to complete their attack without Navy bombs falling on them from above. After circling the area they dropped their bombs from a “V” formation. Like the Australians they noted fires and rising smoke from their attack. The Japanese noted two separate raids and estimated two flying boats were involved in each.

American troops part of future Americal Division arrive in Naw Caledonia March 1942

This otherwise successful mission had a sad conclusion when the Navy Catalinas ran into rough weather on the way home. Dropping to low level their radio direction finders provided little help. Low on fuel eventually all landed in the open ocean. Meade’s PBY landed near Mare Island in the Loyalty Islands north of New Caledonia and eventually drifted on shore and was wrecked. A destroyer was sent to refuel the other two. One PBY took on water and could not be saved. The other (71-P-10) was stripped of excess weight and managed to take off and return to base. No crewmen were hurt.

The Australian Catalinas mounted a follow-up attack on June 1st dropping six 500-lb. bombs, ten 250-lb. bombs and four 68-lb. incendiaries. The first week in June brought a series of reconnaissance missions by B-17s and LB-30s of the 435th Bomb Squadron. As the 88th Reconnaissance Squadron the squadron’s B-17s flew into the chaos of the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. It was sent to the southern Pacific in February 1942 and carried out the first attack on Rabaul. Two name changes (14th and 40th Recon Squadron) were made before 16 May when it finally became the 435th BS attached to the 19th Bomb Group a veteran of the Philippines and Java campaigns. Their B-17s were equipped with locally modified armament, twin .50 caliber machine guns in the nose position. They often flew with Australian co-pilots. On the 4th of June during a reconnaissance mission a B-17 came down from its normal high altitude and damaged a Tulagi floatplane by strafing.

The first Japanese arrived on Guadalcanal on 8 June. They set up a tent camp on the Lunga plain. Later outposts were established at Cape Esperance and other points. Coast watchers on the island took notice of the smoke generated by the Japanese burning off grass on the Lunga flatlands. On 20 June they reported their observation by radio.

During June the initial elements of the 1st Marine Division began their movement to New Zealand. By July they arrived in strength and began training. They were sent there to prepare for an amphibious landing. For planning purposes their invasion target was initially described as “Tulagi and adjacent positions.” On 10 June a reconnaissance mission observed Guadalcanal as well as Tulagi. Three days later photos were taken of Guadalcanal from 20,000 feet through holes in the clouds. Another recco mission followed on the 18th. Information reaching the South Pacific (SOPAC) Command indicated that the Japanese were burning off grass on Lunga plain on the large mountainous island of Guadalcanal about twenty miles south of Tulagi. On 24 June Cdr. Matthais Gardner, Chief of Staff to COMAIRSOPAC Admiral McCain, flew aboard a 435th BS B-17 on a reconnaissance mission over Guadalcanal and Tulagi from Port Moresby. Photographs were taken. In New Guinea an intelligence summary noted “evidence of enemy occupation and some activity in Lunga area” of Guadalcanal.

Rough map available to Gen. Vandegrift mid-July 1942

On 25/26 June Lt. James Johnson led three VP-71 PBYs in a strike against Tulagi. Occupying the co-pilot seat in Johnson’s Catalina was RAdm. John McCain, SOPAC air commander, father of a future commander of the Pacific Fleet and grandfather of a Viet-Nam POW/U.S. Senator/Presidential candidate. One PBY aborted and the other two got to the area in a rainstorm unable to see the target. They dropped eight 500-lb. bombs from 12,000 feet. The Japanese were apparently unaware of their attack or even their presence. On 26/27 June three Australian Catalinas encountered heavy caliber AA fire over Tulagi and Gavutu. Returning from the mission one was attacked by an F4F mistaking its roundel for Japanese markings. On 28/29 June two R.A.A.F. Catalinas attacked Tulagi in poor visibility. An attack by three VP-14 PBYs on 29/30 June dropped twelve 500-lb. bombs on Tulagi. This was followed by an attack by two R.A.A.F. Catalinas. The Japanese reported this attack although details of the damage are unavailable. The Australians carried out strikes with a single Catalina on three of the first four days of July. During the mission on the first 700 machine gun rounds were expended in addition to 250-lb. bombs and small incendiaries.

On the first of July the aircraft transport Mogamigawa Maru, cargo ship Kinryu Maru and destroyer Akikaze arrived off Lunga Point. The lead elements of security troops and construction personnel of the 13th Construction Battalion (Setsueitai) landed. Their mission was a preliminary to Operation SN the construction of an airfield for land based aircraft. An additional labor force and construction equipment was on its way to Guadalcanal.

On July 2nd the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff directive on operations in the Pacific was issued. The overall objective was to conduct offensive operations to deprive the Japanese of the New Britain – New Guinea – New Ireland area. The initial task specified was to occupy “the Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagi, and adjacent positions.” The initial planning date for the already anticipated operation was 1 August. Soon the Santa Cruz Islands were dropped as an objective and later the key “adjacent position” was identified as Guadalcanal.

Meanwhile the Japanese were deeply involved with preparation for their overland campaign against Port Moresby. The cast of characters for the intensification of the “air campaign” over the Solomons was evolving. Japanese medium bomber losses in the Battle of the Coral Sea were significant and part of the 4th Air Group was sent to Tinian to reequip and train. The Genzan Air Group returned to its parent Air Flotilla in the Marshall Islands early in July. An influx of Zero fighters kept up pressure on Port Moresby supplemented by small bomber raids. On the Salamaua and Buna fronts Japanese floatplanes carried out reconnaissance and strafing attacks. To supplement the Yokohama Air Group a dozen Type 2 fighter floatplanes model 12 (A6M2-N) were air ferried from Japan early in June (Lt. Riichiro Sato commanding). They spent a month flying air defense missions at Rabaul before transferring to Tulagi. Two new Type 2 large flying boats (H8K1) of the 14th Air Group detachment enhanced the long range search and attack capability later in July.

Type 2 fighter seaplan, pilots and maintenance men

On 5 July the fighter floatplanes flew into Tulagi eventually operating from moorings off Haleta on Florida Island. The SN convoy arrived in the lower Solomons on the fourth and began landing troops and equipment on Guadalcanal the following day. In addition to a security detachment of naval ground troops the main strength (less one company each) of the 11th and 13th Pioneer Battalions landed. The Americans estimated the two construction battalions totaled nine hundred troops with an additional 250 landed later. However, each of these units had a strength of more than a thousand personnel. Material and equipment catalogued by the 1st Marine Division campaign report included 4 tractors of various types, 6 heavy powered rollers, 3 powered cement mixers and a welding unit. Vehicles included 60 (1½ or 2-ton) trucks, 5 motor cars and 5 freight motorcycles (likely tricycle type). Tools were mainly hand tools, saws, hammers, picks and shovels. There was 150,000 gallons of low octane gasoline (useable by Japanese trucks), 600 tons of cement, 80 tons of reinforcing bars, 40 tons of 20’ steel girders, 20 tons of steel beams, and miscellaneous lumber, pipe and steel cable. Interesting is the lack of bulldozers and dearth of power tools. Only a fraction of the trucks were serviceable when the Marines landed. Another piece of Japanese equipment the Marines captured on Guadalcanal was an early Japanese radar. It apparently was not functioning in support of aerial defense operations in July and August, however.

It was not just the Japanese that received aerial reinforcement and developed new airbases. In addition to airbases on Fiji and New Caledonia the Americans completed a new airbase on Efate Island and started construction on Espiritu Santo Island six hundred miles from Guadalcanal. The 11th Bomb Group with four squadrons of B-17Es was designated a mobile strike force and ordered to deploy from Hawaii to the southern islands. Two B-26 squadrons flew into New Caledonia and Fiji. Two fighter squadrons on those islands numbered more than fifty P-39D and P-400 Airacobras. Over two dozen PBYs were operational in three Navy squadrons. There were also a few OS2U floatplanes. Marines were represented by VMF-212 with F4F-3 Wildcats and soon to arrive VMO-251 with F4F-3P photo Wildcats. New Zealand provided thirty aircraft including 18 capable Hudson patrol bombers. Additional aircraft were based on more distant islands.

42nd BS B-17E over the U.S. before arriving in Hawaii; note remote control ventral turret

A reconnaissance mission over Guadalcanal on the fifth of July reported that an airfield was under construction. The following day details of the ships gathered offshore were reported as well as jetties to the shore and three or more AA guns but no airplanes. Bombs were dropped. Azuma Maru anchored close to the shoreline was the target of bombs dropped from 3,000 meters. The bombs missed by two hundred meters and no damage was done. Six seaplane fighters scrambled but failed to intercept. On the seventh a Liberator dropped six 500-lb. bombs and claimed to sink a motor vessel. The Japanese reported an attack by a B-17 on a cargo ship with the closest bombs a hundred meters away.

The Japanese had been flying daytime standing patrols with two seaplane fighters with additional fighters scrambling once intruders were sighted. On the tenth the first interception occurred. Two Liberators reported one float fighter left the combat trailing smoke. The Japanese claimed one B-24 after expending a hundred 20mm rounds and 800 7.7mm rounds. Neither bomber was lost but one returned on three engines. On the same day the ground echelon of the 11th Bomb Group left Hawaii on the U.S.S. Argonne bound for New Caledonia via Canton Island in advance of the air echelon. Navy PBYs resumed their nocturnal attacks. On 10/11 July three VP-14 Catalinas returned without bombing due to weather conditions. On the 13th and 16th float fighters were aloft but reconnaissance planes completed their missions without being intercepted. RAdm. McCain authorized daylight attacks. On 14 July six VP-71 Catalinas sortied for that purpose. Perhaps luckily for them they turned back due to bad weather. Experience early in the war had shown PBYs to be vulnerable to daylight interceptions by fighters. On the same day a reconnaissance mission out of Port Moresby reported there were three medium or large motor vessels off Lunga Point.

On 17 July a message to the 25th Air Flotilla sent from Shore Air Base #942 was intercepted and subsequently decoded and translated. It reads:

-

- At 1140 one B-24 type plane attacked RXI [Guadalcanal] and we attacked with 2 naval fighting planes. The enemy disappeared into the clouds while tail spinning (after being attacked more than 7 times) and is believed to have crashed. One of our planes has not returned; and one was hit by a shell [shells]

- One flying boat and 4 naval planes were sent to search for the missing plane. All returned safely later

- Possible 4 naval planes will be used tomorrow.

The returning float fighter reported expending one hundred 20mm and 650 7.7mm rounds. The pilot correctly reported his opponent as a B-17.

At 1320 on the seventeenth B-17E No. 41-2639 of the 435th BS piloted by 1Lt. Robert Ramsey reported engaging and destroying two Zero floatplanes. The combat took place at 9,000 feet. Cpl. James Underwood, side gunner, and Sgt. Edward Van Every, top turret, received victory credits. They expended 800 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition at ranges from 200 to 300 yards.

Flying on this B-17 were Lt. Col. Merrill B. Twining USMC, assistant operations officer of the 1st Marine Division and Maj. William McKean USMC. Photos taken on this mission failed to get to Marine planners in a timely manner due to administrative mishandling. However, observations by the Marine observers provided the important information that no extensive beach defenses were seen in likely landing areas on Guadalcanal. Lt. Col. Twining was the brother of Army Air Force Brig. Gen. Nathan F. Twining who in January 1943 became commanding general of the newly created 13th Air Force in the South Pacific. Later he became to first Air Force officer to be named Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

On 23 and 24 July a sort of changing of the guard took place. On the 23rd three B-17Es of the 11th Bomb Group flew the unit’s first reconnaissance over the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area. The Bomb Group was not well equipped for such a mission and had no personnel with photographic expertise. It was provided with Navy cameras and aided by photographers from VMO-251. On the following day a B-17E of the 435th BS flew a mission to the same area. Thereafter the recent Japanese landing in the Buna area followed by their advance toward Port Moresby would dominate 5th Air Force attention. What missions were flown from New Guinea to the Solomons thereafter would be over the northern and central Solomons that fell with in the Southwest Pacific Area rather than SOPAC territory in the lower Solomons.

Ninety-five army aircraft assigned to SOPAC were formed into a task force to support the landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi. This consisted of thirty-five B-17s of the 11th BG, twenty-seven based on New Caledonia and eight at Nandi, Fiji Islands. The advance base on Espiritu Santo was barely useable for heavy bombers but a B-17 successfully landed there on 28 July. The 69th and 70th BS had ten B-26s on New Caledonia and twelve at Fiji. Thirty-eight P-39s and P-400s of the 67th FS were on New Caledonia. The first reconnaissance mission on July 23rd was followed by another on the 25th. On the same date B-17s began flying search missions. The B-17s complimented and expanded the search work already being done by Navy PBYs. Tulagi was the main base from which the Japanese reciprocated search work. That point was made on 29 July when a Catalina and a Type 97 large flying boat exchanged fire while on searches over the Coral Sea. Both aircraft returned to base.

Admiral McCain tasked Col. LaVerne G. Saunders CO of the 11th BG with maximum effort bombing for one week before the invasion whose date had been revised to 7 August. However, the Catalinas kicked off the bombing campaign. Three VP-23 PBYs were over the area on 29/30 July. The Japanese reported one large enemy aircraft over Guadalcanal and what they assumed was the same aircraft sometime later over Tulagi. At Tulagi fragment damage was inflicted on a large flying boat. At Guadalcanal one bomb exploded near an AA gun killing one sailor and wounding another from the 84th Guard Force. Another bomb wounded two engineers in the billeting area. A truck and a roller were demolished. VP-14 followed up with three Catalinas on 31 July/1 August. Their activities went unrecorded in available Japanese sources.

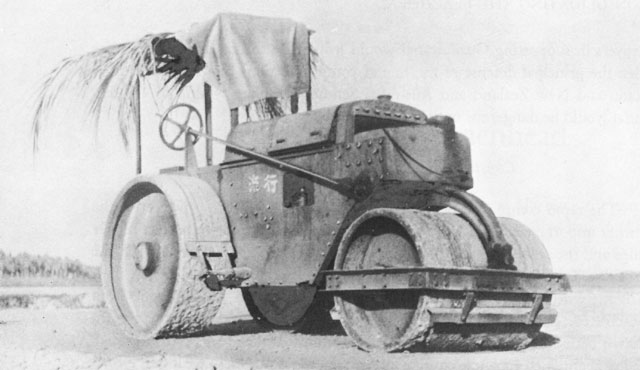

Captured roller used by Americans

Maximum effort for the 11th BG did not mean all thirty-five B17s. Only aircraft with auxiliary fuel tanks in the radio compartment could reach Guadalcanal from Efate. The extra fuel provided a safety margin but also limited the bomb load. Early on 31 July two Fortresses of the 98th BS one with Saunders as an observer and five from the 26th BS flew the first mission. They encountered violent weather and flew most of the way to the target at a harrowing five hundred feet above the waves buffeted by turbulence. As they neared Guadalcanal they climbed and broke out of the soup at 18,000 feet eventually bombing from 14,000 feet. Circling Lunga they dropped 100-lb. and 500-lb. bombs on the airfield through openings in the cloud cover. AA fire was ineffective, and no fighters were encountered. The airfield and supply dumps at Lunga Point were hit. The Japanese scrambled three float fighters but their prey “escaped.” American sources are in conflict as to whether seven or eight B-17s were involved. The Japanese counted seven.

Captured airfield; note bomb craters from US attacks

The eight B-17s that were to be involved on the first mission plus two more from the 431st BS mounted the second mission on the first of August. Tanks were topped off at Efate outbound and the planes refueled at the rough field at Espiritu Santo on return. This permitted an increase in bomb load. The target was the Tulagi seaplane base. Forty-two 300-lb. bombs fell on barracks and other buildings and a four-engine flying boat was claimed destroyed. Some 500-lb. bombs were dropped on targets at Guadalcanal. Japanese accounts state seven bombers attacked Tulagi and three Guadalcanal. Six float fighters intercepted. B-17 gunners claimed two kills. Two fighters were hit by their fire but returned to base. The sea fighters claimed to have inflicted severe damage on three bombers none of which was claimed destroyed; all the American planes returned to base. The Japanese reported two flying boats and two intercepting fighters damaged but repairable. At Tulagi three casualties were inflicted, one fatal. Some buildings were damaged. At Guadalcanal bombs fell near the wharfs and airfield without causing damage or casualties.

On the second only six bombers from the 26th and 98th BS made the trip north after a series of accidents grounded four B-17s. A Japanese report has ten bombers over Guadalcanal and one at Tulagi. Twenty-one 500-lb. bombs and fourteen 300-lb. bombs blanketed the runway and hit two hangers per American reports. The Japanese put up twelve fighters during the day. They expended 1,150 20mm and 2,200 7.7mm rounds claiming two B-17s, one certain and one uncertain, shot down and two others severely damaged. One B-17 had an engine shot out and was severely damaged but returned to base. Two of the float fighters were damaged in combat and one undergoing repair was also damaged. All were repairable.

Only two B-17s were over Tulagi the following day. Other crew members were rested. Malaria and malaria prophylaxis were debilitating many crews. Capt. Jack Thornhill and 1Lt. Hugh Owens dropped down to 6,000 feet to unload twenty-eight 300-lb. bombs. Barracks and houses were destroyed. The Japanese unsuccessfully scrambled three fighters.

On the fourth successive flights of three B-17s attacked Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The Japanese counted nine in total and scrambled six fighters which intercepted the first flight of three from the 26th BS. The fighters assailed the bombers in closely pressed firing passes. One fighter was claimed shot down, but the others kept up the attack for an extended period. A stricken fighter crashed into B-17E No. 41-9216 piloted by 1Lt. Rush McDonald and both aircraft fell into the sea in flames, the only loss from each side.

On the fifth the Japanese put up nine fighters to counter a reported five B-17s claiming two seriously damaged. Ten B-17s were over the area according to American reports with all returning to base. One hundred pound and 300-lb. bombs started fires in the stores area of Kukum landing. Lunga airfield was hit with 500-lb. bombs. One intercepting Japanese fighter was hit but repairable.

Bad weather and a broken refueling pump bedeviled American efforts to carry out strikes on the sixth the day before the Marine landings. Few airplanes got off and the Japanese reported all clear on patrols over Guadalcanal and Tulagi. However, bad weather also thwarted Japanese search efforts as the invasion task forces closed in on Guadalcanal. Searchers from Tulagi that would have discovered the advancing Allied ships in good weather either overflew them without sighting them or cut short their searches before encountering them. As dawn broke on August seventh American ships arrived unmolested off Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

Invasion forces arrive unmolested

On the seventh the 11th BG flew only search missions and one B-17 failed to return. In the weeklong “all out” bombing effort only one B-17 was lost in combat. Another was lost in a crash landing after a mission and one in a ground accident before a mission. Four Japanese floatplanes and three pilots were lost in July’s defense effort. The commitment of modest resources by each side yielded modest results, especially disappointing for the Japanese. The first Solomons air campaign was over. The Guadalcanal campaign had begun…